Lessons from Korea independence fighters at Seodaemun Prison History hall | By Jennifer Arndt-Johns (Fall 2020 issue)

A window to an era of Korean history during which untold thousands of courageous people, including many women and teenage girls, sacrificed their lives for independence is available at a surprising venue —- the same prison where these activists were imprisoned and died.

The museum is the former Seodaemun Prison, now the Seodaemun Prison History Hall, located in Dongnimun, Seoul. Visiting this place was part of a transformative trip from Minneapolis to South Korea through a circuitous route and with a lot of help from some old and new friends.

In 2017, I traveled to South Korea through the Spiritual Journey program offered through the Korean Adoptee Ministry Center (KAM Center, www.kamcenter.org), located in St. Paul. The trip was accompanied and guided by director Rev. Sung Chul Park. Over the last 20 years, the Spiritual Journey program has provided scholarships to fund adopted Koreans’ visits to South Korea.

The KAM Center maintains partnerships with Presbyterian churches throughout South Korea that help support the travel and accommodations of its recipients. Throughout the curated trip, participants meet and connect with Christian Korean families through homestays in cities including Seoul, Daegu, Jeonju and Busan. Participants explore historical cultural sites, visit adoption agencies and experience the everyday banalities of Korean life —- which for an adopted Korean is anything but banal.

My experience on the journey was nothing short of exceptional, transformative and growth-filled. I have many stories and memories to share. Maybe one day, I will write a book. Now, three years later, one of the memories I recall most vividly was the last day I spent together with my host mother in Seoul before returning to Minneapolis.

The day I visited Seodaemun started off typically when my host mother, who spoke limited English, rallied me in the morning to get ready. Unlike my usual self-directed existence in Minneapolis, during this trip I dutifully followed, doing my best to trust whatever new experience might emerge. My host family was quite committed and motivated to show me the sites they knew, and every day spent together was an adventure.

That day, with the help of Google Translate, I learned we were going on a “field trip.” Once ready, my host mother proclaimed, “Let’s go!” and off we went.

We boarded a bus, transferred to the subway and eventually emerged from the Chongno 3-ga stop onto a relatively quiet street —- by Seoul standards. My stomach grumbled —- we left the house with no breakfast. I followed my host mother as she meandered through an area that became smaller and smaller streets. Then, she ducked into a small door that would be easy to miss —- she definitely knew what she was looking for.

The aroma wafting out of the door caught my attention as I edged in behind her. In a unified chorus, the women working sang out, Oso-osayo! (Come in!). In a space no more than 10×10, six small tables were set. Behind the opposite wall, a group of women were working in an even smaller kitchen space surrounded by giant steaming pots of broth, hand kneading and cutting dough on a floury work table.

My host mother plopped herself down at a table, wiped some beads of sweat from her forehead with a handkerchief, and motioned for me to sit down. Smiling, she proclaimed, “Kalguksu… berry pamous!” (Kalguksu “knife cut noodle soup,” is indeed a very famous dish that some restaurants specialize in). In a matter of minutes, one of the women brought out two steaming bowls of kalguksu and placed them in front of us, along with a fresh pot of kimchi. Masshi-keh-taseyo! (Bon appetit!), she proclaimed and whisked herself back to the kitchen.

After she said a short prayer, my host mother encouraged me to begin eating. Soon we were both slurping up our lunches. The soup was a mild, rich, seafood broth, with small clams and perfectly-prepared noodles. When paired with kimchi, the blend of flavors was pure heaven! We needed no words as we enjoyed our meal together. Comfort food… this was Korean comfort food, something I could not get in Minneapolis.

As my host mother finished her soup, she pointed to the wall across from us. Posted neatly on the wall were newspaper articles praising this tiny restaurant, even an English language account entitled How to Be Happy With a Bowl of Kalguksu. From the article, I learned people have traveled from all over Seoul to Chanyangjip (House of Praise) for 35 years.

We continued to our next destination unknown. Little did I know, I was about to be immersed in a hallowed history of my Korean predecessors. Traversing through the busy city with its tall modern buildings, we finally arrived at a stone perimeter wall enclosing some kind of compound. I had no idea where we were going, but the energy suddenly became palpably heavy. My host mother took my hand and held it as we entered what appeared to be a movie set. But it wasn’t a movie set, it was real. It is a former prison.

