Filmmaker Joseph Juhn documents a Korean Cuban hero | By Martha Vickery (Summer 2019 issue)

Excited about the seeing the sights and sounds of Cuba for the first time, Joseph Juhn went to Cuba with an adventurous vacation in mind, but the experience soon became much more than a vacation. It started with a fateful meeting, and then rocketed his life in a whole new direction.

Juhn, who at that time had made several documentary short films, took a GoPro camera for fun, and planned to write a blog. The GoPro is a tiny, tough video camera used for personal video; it is often mounted on a helmet or handlebars to film athletic feats from the athlete’s perspective.

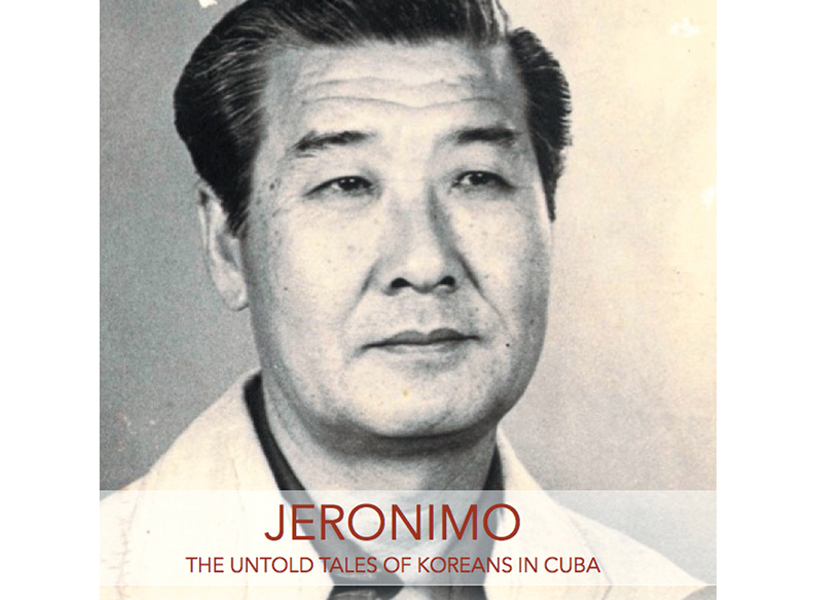

The cabdriver who picked him up was Patricia Lim. In his film Jeronimo (pronounced ‘Heronimo’ in Spanish), Juhn captures his initial conversations with Patricia, during which both express surprise at meeting a fellow Korean, and Patricia explains that her grandfather, Jeronimo Lim, was in the Cuban revolution (1953-59), and was later appointed to Castro’s government, where he achieved the position of vice-minister, second-in-line to Fidel Castro.

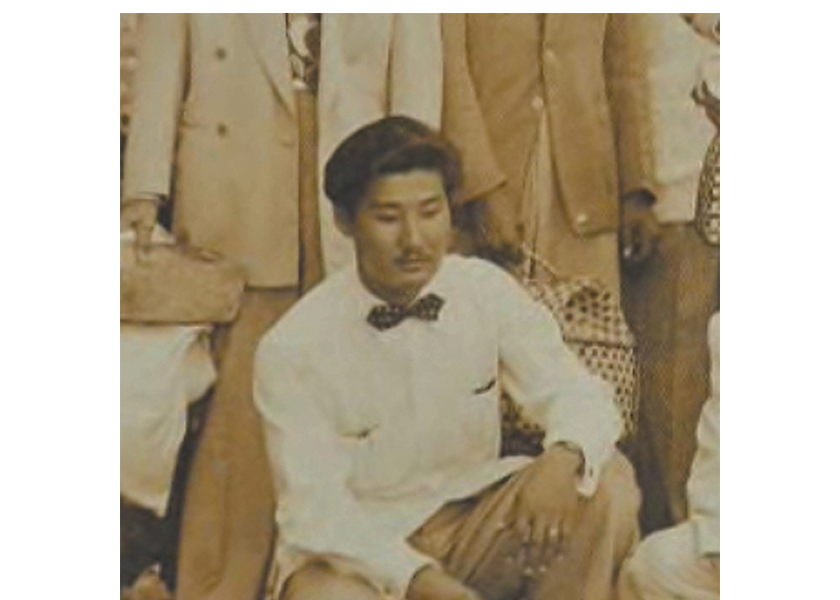

Patricia enthusiastically invites Juhn to meet her grandmother Cristina, Jeronimo Lim’s widow (age 87) who showed mementoes and photos of the couple. He learns another astounding piece of information, that Jeronimo’s father, Cheon Taek Lim, had been a fighter in the Independence Movement in Korea (which began in 1919), and later immigrated with a group of 1,000-plus Koreans to Mexico, where he was forced into indentured servitude in the Mexican henequen fields (a type of fibrous cactus which was used for rope-making). The film explains that he continued to raise funds for Independence Movement fighters in Korea and China throughout the Japanese occupation.

