K.W. Lee ~ Remembering one journalist’s relentless pursuit of justice | By Martha Vickery (Spring 2025)

There were no “thought leaders” or “change agents” back in the ‘80s and ‘90s, but veteran journalist K.W. Lee was one at a time 30 years before thought leaders were thought of. What is called “advocacy journalism” today was unrecognized by the profession when Lee was deep into it, as far back as the late ‘60s, furiously writing for human rights and social justice causes he believed in.

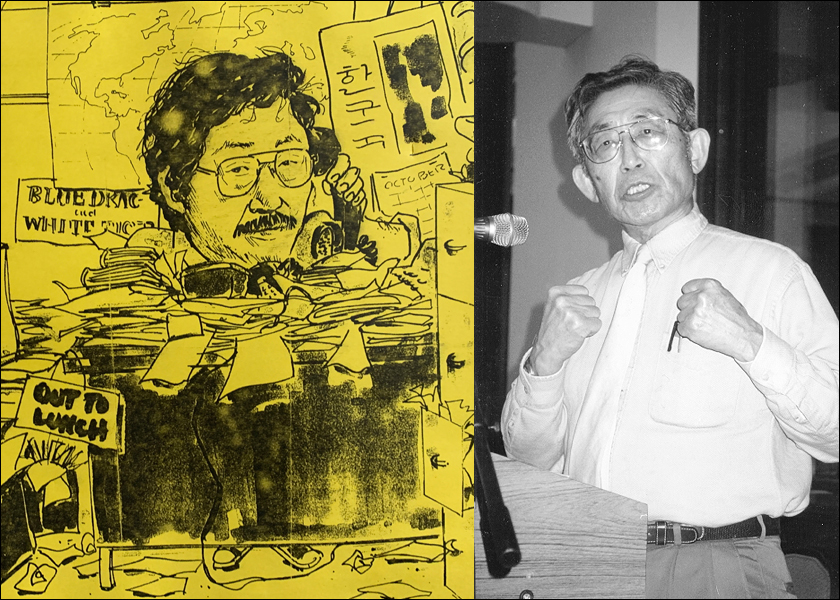

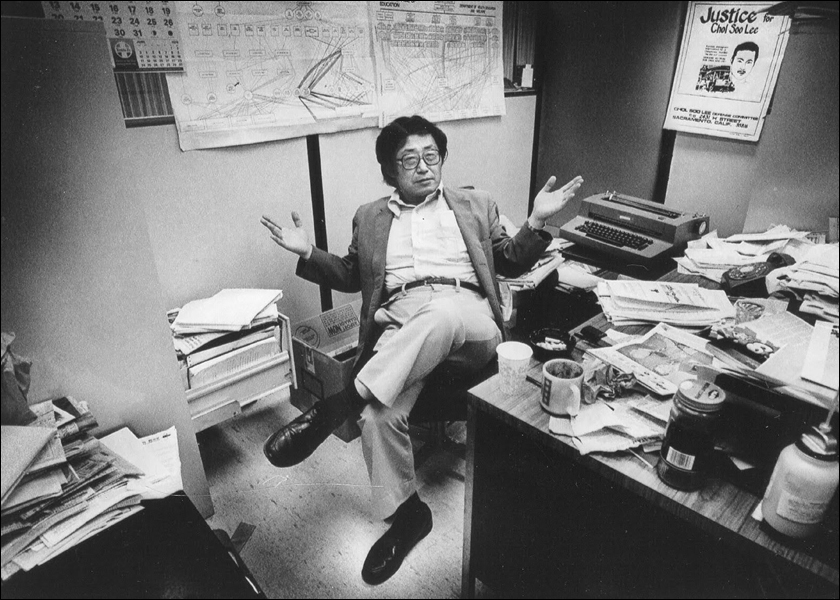

As an investigator, he was called “an obsessive, even maniacal heat-seeking missile” by his editor at the Sacramento Union. As a seasoned editor and journalist, he got the nickname “the godfather of Asian American journalism” after founding two English language newspapers in Los Angeles Koreatown. As an elder mentor, he paid it forward in his later years with outreach to strengthen the community and promote the leadership of the second generation.

