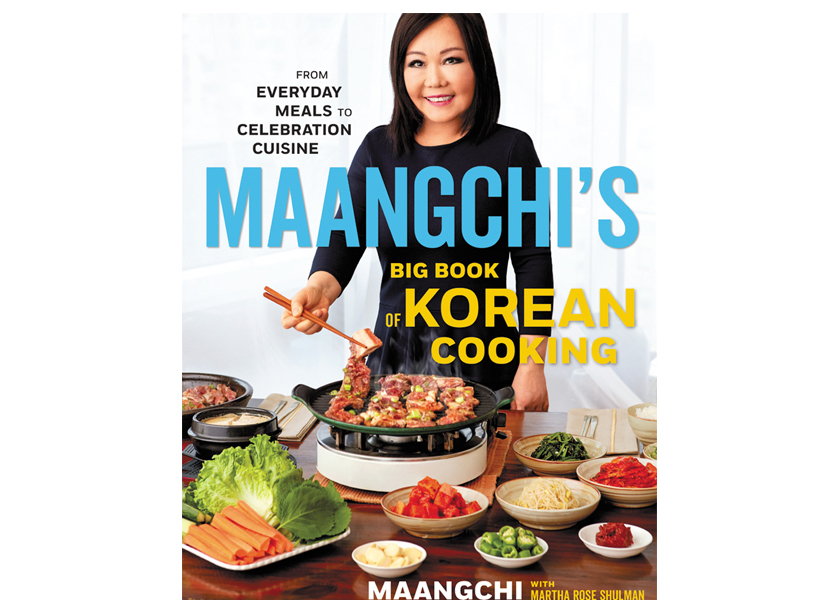

Cheery internet chef’s new cookbook is a serious look at Korean traditional and modern cuisine | Author Interview by Martha Vickery (Fall 2019 issue)

Bright and full of personality on camera, internet chef Maangchi thought she was starting a new hobby when she started doing on-line cooking lessons back in 2007.

But with the publication of her latest book Maangchi’s Big Book of Korean Cooking (published October 2019), this self-taught chef has moved into a new phase of her career. Her detailed writing and photography, even the photos of all her meticulous, handwritten notes captured in the book, show her expertise, passion and depth of knowledge of Korean cuisine and how it has informed her colorful life.

Her longstanding reputation for delivering reliable, easy-to-learn Korean recipes in a fun format has already earned her a loyal audience. From the stories in her cookbooks, that loyal audience can learn more about the background of the real Maangchi, the first-generation immigrant Emily Kim, her own history, and the loving, traditional family she left in South Korea.

A recent New York Times interview referred to her as “Youtube’s Korean Julia Child.” There are some similarities between the two self-made media chefs. Julia Child opened up the mysteries of French cuisine to an American audience in the ‘60s, at a time when Americans were making a lot of entrees with cans of cream of mushroom soup. Maangchi rode the wave of hallyu (Korean pop culture), opening up Korean cuisine during a time when Americans knew little about Korean cuisine, but were hungry for it because of the emerging popularity of Korean music and films. A recent estimate put her subscriber base at 3.7 million. The New York Times recently named her new cookbook as one of the 13 best cookbooks of 2019.

Like Julia Child, Maangchi started her career in a humble and low-key manner, building it up as time went by. Her happy-go-lucky manner on the screen belies her seriousness about teaching effectively, and building a recipe methodically; from choosing the right ingredients to paying attention to the presentation of the dish at the end. Often, she does all this while wearing a funny hat or a ridiculously large bow in her hair.

Kim’s use of language is also interesting —- she has a strong accent, but a very technical and precise vocabulary, which helps Korean cooking students learn. She talks cuts of meat like a butcher, and wields a knife like a ninja warrior.

She also takes full advantage of the strengths of the video format and how it can enhance the learning experience. She zooms in for helpful closeups —- how cabbage leaves should look when they have been salted enough, or how to hold a slice of radish up to the light to check its thinness by the translucence.

Just from one phone interview, it’s apparent that her cheer and love of life is also genuine. Sometimes she will caution the viewers about the “tricky” part of a recipe and then exclaim about “the fun part.” Tasting her dishes at the end, she never simply says “yum.” Instead, she puts into words exactly how the thing should taste, the textures and colors to experience, and how it should look.