Seodaemun Prison History Hall (https://sphh.sscmc.or.kr/eng/#firstPage) is a sprawling museum compound in Seoul’s northwestern corner. Surrounded by high-rise apartment buildings and modern businesses, it is one of the area’s last preserved remnants of South Korea’s turbulent struggles for independence and freedom in the early 1900s. During the Japanese occupation (from roughly 1908 to 1945), the Japanese used the prison to incarcerate, torture and execute activists who opposed their rule. Once Korea became independent, this traumatic energy persisted, because the prison was then used by the Korean dictatorial government to incarcerate democratic activists.

The exhibits detail the historical challenges and hardships the Korean people endured from 1908 through 1987 in order to achieve democracy and self-determination. The compound includes an investigation building, male, female and leper prison buildings, workhouse building, cook house, detention building, exercise yard, execution building, medical unit and an engineering work building.

In 1912, the original prison was 17,000 square feet, but due to the increasing numbers of incarcerated Korean independence activists, the prison was expanded in the 1930s to be 30 times larger. Most of the original buildings have been restored and preserved; a residue of suffering pervades the compound, even today. It is a solemn place.

The former investigation building is now the main museum exhibition hall. The exhibits chronicle Korea’s struggles with imperialism, including from France, the U.S. and Japan, beginning in the late 1800s. Korea was officially colonized by Japan between 1910-1945. Exhibits explain the history of the original prison and the fact that generals and soldiers from Korea’s “Righteous Army” of the Joseon dynasty died in the prison.

The exhibits also tell the stories of prisoners who participated in the national resistance. Three of the halls document resistance events that took place through time, and give a brief history of the provisional government in exile that the Korean leadership set up in Shanghai, China in April 1919, after the March First Independence Movement. The museum also details the country’s major democratic movements of more recent times.

Before departing the building, visitors have the opportunity to witness the torture basement. That exhibit details some of the most atrocious, inhumane acts and war crimes committed by the Japanese against Koreans. It would be an understatement to express that this was a space where respect for humanity ceased to exist.

Emerging from the basement into the daylight, visitors are then free to explore the rest of the compound and get a glimpse into what it was like to be an inmate in Seodaemun Prison.

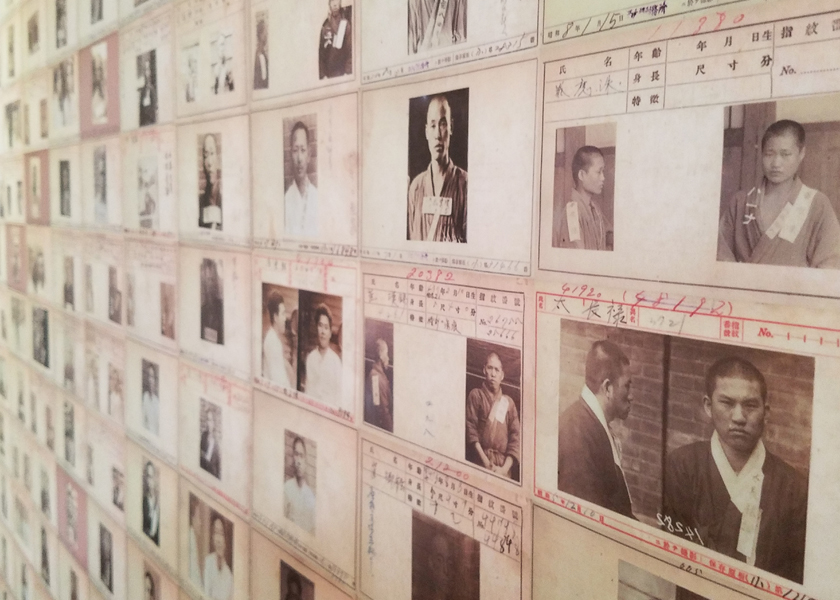

As I explored the grounds with my host mother, I gravitated towards two exhibits. One was a memorial room, dedicated to activists who gave their lives for national independence. The room is an empty space, the walls papered with thousands of faces on cards which are copies of the original inmate cards. Each one details the inmate’s age, address, height and other personal information. Apparently, the National Institute of Korean History has about 5,000 original inmate cards archived. It struck me how these were ordinary people. Men, women, old, young —- some looking too young to do anything wrong. They had in common that they all fought for independence and peace in their country.

