Snows of Kilimanjaro by Yearn Hong Choi

(independently published, 2020, ISBN #979-8-6784-5960-7)

Review by Woo Ae Yi (Fall 2020 issue)

Yearn Hong Choi introduces Snows of Kilimanjaro as possibly his last poetry book, and I understand that because he has currently been undergoing pancreatic cancer treatment, as he mentions in his poem A Poet, Golf and Pancreas Cancer. He even mentions death in his poem South Col, implying that he would rather be cryogenically frozen than to undergo tortuous cancer treatment. If he doesn’t die from cancer, he warns his reader that one could die from an accident, in the poem An Accident Report, and ironically prized his crutches in Memorabilia.

In the middle of summer, I write a book review of Snows of Kilimanjaro, a nice reprieve from the blistering heat, in the hope of getting this review out by the fall or wintertime. The theme of the first part of this book is obvious; snowy mountains or snow and mountains, so it’s appropriate that I write this review from Denver, Colorado, known for both. Even Calgary Stampede speaks of love for the Wild West and the poem Aurora Borealis, though about the Northern Lights in Norway, has a name like Aurora, Colorado.

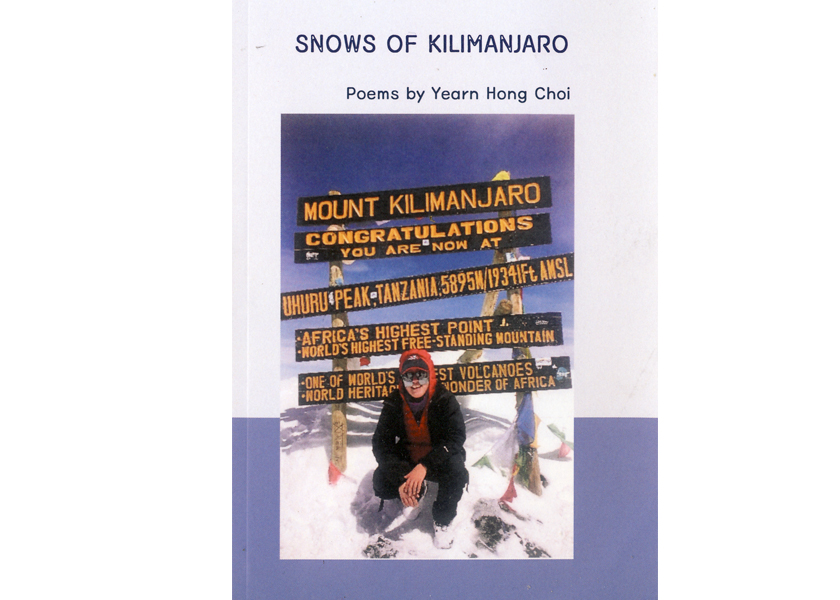

The first poem of the book is Snows of Kilimanjaro, inspired by Ernest Hemingway. Hemingway also shows up later in Baseball. A poem about Mount Kilimanjaro is an appropriate way to start the book, as people know that climbing Mount Kilimanjaro is quite the feat and, as a possible last book, it’s appropriate to highlight lifetime accomplishments and show that he has reached the “pinnacle” of his success.

I appreciate the end of this poem. Instead of saying veni, vidi, vici, Latin for “I came, I saw, I conquered,” he exchanges vici for amavi, a combination of amor (love) and vita (life). It reminds me of a quote by Brandon Burchard, a motivational speaker and self-help guru, who has made popular the phrase “Did I live? Did I love? Did I matter?” Along the same lines, Choi’s poem Typo reminds me of the quote, “Those who live passionately/Teach us how to love/Those who love passionately/Teach us how to live” by Parahansa Yogananda.

Some have said that Eskimos have at least 50 words for snow and similarly Dr. Choi’s treatment of snow is varied. Snow represents everything from frozen fish in South Col to life, in Ode to Aomori Under the First Snow to a snow angel metaphor in Kiss the Snow to the Ice Age in Post Card from Winter Rocky Mountains to a snowstorm in Ode to Snowstorm and snow blowing in Neighbors.

Mountains are as prevalent as snow. Part of this could be because his friend told him “Dr. Choi, you made a mountain, and I just planted a tree on it.” His friend died before the book was published.