Many food preparation methods in Korea are unknown in the west. There is the salting down and preservation of vegetables in kimchi, of course. There are also other types of fermenting, drying, reconstituting, and broth-making that westerners need to learn to successfully execute Korean dishes. Even with the most complex recipes, Maangchi can make it seem doable.

Maangchi (Emily Kim), prior to 2007, was living in Toronto. She was divorced with two adult sons; one was studying computer science and IT. Kim was very into online gaming back then, and “Maangchi” was her tough-gal online avatar —- it means “The Hammer.” She was admittedly a gaming addict, communing with gaming friends online and playing until late at night. She also had a blog, so she had had some experience with the social media of the day, and was familiar with the concept of online friends.

At one point, her son suggested to her that doing online cooking videos might be a better use of her time. “It was around that time that Youtube was just beginning,” she said. “At first I thought ‘no, that’s impossible because I don’t want to show my face,’” she said. “But he was encouraging and told me it would not be so hard.”

Trying to persuade her, he suggested “how about showing only your hands instead of showing your face?” She thought about it some more. Kim describes herself as a person who likes to stay busy, so the idea of a new project was attractive. She had had various outside interests that suited her outgoing personality; one was in helping and counseling other Korean immigrant women, particularly those who had experienced domestic abuse. She worked with women to help them settle and get connected with social services. She also did translation and interpretation. She ran a monthly self-help group, and she would always make the dinner.

She viewed the YouTube video idea as another opportunity to share with others. “I was always interested in sharing my recipes, and I thought if I decided to do this, I should show my whole self, not just my hands. Starting is really important, you know? I wanted to start right.”

Using a rather “blurry, cheap camera,” she and her son made their first cooking video, for spicy fried squid (ojingae bokkum). “I didn’t know who would watch my video,” she recalled. “I thought maybe no one would watch it, but anyway, we made it and posted it.”

But “right after we posted the video, people started to subscribe suddenly. How they found it, I don’t know. I was so surprised!” The comments were “all encouraging words,” she said. “They were saying ‘oh, it’s so good,’ and ‘oh, can you tell me how to make Korean doenjang chigae?’ Or Korean chapchae, or kimchi, others were asking.”

She was onto something, she knew that day. “I was so happy. And [having the Youtube channel] allowed me to interact with all those guys. They became my friends.” They wrote to her on the Youtube channel, and she enthusiastically wrote back. Not wanting to disappoint her new-found friends, she kept making videos of requested recipes. The next video was soybean paste soup (doenjang chigae), another very Korean classic.

On the 10th anniversary of her first cooking video in 2017, Kim re-made the first video of instructions for spicy fried squid. There were only “some small clips of the original,” she said. She received comments back after posting that one which made her proud. “Some told me they have grown up watching me,” from childhood to adulthood during those 10 years, she said.

“In another 10 years, can I make this kind of nice videos?” she asks the audience in her 10th anniversary video for ojingae-bokkum. “I’m not sure, but I am living every single moment, happy with my passion for cooking and sharing my recipes. I’ll keep making videos until I cannot make them,” she pledged.

The contrast between the 2007 spicy squid video and the 2017 remake is interesting. The 2007 looks like a home movie —- jiggly and blurry in some spots, with inconsistent audio. An oven timer goes off in the middle of filming and she comically rushes off camera to turn it off. In the 2017 video, she is relaxed, smiley, a bit philosophical about how fast the 10 years have gone by. She even shows a picture of her original Maangchi avatar she used for her gaming character. She pops a bottle of champagne at the end that explodes all over the squid and banchan, but it is a fitting finish to the celebratory video. She just laughs. “Let’s keep encouraging each other!” she says.

The videos and recipes proliferated over the years. The background changed, from her Toronto apartment to an even tinier New York apartment near Times Square, and more recently, to a spacious kitchen with a professional-looking stainless steel double fridge in the background. These days, her videos attract enough online advertising that she can afford to do it full time.

She ventured into the cookbook business as a way to organize and categorize some of her many recipes. Her first print cookbook was Cooking Real Korean Food with Maangchi. Before that, she had three downloadable e-books on the website, she said, but the self-published print books were too expensive for readers to buy, “I love color, and I wanted to make a colorful book with a lot of photos. To do that, I had to give up making any profit” on the printed versions, she explained.