As a Korean American, raised in the U.S. with a presumed right to freedom and independence, it is hard to fathom the depth of passion these individuals felt, expressed and ultimately died for. It is a reminder of how easy it is to take for granted, something so valuable. I wondered, “How I could properly honor their memory and sacrifices?”

The next exhibit was located in the former women’s prison used during the Japanese occupation (1910-1945). The exhibit featured the stories of girls and women incarcerated there who had devoted themselves to the Korean independence movement. Once again, they were ordinary people; students, nurses, farmers, laborers, missionaries, who were grandmothers, mothers, daughters and sisters.

One of the most notorious (to the Japanese) and heroic (to Koreans) was activist Gwan-sun Yu who was only 16 when she was detained in Seodaemun Prison for her leadership in the March First Independence Movement in 1919. The exhibit lists the names and home cities of her cellmates in Prison Cell #8. These women and many others fought for their country despite the wrath of double discrimination by their oppressors: Ethnic discrimination as Koreans and gender discrimination as females.

In the records, it stated that even after they were imprisoned, these girls and women continued to resist the Japanese prison authorities, up until their deaths. As I read their histories, my heart ached, as my mind processed the sadness into rage for the suffering they endured. Once again, I wondered, “How could I properly honor their memory and sacrifices?”

Prior to departing the women’s prison building, visitors are routed to a multi-dimensional mirrored room featuring historical photos of women and girls, seemingly suspended in space and time. It is a haunting exhibit that invites visitors to connect with individuals from the past, as each person sees their own reflection in the mirrors along with reflected faces from the past.

The answer to my question emerges in my conscience while viewing this exhibit, “Our memory is honored through your acknowledgement of our lives and an understanding and respect for how we are inextricably connected. Do not take this history for granted, as the only thing that separates you from us, is time.” With my own reflection staring back at me, I saw myself for the first time through new eyes.

That evening, we had a farewell dinner with the elders from the church and our host families. Elder Kim inquired about how we spent our last day, and I explained our meal at the famous kalguksu place followed by our visit to the Seodaemun Prison History Hall. His expression indicated surprise and maybe even some concern. Before he could say a word, I interjected that I highly recommended adding the Seodaemun Prison History Hall to the itinerary for future journeyers.

He seemed relieved as he quietly collected his thoughts, “Yes, I think you may be right. It is painful history that even some young Koreans do not understand.” I expressed to him that as an adopted Korean, it educated me about the struggle “my people” endured and instilled within me a new and deep appreciation for the strength, devotion and resilience of the Korean people.

Seodaemun Prison History Hall covers a time span of just over 112 years. It demonstrates how the people of Korea have overcome and persisted through unspeakable tragedies. I discovered there that my freedom has come at a cost of innumerable lives, only some of them known today. Until my visit to Seodaemun Prison History Hall, I had no knowledge or understanding of that history. Like many of the details of my own personal adoption history, it was an unknown history to me.

Yet, unlike my adoption history, this history has been documented, preserved and made public, so that people can easily understand the sacrifices and efforts that were made for generations in order for South Korea to emerge as an independent democracy. My host mother and her elder family members would have witnessed a piece of this history. I was grateful she introduced it to me, so that I could begin to contemplate the collective struggle of all Koreans, including some of my forebears.

I have always benefited from the freedoms transferred to me as an American citizen. I know that in our country too, each of those freedoms has come at a tremendous cost of countless other individuals who suffered, sacrificed and persevered before me. Like Korean history, American history is also fraught with tragedies where freedoms are won at the cost of others’ lives. While our country has made progress, we are challenged with achieving equity for all.

The history of Seodaemun Prison is not just relevant for Koreans. At a time in our American history when our president publicly encourages divisiveness, blatantly violates his seat of power, refuses to condemn the actions of white supremacist groups who fuel fear, intolerance, hate and violence, Seodaemun Prison’s solemn lessons are certainly relevant at this moment in modern day America.

Like many things in life, freedom and peace can easily be taken for granted when it is all that we have known. With their constant presence, we can easily forget the sacrifices that made these conditions possible. We can neglect to nurture the energy needed to ensure they thrive.

As I witnessed in Seodaemun Prison History Hall, when peace, democracy and freedom is under siege, I must stand up, speak up and revere the fragile sanctity of democracy and the freedoms it affords its citizens in the U.S. and South Korea, or anywhere else in the world.