Juhn was born in Minnesota, but spent most of his childhood in Korea, returning to the U.S. for college, graduate school, and a law career. For many years, he has been fascinated with the far-flung Korean diaspora. He has run into other Koreans in many places, and several of his film projects have been about diaspora and identity. He notably helped to film and produce a documentary about Korean adoptee musician and rapper Dan Matthews, and his experiences after his birth parents in Korea contacted him, and told him he had an identical twin brother (akaDAN, 2014).

The fact that Juhn had the mini-camera helped the filmmaker to record the “serendipitous nature” of this chance meeting with Patricia, almost from the moment it happened.

“In the beginning,” he said, I had no knowledge of where this was going to take me, or if it was going to go anywhere at all. It was just a profoundly moving experience.” His blog got a surprisingly large amount of support, and his instincts told him he might be onto something.

After meeting Patricia and her grandmother Cristina Kim, Juhn went on to a fun backpacking trip where he watched sunsets, drank mojitos, smoked cigars, and learned more about the Cuban revolutionaries Fidel Castro, Che Guevara and Jose Marti.

But back in New York, the Jeronimo Lim story continued to haunt him. Juhn researched more about Lim’s leadership of the government and the Korean Cuban community. There wasn’t much history available in English, Juhn said, and it began to dawn on him that he might be uncovering an unknown story of a Korean diaspora hero.

Seven months after his return from Cuba, Juhn set off for Cuba again, this time with a small film crew. He had no idea where the film would take him even then, he said, “because the only solid information I had was that there was this Korean Cuban guy who played an important role in the revolution and then became the vice-minister.” The idea that sparked his imagination was “that an indentured servant grandfather was an independence fighter, and his son was a Cuban revolutionary. …that in itself, creates a compelling enough story,” Juhn said.

After several years of research and filming, and more than a year of editing, Juhn looks back and reflects that “I initially thought this would be a 20- or 30-minute feature video of my cool experience!” Even after returning from Cuba with his film crew, he said, he still thought it was going to be a documentary short.

Back home again, Juhn felt the pull of that history. His second trip to Cuba brought up more unanswered questions about Jeronimo. “From that point on, I started going around and interviewing everyone who crossed paths with Jeronimo, whether they were in Canada or across the U.S., or even Korea, because he went to Korea two times. I wanted to hear anything meaningful, whether positive or ambiguous.”

His research stretched over more than two years and revealed a story that begins with the young revolutionary Jeronimo and follows his life with photos, video footage, and interviews with eyewitnesses. It describes his career as a Castro government insider and concludes with him being a dedicated Korean community leader, working tirelessly as a volunteer to better the lives of fellow Korean Cubans.

Lim also had a very large and talented family, many of whom were leaders in their own right. Juhn said the Lims are like “the Korean Kennedys of Cuba” in the way their name keeps coming up in many areas of Cuban society. The film goes into some of their stories, and explores the Korean Cuban people and their efforts to keep alive their Korean heritage.

Juhn said there are far more accounts about Jeronimo written in Korean compared with English. Lim visited Korea in 1995 and 2003, “and one of his commitments in going back was to try to reconstruct an idea of a Korean identity,” Juhn said. Lim was celebrated as a leader in South Korea, and the cause of Korean Cubans got some press in Korea because of his visits.

Jeronimo is also interesting in that he is a second-generation Korean Cuban, and like many second generation people, he concentrated on improving life for his own diaspora, not in connecting with Korea, Juhn explained. “He was primarily concerned with injustices, poverty and struggles of Korean Cubans,” Juhn said, “and he tried to alleviate the poverty, misery and discrimination he saw in the community.”