Because she had spent years interacting with her readers, Kim already had a clear idea of who her viewers were and what they wanted. That knowledge informed her first print book (Cooking Real Korean Food with Maangchi), as well as the recent one, Maangchi’s Big Book of Korean Cooking.

There were other good reasons to go with a mainstream publisher. “They were interested in working with me,” she said. “They gave me a good writer to work with. Because English is not my first language, she helped me a lot.”

For her recent book, Kim did a lot of original culinary research. She collected some Korean fusion recipes from chefs in the U.S. and went to a women’s Buddhist monastery in Korea to learn about traditional Buddhist cooking.

She also wrote a section on recipes for Korean lunchboxes, or dosirak. She is an expert on that topic, from being a mom in Korea. She describes the preparation of dosirak as competitive among the students’ moms. It was also an essential task, since students spend many hours at school and often need a lunch box and a dinner box.

Another area of her expertise is seafood. Growing up in Yeosu, on the south coast of South Korea, Kim’s father ran a seafood auction. “Our house was always full of fresh seafood,” she said.

Temple cuisine is a popular trend in Korea, and Kim did some R and D to get her temple cuisine recipes, visiting a women’s temple high in the mountains of South Gyeongsang Province, where the cook helped her learn the specific tastes of temple food, which is vegetarian and omits garlic, onions and hot peppers.

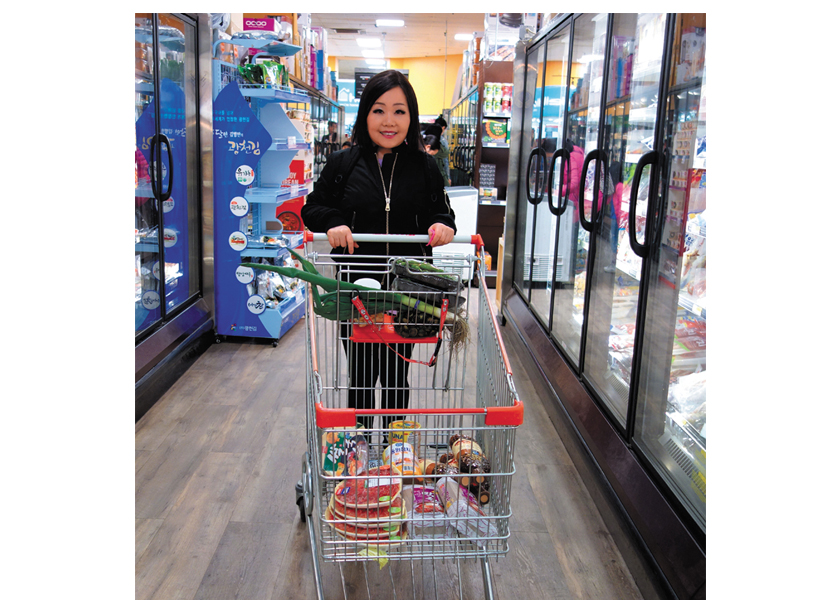

The new book also contains basics, such as names of Korean grocery products, and a photo of what the product will look like in the store; it is her effort to de-mystify the experience of shopping for Korean groceries. There is also a section on Korean kitchenware.

