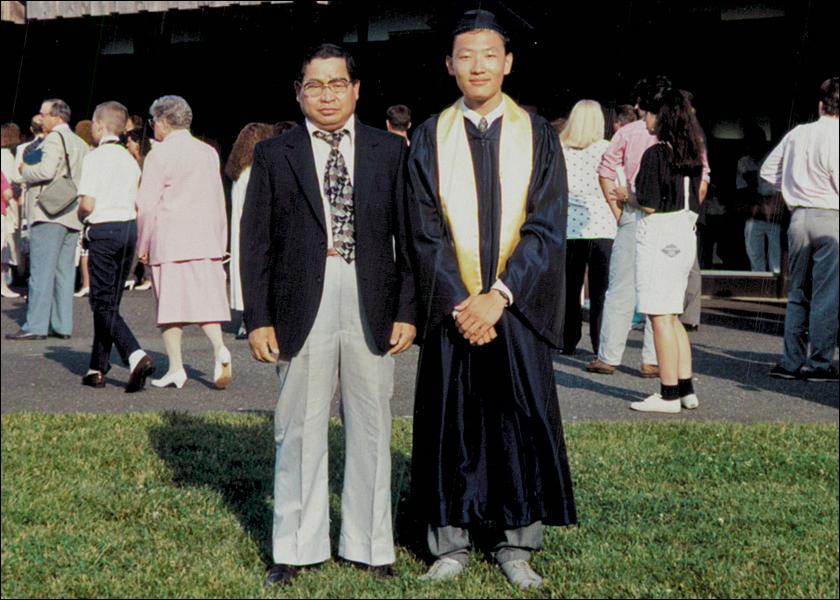

One son’s homage to a unique inheritance from his father | By Sung J. Woo (Spring 2023)

When my father passed away in the summer of 2004, it surprised no one. He’d been sick with kidney disease for years, and frankly, if there was a surprise, it was that he held on for as long as he had. Initially when the diagnosis came down, his nephrologist predicted at best two years, but Dad ended up living with home dialysis for more than a decade.

If I were to calculate my father’s life strictly on financial terms, it wouldn’t be inaccurate to say that he died a failure. It’s a limited way of assessing a person’s value, but that very word – value – often, it speaks of money, and I admit, shamefully, that I’ve listened to its callow calls.

But then there are days when I choose a wider view, of the mountain peak he ascended in his prime instead of the downward slope of his elder days. In my home office I have a photo of my father shaking the hand of Chung-hee Park, the third president of South Korea, in celebration of the success of his import-export business. How many people can say they met the president of their country, let alone got an award from him? Certainly not me.

Anyway, Dad has been on my mind lately because of an object he left me, which I’ve been using with great regularity. Though it was never formally bestowed upon me as such, technically, it is my inheritance: A tripod.

Looking at this powder-black stand with its grippy knobs and quick-release clamps, you might think Dad was a shutterbug and, I, too followed in his love of photography, but neither is true. I can’t remember a single instance of him using a camera, and even though I do enjoy taking pictures every now and then, I don’t use the tripod for its intended purpose. Instead, I use it to hold an iPhone for an app that records and critiques my tennis game.

How did this tripod come into our household? For that, we need to go back to the mid-80s, when it had been part of a bundled purchase, a purchase that never should have been made in the first place.

The glossy advertisement arrived in the mail from American Express, for its esteemed members – the people who never left home without it. The only reason my parents qualified as cardholders was because they owned an oriental gift shop that accepted Amex cards, a by-product of subscribing to their merchant services. And it was only my mother who qualified, as my father at the time had no credit history. Unlike the rest of our family, who came legally through my mother’s brother, Dad had fled South Korea after his business went bankrupt.

He may have been able to dodge his creditors, but he couldn’t outrun his poor health. By the time the colorful Amex catalog popped up in our mailbox, he was already on peritoneal dialysis (PD) due to his non-functional kidneys, an affliction that developed due to his congenital hypertension, which itself wasn’t helped by his heavy drinking during his big business days back in Korea. This treatment type (PD) is a life-changing event, akin to wearing a colostomy bag. Even though he gained the convenience of filtering his blood at home, he also became chained to the daily process. A permanent catheter was installed into his belly, and his stomach lining and a sterile sugar solution performed the duties of a kidney. The half-gallon PD solution was drained and refilled four times a day, which increased to five when its effectiveness waned, which it inevitably did. PD is not a cure; it is merely a way to buy time.

Almost four decades have now passed since the catalog’s arrival, but I can still remember my father showing it to me and asking for my opinion of the products. That’s what it was, not a straight-up “what-can-I-get-for-you” interrogation but a sideways inquiry, which made me feel more grown up than I actually was. Printed on a rich stock of glossy paper, it was nowhere as giant as the old Sears catalogs but a legitimate booklet with a spine. So many items were well over a thousand dollars, which both frightened and thrilled me. Our gift store was not doing well in the sales department – it never did, ever – so merely gazing at these overpriced wares felt off-limits. And yet I desired them, maybe because I knew there was no way we could afford such riches.

When the three boxes arrived from the American Express Company weeks later, everyone was shocked – everyone, that is, but my father, since he’d ordered them. Even though he had lived in America for more than 10 years, he still struggled with English, so I could only imagine how difficult it had been for him to call that 1-800 number and muddle through to make the purchase. But he had persevered, and now here they were, his treasures bought on credit.

