Story of Princess Deokhye would be better served by telling the truth | Film Review by Bo Brown (Summer 2019 issue)

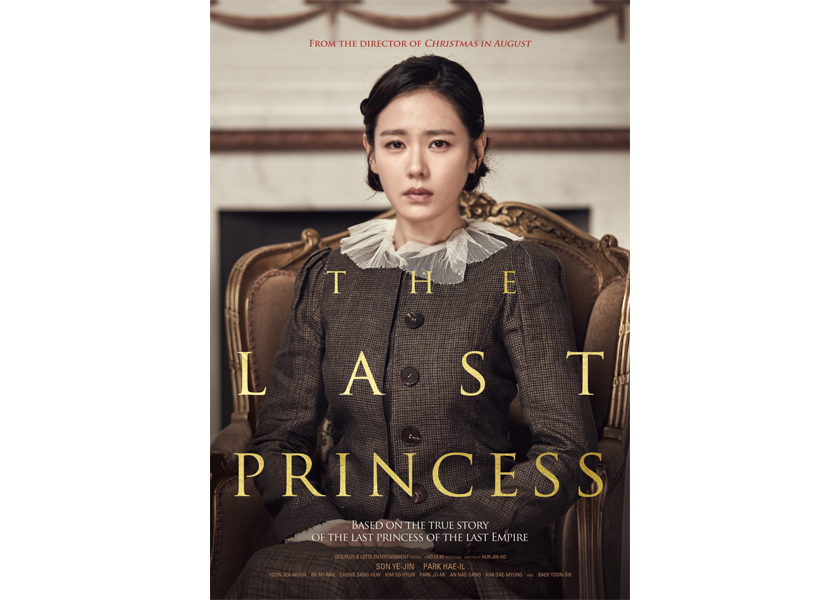

The Last Princess, Directed by Jin-ho Hur (2016)

Considering that Deokhye Yi was the last princess of the Joseon Dynasty, a political empire that lasted for over 500 years, it is odd her story was not well known — even in Korea — until fairly recently. Other than a 1996 biography (in Japanese, by a Japanese researcher of women’s histories), she was little more than a footnote until 2010, when Bi-young Kwon wrote an enormously popular novel based on her life entitled Princess Deokhye.

Kwon has said she saw a photo of the princess as a young girl, was instantly drawn to her and wanted to remind people about her. In turn, director/screenwriter Jin-ho Hur was intrigued, seeing TV footage of Deokhye’s return to Korea in 1962 when many of her former court ladies gathered at the airport to welcome her back after 40 years. It seems anyone who catches a glimpse of this sad woman wants to tell her story.

This princess’s life does sound like a movie plot: Born to an elderly and doting father (Emperor Gojong), held as a royal hostage for two decades in Japan and virtually forgotten about for another 17 years, she returned to Korea in 1962 to little fanfare. She then lived in the palace where she spent her childhood until her death in 1989, suffering from loneliness and bouts of mental illness that plagued her for most of her life. Her self-appointed biographers have taken some liberties with the details, but as is true for all movies beginning with “based on the life of…,” we must expect a good story, not precise history.

As a movie, The Last Princess is lovely. It is well-written and beautifully shot. The star, Ye-jin Son, is simply excellent in the role, which must have been a difficult one. She apparently spent most of her time struggling to reconcile the historical records about the princess with the role as written. There is no doubt she succeeded in creating a compelling character. Her princess is believable and wonderfully realized.

Director Hur focuses on two things. The first, naturally enough, is the home life of the young princess, both as a child in Korea, and while she lived in Japan. The child Deokhye (portrayed with charming haughtiness by Rin-ah Shin) is clearly beloved and spoiled by her elderly father. The father dies under mysterious circumstances. We really get to know the heroine when she again appears as a spirited young teenager (played by So-hyun Kim) who refuses to cooperate with Japanese attempts to use her. Her popularity with Koreans prompts her downfall. She is sent to Japan to be “educated.” She goes to live with her older brother, who preceded her to Japan as a virtual hostage.

Years pass. We now meet the adult Deokhye, as interpreted by Ye-jin Son. The impression is one of silent, resentful suffering. She is reunited with her one time-fiancé, Jang-han Kim, now serving in the Japanese military. After a rocky start, they begin a sweet, semi-romantic relationship, and she finds a protector. She is in need in protection, but not necessarily from her captors.

The character Jang-han is based on a real person who was engaged to the princess in their youth. He is not completely fictional, but his impact on her life is definitely greatly inflated here. Having said that, as a storytelling and unifying device, the character is well-implemented.

