Postcard from Korea photo essay | By Stephen Wunrow (Spring 2020 issue)

Six years after the Sewol ferry sank off the southwestern coast of South Korea on its way to Jeju Island, there were various tributes in South Korea to the tragedy, including the release of a new documentary film which inquires into the causes of the accident.

The ship was raised in March 2017 and towed to the port of Mokpo, where it has been since then while investigators sift through the debris on board. Of the 304 who died, the bodies of five of the victims are still unaccounted for.

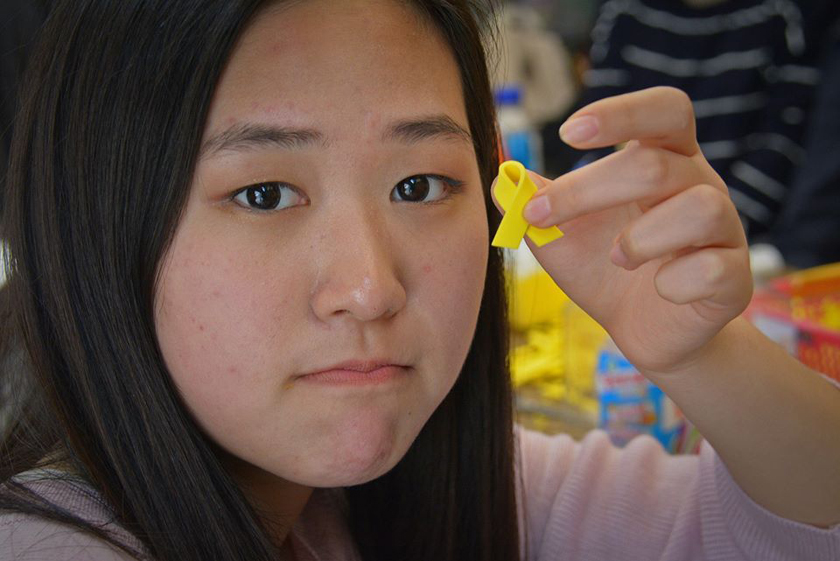

The symbol of the Sewol disaster became a yellow ribbon, which are seen streaming from the wire fences at Mokpo and on all the protest literature and items that were developed over the six-year campaign to restore justice to the victims and their families.

More than 250 of the victims were high school students and their teachers from Danwon High School in Ansan on their spring vacation trip. The crew failed to evacuate passengers from the ship; they were told to stay below decks while the ship turned onto its side, then upside down, trapping the passengers aboard.

The disaster has been the subject of several films. The most recent documentary account, Ghost Ship (directed by Ji-yeong Kim, with journalist Eo-jun Kim) was released just prior to the April 14, 2020 anniversary of the sinking.

While passengers were left to their fate, the captain and crew escaped from the ship. Captain Jun-seok Lee was later sentenced to life in prison for criminal negligence, and 14 crew members received sentences of between 18 months and 12 years. Dozens of ferry company officials, safety inspectors and Coast Guard officials were convicted on various criminal charges related to the sinking.

This accident is more than a simple maritime tragedy because of the many unanswered questions about why the accident happened and why the government was slow to respond in rescuing the ship, in raising the ship (which took three years, and in investigating the sinking afterwards.

Charges to the ferry company and commercial regulators included allowing alterations to the vessel that replaced some of the weight of ballast at the bottom of the ship with additional cabins to accommodate more passengers and cargo higher up in the ship, making the ship too top-heavy for the deep water shipping area in which it traveled.

Charges of government negligence in its failure to oversee the ferry industry regulation was a factor in the ouster of President Geun-hye Park, who was forced from office through a peaceful people’s campaign in South Korea, dubbed the Candlelight Revolution, which involved nightly demonstrations over the course of many weeks in late 2016 and early 2017.

Korean Quarterly is dedicated to producing quality non-profit independent journalism rooted in the Korean American community. Please support us by subscribing, donating, or making a purchase through our store.