Textile artist highlights treasured Korean petroglyphs in local exhibition | By Stephen Wunrow (Fall 2019 issue)

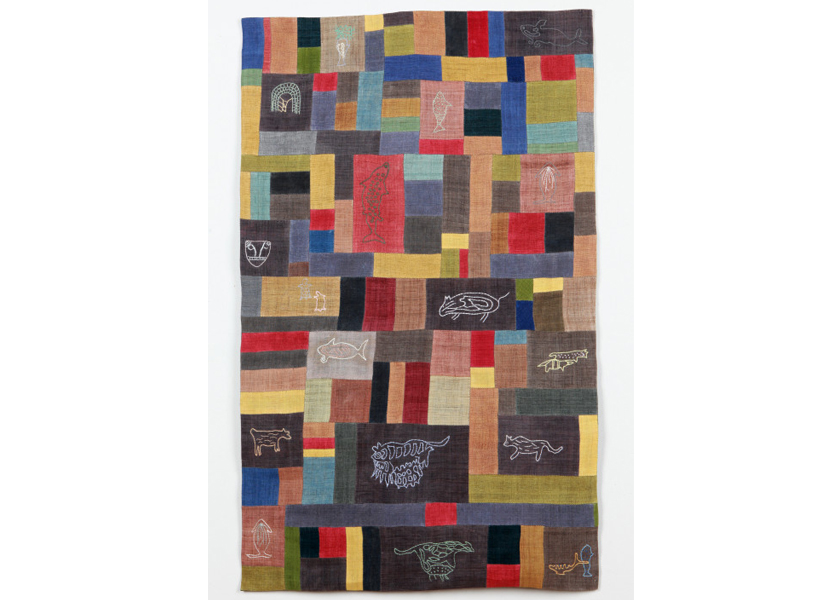

The Minnesota Textile Center hosted an exhibition of a well-known artist, Insook Choi, whose wrapping cloth creations, known as bojagi, have won many honors in Korea. The designs of the bojagi that were exhibited in Minneapolis mirror the forms of ancient rock illustrations, or petroglyphs, that are on the cliff walls near her hometown of Ulsan.

Fellow bojagi artist Chunghie Lee, who arranged for the Minnesota exhibit and translated for the artist during an interview, said she introduced the Textile Center to Choi’s work, and informed them that Choi’s work is particularly interesting due to its social consciousness and advocacy for the care and preservation of the petroglyphs, which is one of Ulsan’s most treasured cultural resources.

Lee networks with bojagi artists globally to further the international appeal of this art form, and organizes a semi-annual gathering The Bojagi Forum, in Korea.

The exhibit Ulsan Bangudae shows Choi’s hand-stitched and embroidered hemp and silk work reflecting the imagery of the prehistoric Bangudae Petroglyphs.

Bojagi are assembled similar to the top of a quilt, using pieces of various matching or contrasting fabrics in a pattern. In tradition, Koreans wrapped many things in bojagi for either storage or for carrying, such as groceries, lunchboxes, pots and gifts. Wrapping cloths were made of useless scraps, but women’s imaginations made them into functional crafts, and even works of art.

Today, bojagi are made as a craft and art form, and the genre has spread to many countries. The art form varies greatly across artists and cultures. Traditional Korean bojagi has a geometric pattern, but more modern interpretations of the form use organic pieces and shapes. It can be plain or embroidered, dyed a solid color or with some dye pattern, such as tie-dye. Some bojagi are made from a thick woven fabric, others are so thin that they are translucent.

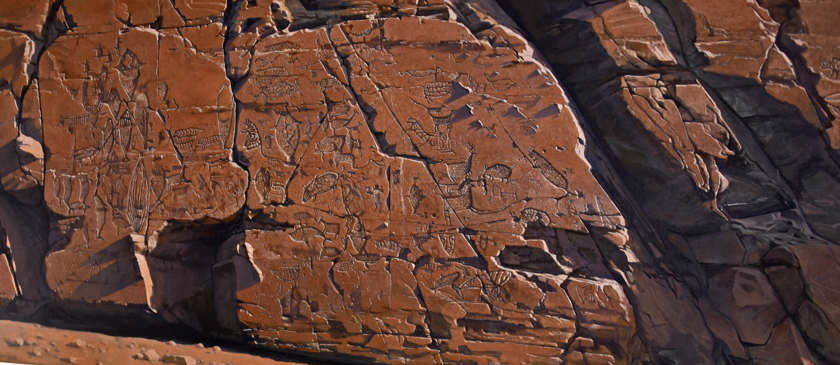

The word “Bangudae” refers to the place-name of one of two petroglyph sites in the area. It is a vertical rock face on a river in Ulsan; the area of rock inscriptions is roughly 33 feet tall and 33 feet wide. They depict animals, people, hunting and fishing tools and textual symbols. The petroglyphs were carved into the rock between 3,500 to 7,000 years ago.

Interestingly, the Bangudae Petroglyphs depict many whales of different types, as seen in the water from above, as well as images of people whale-hunting. It is the oldest illustration of whale hunting ever found, according to information from the Ulsan Petroglyph Museum.

Choi includes some reproductions of the whale petroglyphs in her work, embroidering these and other animal images with the complex inner lines and swirls that are seen in the petroglyphs. In one of the bojagi in the current exhibit, she tie-dyes some of the individual pieces to resemble a fault or crack in a rock.

The artist has been designated a Master of Bojagi by the Federation of Artistic and Cultural Organizations in Korea. She uses the images of the petroglyphs to raise awareness of the need to preserve these and other important cultural artifacts, and to show pride and affection for her heritage, Lee said.

Choi said she made her first bojagi about 50 years ago, after a friend asked her to help with a bojagi project. She entered her first bojagi, a wrapping cloth for a lunchbox, in a contest, and to her surprise, it won an award. Since then, she said, she has delved more deeply into the art form, at first as an amateur, and in 2009, by studying the art form at an art university in Korea.

She was always interested in color composition and the amazing combinations of shapes and patterns possible with bojagi work. She eventually became interested in natural dye. She composes her own colors for fabrics, using natural dyes on silk and ramie fabrics. These include the indigo plant, persimmon tannin, chestnut shell, gallnut, sappan wood, balsam wood and acorn shell, according to the labels in her exhibit. She was awarded a gold prize in the International Dye Contest, held in Daegu, South Korea.

Choi has exhibited more than 200 times nationally and internationally. Her exhibition at the Minnesota Textile Center was October 2019.

Korean Quarterly is dedicated to producing quality non-profit independent journalism rooted in the Korean American community. Please support us by subscribing, donating, or making a purchase through our store.