Hae-il Park plays the adult version of Jang-han, and the role covers a period of almost 30 years. Park alternates between depicting the virile, dynamic freedom fighter, and then the elderly news reporter chasing his last aspiration, and he makes a good job of it. Charming, clever and effective as a young soldier, he is equally believable as a tired, crippled and aging man remembering the old days and just trying to do right by his true love.

And so we come to the second focus of Hur’s film, which delves into who is to blame. He does not go the route of many films about foreign occupation. The tone is not blatantly patriotic. He does not simply present a collection of inhumane overlords cruelly crushing the hopes and bodies of their Korean victims for no apparent reason and expect us to feel something. In fact, there are only a few brief appearances of Japanese characters at all. One completely sympathetic character is the Japanese wife of Deokhye’s brother, the Korean crown prince. The focus is on individual people in stressful situations.

The emphasis of blame is on collaboration. The collaborators are Korean businessmen, who here are frankly soulless profiteers. The movie implies that identifying Korea’s outside persecutors is not important. What is important is greed — a desire for power and money. The Japanese provided a mechanism for these Korean parties to take power. One might conclude they would have found another means to do so at some point, but this one was handy. This might be seen as a natural extension of the long-time adversarial relationship between the monarchy and various Korean political interests.

And so, the princess’ most egregious foe is not Japanese. He is a Korean functionary and Japanese lackey, Minister Han (Yoon Je-moon), who bullies and manipulates the royal family. It is not clear whether the character represents a real person, but it does not matter, really. The character stands in for a group of people the director wishes to chastise.

Yoon’s portrayal of Han is gleeful and distasteful in equal measure. In every encounter with the hapless Deokhye, he terrorizes the gentle girl, reveling in finding brutal ways to break her spirit. He is the machine of her downfall. At any sign of her taking her own destiny into her own hands, he crushes her.

As a movie bad guy, Minister Han brings the action together in a close approximation of real-life events. As a character, as is too often true with adversarial characters, he is a bit lacking. His vitriol toward the princess and her family is nearly personal, but it is mysterious. We don’t have any background on him except that he first appears as some kind of guard in the royal court. We don’t know why he idolizes those who overran his country. Perhaps something happened to his family, but we don’t even get a hint of that. Some background on this character would have provided welcome context.

Director Hur is known for romantic films in modern settings about broken people finding love in unusual, sometimes tragic circumstances. There is plenty of that on view here. There is, in addition, subtle and clever storytelling, along with a thoughtfully constructed scenario.

The level of detail is impressive. It may not be obvious to the western viewer, for instance, that the characters slip effortlessly from Japanese to Korean, sometimes from sentence to sentence, depending on the person they are talking with. But to the Korean viewer, it might be a strong reminder that Japan tried to obliterate their culture by so many methods, not the least of which was discontinuing Korean language instruction in Korean schools and replacing it with Japanese.

The sets feel realistic and true to period. The score consists of mostly classical pieces, and as is hopefully the goal for movie music, adds to each scene without distracting from it. The costumes are based on clothing actually worn by the royal family, and the actors wear them well.

In this film, the clothing also provides clues to the action. Minister Han wants Deokhye to wear a kimono (a Japanese formal dress) as a sign of subjugation, but she insists on either modern wear or hanbok (Korean) to thwart him. When Emperor Gojong holds court, he wears traditional robes while his advisers wear formal western wear, as if to say they are looking to the future while Gojong is dragging behind. Gojong would certainly see it in opposite terms. Costuming is a very significant detail in this movie and in the telling of the story of Deokhye.

In the service of storytelling, many truths fall by the wayside. Perhaps the most glaring here is the real-life hero of Deokhye’s escape from Japan. In the early 1960s, reporter Eul-han Kim campaigned for the return of Korea’s remaining royals to their homeland because he thought it was morally wrong to keep them out. Through his efforts, which in the political climate of the times must have involved some danger to himself, the elderly royals were finally returned to their homeland.

This courageous story was sacrificed for a romantic lead and white-horse rider to save the day, and so Jang-han Kim was placed into the hero’s role. This provided closure and a certain amount of synergy, but perhaps evidences a certain lack of imagination in using the source materials. However, the truth may yet be told if the success of Last Princess in fact foretells an interest in examining an aspect of Korean history that has been fairly neglected to date, the last days of the Empire from the point of view of the royal family.

Photos of the real Princess Deokhye as a child reveal quiet self-possession and perhaps an impish glint in her eyes. This is her story, and it is rich and full of pathos. What we deem missing may be debated, but in the end, a movie is entertainment. The Last Princess delivers a solid romance, excellent acting and an engrossing narrative. It is entertaining from start to finish. For those reasons, it is well worth viewing.