The first box was outsized, only slightly shorter than my 12-year-old self and three times as wide. What emerged after prying open the heavy corrugated cardboard was a stationary bike, its metal frame bronzed like a healthy suntan. The only required assembly was screwing in the handlebars and the pedals, and now here it stood, next to the cracked balcony window of our apartment.

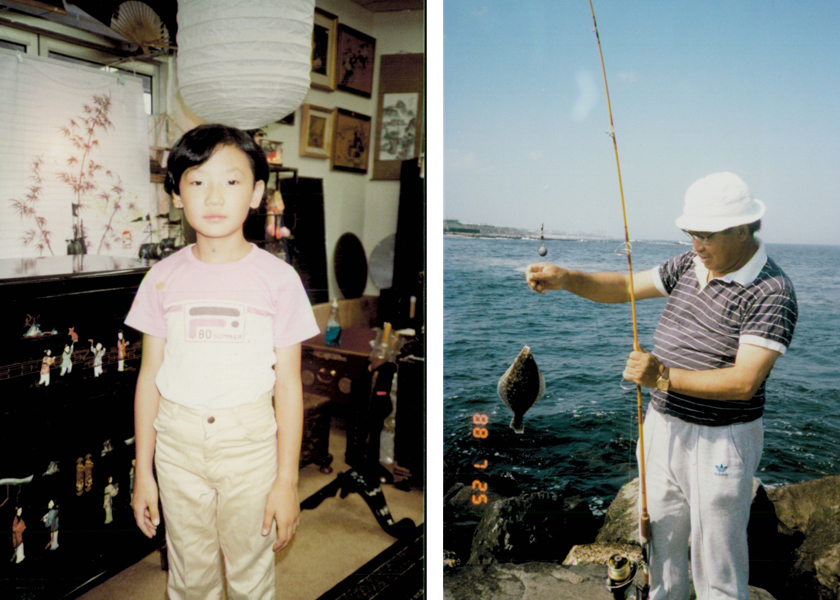

My mother and two older sisters were left speechless and so was I. There were only two sports in my father’s world, and I considered neither of them to be actual sports, even if they both showed up on ESPN from time to time: Golf and fishing. Had I ever witnessed Dad breathe hard from any form of cardiovascular activity? Nope. Imagining him balanced on the tiny seat, pedaling away – no. Never.

Vanity – could that explain it? It’s a well-known fact that PD can result in weight gain, since the solution is sugar-based. Not only did my father gradually add to his waistline, when the solution had just been emptied into his stomach cavity, his belly looked as swollen as that of a pregnant woman. Was that why he’d ordered the exercise bike? Perhaps his manhood was under assault and this was a desperate ploy.

I don’t think so. More likely is that for some strange and unknown reason, I’d fingered the bike as something we should get. Honestly, I can’t remember, and similarly, I can’t recall if I’d suggested the second item, either. Regardless, it was easy to deduce what the second brown rectangular box contained, as the long white box leaning next to it was straight from the manufacturer and embossed on its side were the words “SLIK 50” and a line drawing of the tripod in its fully-extended glory.

My father had purchased the Canon T50 SLR bundle, which came with not only a portrait lens but also a lengthy zoom that was heavier than the camera body itself, plus a wide angle. Blower brush, lens cloth, cleaning solution, a fancy gray and black bag with a bevy of zippered compartments to hold them all – this was a kit befitting a professional photographer.

Dad never got on the bike. Dad never touched the camera. So why had he dropped more than a thousand dollars on things he never really wanted? He was never a spendthrift, so a purchase of this magnitude was an extraordinary occurrence.

Perhaps it was an expression of a midlife crisis, or more accurately, a health crisis. Dad wasn’t the talkative type, so I rarely knew what was on his mind, but if I were to psychoanalyze the purchase of the bike and the camera, I could interpret them as manifestations of opposing forces: The bike as wish fulfillment, a way to gain strength over a failing body, the camera as a memorializing device, to capture his remaining days in the best possible light.

Or maybe the answer is even simpler: A father wanting to buy exorbitant gifts for his only son, even if he couldn’t afford them, because for a brief moment, he could, thanks to a shiny green American Express card bearing my mother’s name. A gift nice enough, expensive enough, to perhaps even be a genuine inheritance.

Sadly, I’m not sure what happened to the bike. Like most home exercise equipment, it wasn’t long until it served as a coat rack. When Mom moved out of their apartment after Dad passed away, it was probably abandoned with the rest of the unwanted furniture. The camera survived, but I sold it on eBay years later; the automatic exposure setting had gone awry, so the only way to operate it was in full manual mode, which was beyond my level of photographic comprehension.

But the tripod? I still have it. And I still use it. According to Merriam-Webster, the word tripod dates back to the 15th century, to describe a vessel resting on three legs. And the word vessel dates back another century, to signify a container for holding something.

This is all in my head, but then again, what isn’t? I know what that something is – it is my father’s unspoken love for me, silently communicated through all of his absent years.

The tripod is light, it’s portable, and it’s from Dad, who, along with the iPhone perched on its head, watches over me as I practice my tennis serve.