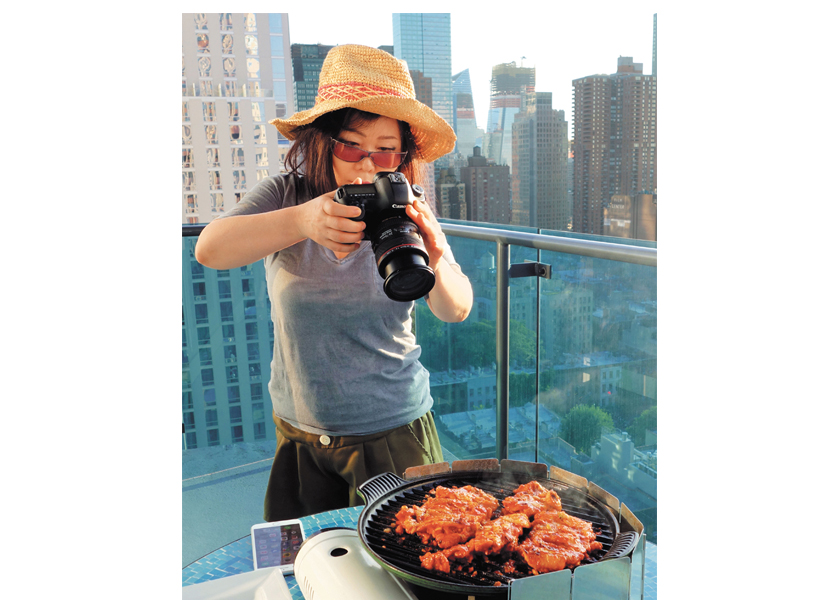

A skilled amateur photographer, Kim also took thousands of photos for her cookbooks, as she has been doing for the website for many years. The final product has 150 recipes and is 400 pages long. Now, at the end of what was an enormously complex project, Kim considers the finished product to be a life achievement.

Every family has a star cook, and in Kim’s family, it was her grandmother. The head of their big extended family household, Kim relates one story in the new book about her grandmother unlocking the grain storage building at their home every morning, and giving her aunt the rice, barley and other dry goods for the day, then locking it back up again. It is a memory about frugality they lived with, and the specialness of food. Most of her traditional recipes are ways of cooking she learned from her aunt, mom or grandmother, “but many of the modern-style recipes are from a friend who studied cooking at university,” she said.

One of the most difficult skills of becoming an internet chef was learning to create her own recipes. People in Korea seldom learn cooking through recipes; instead, they watch and learn from an accomplished cook. Amounts of ingredients are approximate and to individual taste. “It was a really big challenge,” when she first began to develop recipes for her videos and website, “because I had never measured in my whole life. But, I had to do it.”

She remembers calculating and recording ingredients painstakingly. For example, she would grab the right amount of garlic, then look at what was in her hand, and count out the cloves. “Then I would grab the right amount of salt, look at it, then approximate in the recipe how much salt I use. It was very challenging, and at the beginning, I made some mistakes … Now, I can easily figure out what measurements look like.”

Kim said she understands how people learning alone in their kitchen with their computers need a recipe. In recent videos, she has begun to post Korean captions on the videos as she chatters away in English. The captions, she said, are for her Korean-speaking viewers. Korean cooks these days need recipes too. “They are viewing and learning from websites and books. Not like me!”

The final product should be a real Korean dish, and “if viewers follow it step by step, then can make the same dish as I make, and the taste should be an authentic taste. Even a beginner can make like a Korean black bean sauce, and Korean friends will say it is delicious. I hear this kind of story a lot.” Kim also adds a lot of detail in her recipes on how to customize the dishes to be vegan, or less spicy, showing that she understands how users have a variety of food preferences and dietary needs.

Kim said she is scanning for new recipes as she goes to restaurants, or watches Korean programs. “That is my life —- all the time, I think about Korean food!” She admits to a funny habit —- when she sits down to eat something new, she wants to concentrate on it —- the taste, temperature, level of spice, the way it looks. “When I eat something with my mom and sisters, I don’t want to be interrupted by anyone, and I just tell them I want to be quiet,” she said.

Kim wrote in her cookbook about how she was reluctant about producing another cookbook. “I knew I would be working for a couple years,” she said. She decided, finally that she had to do it before she got too old to take on such a challenging project, and she went for it.

It did take a couple years of solid work, during which she would develop a recipe, and send it to her editor, New York Times food columnist Martha Rose Shulman, who would follow it and test everything in the recipe. Shulman would adjust the descriptions as needed. The two worked well together, but the pace was fast, and the process was labor intensive.

Her intent with her cookbook was to refine and improve old recipes. “I never just copied and pasted from the website!” she said. She invented a simpler way to make chapchae, a noodle dish that often is made with multiple steps. She developed versions of dishes with either seafood, meat or vegetarian. “My husband said that while I was dreaming one night, I said ‘one cup of hot pepper flakes’ in my sleep!” she said.

Kim is happy with the result, and even happier that the project is complete. The result is a comprehensive book with bright visuals and recipes for many dietary needs and palates. Overall, it is a work that shows the depth of Korean cuisine, and the care of one chef instructor who invested many years in becoming friends with her students. Maangchi’s Big Book of Korean Food contains the same enthusiasm and encouragement of beginners that makes her videos irresistible.

Korean Quarterly is dedicated to producing quality non-profit independent journalism rooted in the Korean American community. Please support us by subscribing, donating, or making a purchase through our store.