Local news reporting has been in trouble nationwide for more than a decade, and most media organizations, whether local or national, cannot even support investigations any more. Ethnic media is scarcer than ever, despite the fact that immigrants are the fastest-growing population group.

For all of those reasons and so many others, the K.W. Lee’s passing on March 8 seems like the end of an era.

Lee, a first-generation immigrant journalist, spent his life with his heart in the Korean American community and his career in the English-speaking media mainstream. Already a mid-career journalist in the ‘70s, he wrote the news of LA Koreatown in the Koreatown Weekly, which debuted in 1979 to a readership of Korean Americans, non-Koreans and English-speaking urban youth and young adults in the Los Angeles area. He became an interpreter of the social predicament of Korean Americans in the ‘80s and ‘90s, when Los Angeles was becoming a boiling pot of racial tensions.

For one of his most compelling causes, he got stunning results – his reporting helped free a man wrongly convicted of murder, and in the process, catalyzed a movement that unleashed the voices of a generation of Korean Americans.

Reporting from the trenches

Within the last few weeks, before K.W. Lee’s death, I was reflecting on him and his colorful life while reading Saigu: Korean and Asian American Journalists Writing Truth to Power, a compilation of reportage from the era of the Los Angeles Riots (or LA Civil Unrest) of 1992 (a day known as Sa-I-Gu, literally “four-two-nine” in Korean). The collection also includes some recent thoughtful essays on the lessons of those times. Lee is a central figure in this colection by 21 contributors, including journalists, scholars, filmmakers, photographers and artists, many of whom are Lee’s former employees and colleagues. I wondered how to write something meaningful about such a comprehensive and wide-ranging collection from a pivotal time.

Its iconic news photos, many by veteran photojournalist Hyungwon Kang, reminded me with a jolt how long ago 30 years actually is. News photos show Koreatown in flames, a broken urban landscape, a war in city streets with armed young men crouched behind cars, ready to protect businesses from looters.

There are also not-so-iconic photos of the reporters of that era, snapshots in time of crowded newsrooms with messy desks and giant dated computers, with tired-looking staff smiling amid the chaos of trying to get the next issue out, feeling perhaps that they were in a moment that should be captured. Those images made me nostalgic for newsroom days.

Meeting him changed people

A commonality in many of the stories was a section on “meeting K.W. Lee” like the one by Sophia Kim, former reporter for the Koreatown Weekly. Many contributors told of how his passion and his example persuaded them to write for their community, even for low and uncertain pay, during hazardous times to be an Asian American reporter in LA.

Kim describes how, out of curiosity, she chased down the editor of the new, scrappy LA newspaper to a small, rented room in the neighborhood. “There I came face-to-face with the man who would become my surrogate father and mentor,” she writes, and describes how, with all the fearlessness of youth, she blurted out that she always wanted to be a reporter. However, she admits in her essay, “Only after meeting with this disheveled middle-aged man with glasses and a foul mouth, did I ever think that going into print journalism was at all a possibility.” He hired her on the spot.

It made me think of how I first met Lee. It was many years later. Lee was retired, still writing from time to time, but more engaged in leadership to his beloved community. Two years before we met, in 1997, I had co-founded Korean Quarterly with a group from our Korean American church and our Korean school. It was an uncertain time. I still did not know after two years if I was embarking on a short-term or long-term project.

I drove up to Sacramento from LA to meet him at his home. I remember it was the first time I had ever used Google maps, and also my first solo road trip in California. I printed out pages, and had my maps laid out in a notebook, turning the pages in my rental car as I drove north through the almond groves to the scenic capitol city.

I had flown to Los Angeles to do a story about LA Koreatown. I wanted to talk to some of the people who lived through Sa-I-Gu, and tell the story of the area’s recovery from the civil unrest a few years on. Koreatown was still full of empty, blackened lots and still inhabited by the people who had survived that war. My brain was full of those images and the reflections of its people as I headed to sunny Sacramento.

I was curious because so many people had urged me to go and meet K.W. Lee. I knew he would be a good interview, as a person who had been writing for years about Koreatown and Korean American topics. Turns out, he was equally interested in talking to me. That first meeting lasted a few hours, chatting about the characteristics of the Korean American community we covered. I was cheered by the visit, and lighter, feeling that I finally had an elder mentor to look to.