Not all of the first part of the book is “cold.” In his search for heights and amazing experiences, he also came across the Arenal Volcano of Costa Rica, one of the most active volcanoes of the world, in Costa Rica and Ode to Morning Coffee and makes volcano metaphors in Tango. Heights can also translate to space, as he visits the Johnson Space Center in Houston.

He has shared many more of his seasonal travel experiences within this book, including parts of the world connected to Buddhism and China as we see in The Silk Road, Splendor in the Mongolian Wilderness and Genghis Khan (refered to as Temujin), and Bangudae Petroglyph. He experiences heartwarming human moments with others and is awestruck by the beauty of life, using words and poetry to best describe his experiences, fluctuating from one-word per line poems as in Dance to full-on prose in Elegy 2.

The themes for the second part of the book are local sports plus current daily politics in both the U.S. and Korea. As the average person experiences politics mostly by reading the news, there’s less emphasis on active adventuring as in the first part of the book and more emphasis on being an awestruck onlooker in the audience. This passivity mixed with wonder is particularly evident in poems about watching sports or the Olympics in Baseball, At last, the Nationals are Champs, Synchronized Swimmers, and Ode to the Capitals!

Discussing social politics is almost “par for the course” for any poet living in the U.S. in 2020. He refers to the U.S. as a “war torn country” in Labyrinth and can’t help but criticize Trump and Trumpers, as hardly anyone can avoid talking about him or them nowadays.

Even though his poems are left-leaning by American political standards, they are right-leaning by Korean standards, as he questions the good it would do to reunify with North Korea, a country that is so far removed from South Korea as we see in Panmunjom Poem and #MeToo. In #MeToo he criticizes a famous monk who had sexually harassed a famous poet and briefly mentions Stockholm, both an actual city and an indirect reference to “Stockholm Syndrome.” His political activism makes sense because he started his American life in anti-war activism and submitted poems to The Indiana Daily, which also supported civil rights activists in the 1960s. In the 1970s, he was so against the authoritarian South Korean government that he could not return to South Korea.

The theme for the third part of the book is an ode to his Korean family, and composed of multiple poems. He misses Korea and ponders if Canadian geese miss their hometown too in Canadian Geese. His poem Genealogy discusses the Korean emphasis on the importance of the first-born son, saying that he is the first-born son of a first-born son and that his first-born son has had his first-born son.

His experience must be rare in Korea for his father wanted him to be a poet, but in Name, it is evident that Korean society thinks very differently. He shares the love he has with his wife in Honeymoon Haiku (both in Jeju and Hawaii), the love for his ancestors in Eggs in the Internet Nest, and the love for his progeny in To You, My Love in which he shares that love has been an enduring theme throughout all generations in his family.

He has a smaller section entitled Four Poems from Pusan, Korea which features poems about the Korean War. Some of the poems in this section are not about his immediate family, but perhaps about the larger family of Korean poets or Korean artists in general, like in The Yoon Dong-ju de Compostella, At the Rikkyo Campus, Miss Ji Hae Park, The Violinist, or Mr. Chung Ho-seung, Korean Poet, a poem he uses to tie back to the first part of the book about snowy mountains.

Death is prevalent near the latter part of his book, a testament to his own mortality. Not only does he speak well of his family and friends, but he also talks about how much his mother sacrificed for him so he could go to the U.S. and how much he sacrificed for her (such as giving up his naturalized U.S. citizenship in order to return to Korea to take care of her), lamenting that all he did was not enough. He has a series of elegy poems and another poem about attending multiple funeral services in One Spring Day in 2017. His regrets in The Evanescence hit a personal chord in me as he talks about reaching out to people he cared for, only to find out that they had already died.

This entire book could be used as his own elegy or eulogy to himself as he says, “Well, we came like a Spring flower and go away / in thousand winds that blow. / In between, I enjoy poetry and music and appreciate arts. / I am grateful to my life given”

This is much more than just a book about nature or the environment or politics and family; it is a book about accomplishments, achievements, and adventure. Choi’s love and celebration of life is clearly obvious in his preparation to say goodbye in the future, but one hopes, as is inferred in A Poet, Golf and Pancreatic Cancer that his hopefulness will give him more time to live with love and to continue to reflect on his love of life.