That objective may have propelled Jeronimo into being a revolutionary, “because he really believed he had a duty as a Cuban citizen to make a change.” However, Juhn concentrates more on the end of Jeronimo’s long career, especially in the period of the late ‘80s and its aftermath. “It was a time when Communism was falling apart globally,” Juhn explained, “and this was a time when Cuba went through a very special period [of economic hardship] and at the same time North Korea was having a famine,” which was later referred to as “the Arduous March” by Koreans. Simultaneously, South Korea was steadily becoming an economic superpower, he added.

Cubans, whether due to sanctions or food distribution systems failure, were in dire need of materials and food at that time, Juhn said, and Lim keenly felt their suffering. The party line in Cuba was to blame the U.S. for the shortages. However, during this time, the observant Lim began to see many faults in the government he had fought and worked for his whole career. “I think that, partly, that is what Jeronimo is turned off by —- just the rigidity and the dictatorship and the holding onto power by Fidel Castro and the enclave,” Juhn explained.

At least three reliable sources told Juhn that “Jeronimo regretted a lot that he participated in the revolution. He never realized the revolution would beget such consequences as starvation and dictatorship.” Interestingly, Jeronimo’s widow Cristina, protests that “Jeronimo was a revolutionary to the end!” when he asks her about the statements by witnesses that Jeronimo recanted his revolutionary ways.

This is a central tension emerging toward the end of the film. “This is where I also have to question the ethics behind filmmaking, and to which extent I want to expose or reveal the depths of each character,” Juhn reflected. “Cristina is a very complex character herself. But then I wanted to pay tribute to the well-being of the family, and to prevent further judgment that might befall someone like Cristina.”

Cristina is “a hard-core communist and believes in the socialist ideals and that communism will ultimately prevail over anything else. Hence her firm belief and conviction about Jeronimo, that it is impossible for him to have converted, either religiously or ideologically.” There is also some evidence that Lim became a Christian in his later years, an idea that his widow also firmly rejects.

Juhn stops short of drawing a conclusion about Jeronimo’s ideals at the end of his life. However, the Jeronimo’s willingness to consider diametrically different ideas than the ones that lighted his passions as a young revolutionary makes him an approachable historical character. “It is that humility that I became so fascinated with,” Juhn said. “For any communist, after having worked for the government for 50 years, to fully admit that yes, I made a mistake. Yes, that was a poor choice. I mean, it shows character.”

Juhn readily states that Jeronimo is his “first and last” full-length documentary film. He has struggled with many aspects of telling the story, and has been at the editing for about 14 months, after first hiring a professional editor for supposedly two or three months of work. “For 11 straight months, every day, six days a week, we were working eight to nine hours a day. It was really crazy and I lost my health during the process,” he said.

However, it was during the editing process that the story came together. In doing so, ancillary stories of three Lim descendants Juhn followed had to be dropped from the film. One is a Korean Cuban teenager the team followed to Korea when she auditioned to be a K-pop singer. Juhn is editing that footage into its own documentary short.

That a film has to come to an end is the most difficult, Juhn said. “The fact that there is a finite form” and that a film must be a “fixed medium at one point,” is both the goal and the problem to Juhn.

The New York premiere was July 30 2019. Later that summer, the film was modified for a KBS (Korean network) broadcast that aired August 15, celebrated as a commemoration of the end of World War II and the Japanese occupation. Another major South Korean network, SBS, wants to fly the filmmaker to Cuba, where he will visit some significant Korean Cuban sites and discuss his research into Jeronimo Lim’s life and legacy.

The film was also screened at Asian film festivals in Dallas, San Diego, and New York; it was also accepted for the Seoul International Film Festival. The film was also scheduled for private screenings at several Korean organizations, and at the University of Miami’s Cuba Studies program. Later in the year, the film also had a theatrical release in 50 to 150 South Korean theaters later last year.

Juhn will say, with great resolve, that this film is his first and last feature-length documentary film. “If I was to summarize the three years into a few key words, the beginning was passion, but the latter half was just grit. And a sense of responsibility I guess.” For a short time, he was a career filmmaker, and will be in the near future as he travels with the film as it is screened. But he cannot see himself doing it again. “It was my passion project.”

Of the many screenings the filmmaker did, including one in Cuba, with Jeronimo Lim’s widow, siblings and other family members, that showed them how their patriarch’s story will be spread to audiences beyond their island nation.

A trailer for the film is at Jeronimo The Movie, and screening dates will be posted there when available.

Korean Quarterly is dedicated to producing quality non-profit independent journalism rooted in the Korean American community. Please support us by subscribing, donating, or making a purchase through our store.