After that, we emailed for a couple years, and eventually he visited the Twin Cities to be the keynote speaker at Korean Quarterly’s fifth anniversary celebration, where he got to meet with some of the many adult Korean adoptee contributors and second-generation contributors to our newspaper. He wrote several pieces for us, including an essay, Today’s Korean America is in the heart, in the Fall 2002 issue, in which he described the divisive Korean American community he had observed as a reporter and tried to improve upon through community outreach activities as a retiree. He also wrote of finding Korean American community spirit in unexpected places, even the Twin Cities. He described the existence of Korean Quarterly as “a small miracle.”

Lee had always kept me on his email list. He sent his own musings and pieces of news from time to time to a large group to colleagues and people he mentored, and I was very honored to be a recipient. Reflecting on how to write about the Saigu book, and how he was a central figure in the journalism that was so key to that time, I wondered whether a short interview with him might still be possible, although I knew he must be in his 90s. The stories in Saigu are cleverly pieced together, but it is a long and winding story to learn about how Koreatown found its voice. I was thinking that it would be a perfect focus for the article to be able to quote this famous anti-hero whose courage inspired an entire generation.

It was right then that I learned that he was gone. He died peacefully and with his family around him on March 8, at age 96. I felt I had missed a last chance to connect with a mentor who I had always admired and enjoyed; someone who always inspired me to promote community and be true to the best principles of journalism.

The feeling was bittersweet. I was so sorry to hear of his death, but felt joy for his well-lived life, for the gift of his great mind, tireless capacity for work, big personality, belief in the power of the press, and quest for justice that inspired a community at a crucial time and place. I felt grateful for his care and encouragement for the next generation, and how so many people he mentored went on to lead in their own ways at his urging and because of his example.

I am especially grateful that he reached out to the very inexperienced staff and supporters behind a small Korean American quarterly newspaper way over in the northern Midwest.

The man on the moon

Reading about the arc of K.W. Lee’s life, it can’t be overstated how unlikely it was that a Korean immigrant, even a well-educated early immigrant with a sophisticated command of English, could become the country’s most respected Asian American journalist.

In a Saigu essay by Soojin Kim, she writes that he described himself as “a man on the moon” after he immigrated in 1950 to study English at West Virginia University, with the intent of returning to South Korea after graduation. There were only a handful of Korean students in the U.S. that long ago. He immigrated before the Korean War, and was unable to return after the war began in 1951. After earning a graduate degree, he got two successive reporting jobs in the south, where the gulf between whites and Blacks was wide, and civil rights causes had barely begun.

Lee, however, was writing about early civil rights issues in the south years before the Civil Rights era truly began, starting with his work at the Kingsport Times-News in Tennessee, as the first Asian immigrant to report for a mainstream daily newspaper. While working for the Charlotte Gazette in West Virginia in the ’50s and ’60s, Lee covered the Civil Rights movement in the south and plight of Appalachian coal miners.

On death row due to a mistaken identity

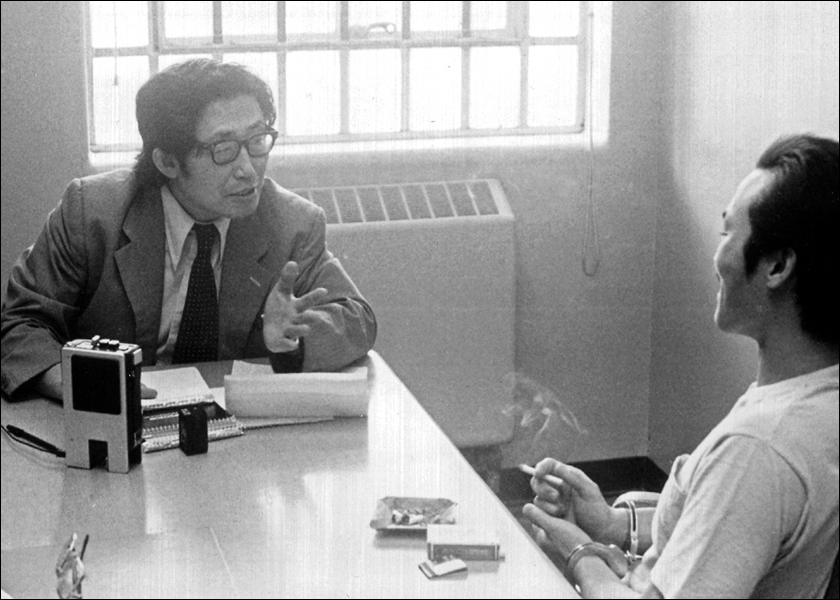

Among many stories Lee pursued over his career, probably his most famous was his campaign to reverse the murder conviction of Chol Soo Lee. K.W. Lee met Chol Soo Lee in 1974 in prison – Chol Soo Lee had been convicted of murder, but had maintained that the conviction was false, that he was mistakenly identified as the shooter of the Chinatown gang leader who was killed. K.W. Lee, who was working for the Sacramento Union at that time, saw many errors of omission and negligence in the case. The two visited and developed an active correspondence by letter.

Chol Soo Lee was convicted for murder a second time while in prison; he killed a fellow prisoner in self-defense, a member of an Aryan Brotherhood gang. K.W. Lee’s dogged coverage of the fight for Chol Soo Lee’s freedom went on for years, and continued after his founding of the Koreatown Weekly.

During that time, the Korean American first generation consisted mainly of small business entrepreneurs, many of whom lived within the bubble of Koreatown with little English proficiency or cultural competence about their new country. The Free Chol Soo Lee campaign united Korean Americans around a righteous cause.

That newspaper continued until 1984. Chol Soo Lee spent five years on death row before receiving a new trial, and then was acquitted in 1983, chiefly due to K.W’s investigative work, which comprised 120 articles written over a period of five years.

Chol Soo Lee’s redemption was later described in a 1989 feature film True Believer, starring James Woods and Robert Downing, Jr.; it was loosely based on K.W. Lee’s involvement. Lee’s work on the case, and the consequent social justice movement, was more recently portrayed in the 2022 Emmy-winning documentary film Free Chol Soo Lee.

Unity in the community

K.W, Lee also established and edited the English edition of the Korea Times in 1990 in Los Angeles, to provide fairer coverage and promote unity for a Korean American community mired in racial tensions. Lee always used his communications pipeline across the language divide as a kind of bully pulpit, to beg and exhort second generation immigrants – an educated, and culturally and linguistically-capable group of young adults – to speak for their parents’ generation.

His agitation for community leadership became more strident after the events of 1992. There was a jury verdict of “not guilty” on April 29 that year for four white officers in the 1991 beating of African American Rodney King after a traffic stop. A bystander videotaped the horrendous beating, which ran repeatedly on cable TV’s CNN News.

The April 29 verdict was the spark that set off race-based Black-on-Korean looting, arson and violence in Koreatown known to Koreans as Sa-I-Gu, a rampage that caused one person’s death, thousands of injuries and $1 billion in property damage over the six days that followed.

K.W. Lee was hospitalized during those six days of rioting after collapsing in pain, being rushed to the hospital in a colleague’s car, and then to the UCLA transplant center where he had a life-saving liver transplant. He would often talk of how he appreciated the irony of the racial unrest and violence going on all around him, while he was holed up quietly waiting for his transplant, silently thanking his donor – a stranger who might have been Asian, Black or white – for the miracle of a second chance.

In one essay on the LA uprising, he describes laying there, and hearing a voice whisper “put off dying for the duration.” He wrote that he then “sat up in my sickbed, and, with shaky hands, began editing reams of copy from the nine undaunted staffers – mostly fresh from college or still in college or high school – bravely holding out in the battle zone” of the Korea Times English Edition.

Along with other Korean American leaders of the time, K.W. Lee attributed the extent of race-based violence in part on the immigrant generation’s lack of cultural and language competency and lack of sophisticated leadership that resulted from that. The solution, he believed, was to urge the second generation to step up and assume a leadership role. To do that, the younger generation had to be persuaded and motivated to return to Koreatown or other Korean American urban communities, and assume leadership roles, not to flee their home cities to become doctors, lawyers, and business professionals in the mainstream.

One of many young adults who paid it forward in building up community in the wake of the riots was Do Kim, who returned to Koreatown, after becoming a Harvard-educated lawyer, to work for civil rights activism in his old neighborhood. Meeting K.W. Lee inspired him to return and then stay there to help the next generation of Korean Americans. With Lee, Kim founded the K.W. Center for Leadership, still an active organization, which runs a program to inspire leadership in Koreatown youth.

Twenty years after Sa-I-Gu, Lee gave one of his more famous speeches, entitled The Fire Next Time in Koreatown at the 20th anniversary of that event, in which he warned that the generation coming after the Sa-I-Gu generation – 20 years since the fires blazed – still has a responsibility to stand up for their immigrant parents’ generation, and that the job of producing leaders for the next generation is ongoing:

Come the next fire, your English-speaking generation is destined to become the first and last line of defense for your half-deaf and half-blind parent generation of silence and sacrifice, as your older brothers and sisters demonstrated in the last fire of Sa-I-Gu.

Many accolades

Lee spent over 40 years working as a reporter, editor, and publisher for various mainstream and ethnic publications, winning 29 professional awards in his career. In 1987, Lee co-founded the Korean American Journalists Association to provide recognition and professional development for Korean American journalists nationwide. In 1990, Lee also established and edited the English edition of the Korea Times in Los Angeles, to provide fairer coverage for a Korean American community mired in racial tensions.

Following the LA Riots of 1992, Lee was one of two recipients to be honored by Los Angeles County for his efforts in “promoting racial harmony in inter-group relations through journalism and community involvement.”

In 1987, Lee was the first recipient of the Asian American Journalists’ Association’s (AAJA) Lifetime Achievement Award. He earned numerous other accolades, including the National Headliners Award from the National Headliners Club (1974 and 1983) and the Freedom Forum’s Free Spirit Award (1994), according to an AAJA remembrance. After his retirement from the Sacramento Union in 1994, he lectured and taught investigative journalism, and contributed to Korean American and other Asian American publications (Korea Times English Edition, KoreAm Journal, and Nichi Bei Weekly, in addition to Korean Quarterly).

In 2010, he was honored at AAJA’s national convention as an Asian American Founder and Pioneer in U.S. Journalism for his lasting contributions. AAJA’s forthcoming book, Intersections: A Journalistic History of Asian Pacific America, chronicles the legacy of Chol Soo Lee’s story in a chapter by Julie Ha, the co-director of Free Chol Soo Lee.

I wonder this week what K.W. Lee would make of recent assaults on press freedoms and violations of the civil rights of immigrants, particularly those who have been detained or deported without due process. I know he would be grieved and appalled, but also loaded for bear, in front of his keyboard, and ready for action with all the facts in hand.

To know that we are not alone

The kind of energy K.W. Lee embodied to sort out truth from fiction and report it, defend civil rights and equality, promote leadership of immigrant communities and encourage the next generation are all needed as much today as they were needed in the 1970s, ‘80s, and ‘90s.

As a war-hardened veteran of an embattled time, K.W. Lee warned us to be prepared for the “fire next time” if race-based tensions in our local and larger communities continued. He was sure, however, that the repeating pattern of division can be remedied by raising up leadership, building a supportive community, and having a sense of history so as not to repeat the past.

Reporting and writing can be difficult and solitary. Sometimes we wonder if anyone is paying attention. But K.W. Lee had a different view. In her essay on the accomplishments of K.W. Lee, Saigu contributor Sojin Kim quotes him as saying “It’s why we write and why we read: To know that we are not alone.”

We are both richer and wiser for appreciating the work of this “godfather of Asian American journalism,” and following his courageous example. And to honor his memory, we should keep building community, and know we are not alone.

Editor’s note: There will be Celebration of Life for K.W. Lee on May 24, 2 to 4 p.m. for all friends and community members at the Oxford Palace Hotel, 745 S. Oxford Ave., Los Angeles 90005. For more information contact Do Kim at the K.W. Lee Center for Leadership (email: dokim@kwleecenter.org).

Photos are printed with permission of the UCLA Press.