Writers pen accounts of the painful and joyful truths of finding parents and siblings through DNA | Author interview by Martha Vickery (Fall 2020 issue)

Together at Last: Stories of Adoption and Reunion in the Age of DNA is a collection of 38 stories written by people who found lost family members that they wondered about for many years or never knew they had, through the power of science and the internet.

But, Together at Last is not about science or technology, rather, it is about love, joy, loss, sadness and human connection, in short, everything that families are made of. The collection was assembled by a team of talented editors and volunteers from 325KAMRA, an organization founded by several half-Korean adoptees (whose fathers were U.S. servicemen stationed in Korea, and whose mothers were Korean). The stories are by people who 325KAMRA helped, through its small network of what they call “search angels” —- people who help adoptees find their families.

Most, but not all of the writers are Korean adoptees; one is not an adoptee at all. Their stories are very different from one another. The technology of genome mapping, the internet and the dogged persistence of the searchers are the common elements of these stories of finding lost (or brand new) family members.

In 2015, a few adoptees who found U.S. fathers or fathers’ families through DNA matching told their stories at a Berkeley, California conference entitled Koreans and Camptowns, sponsored by the tour and search organization Me and Korea. Those who told their stories were immediately inundated with questions and requests for help from participants, and soon decided form an organization that could help Korean adoptees navigate the new world of DNA matching. Soon the new organization, 325KAMRA, had a website, some expert DNA advisors, and a small team to help with searches.

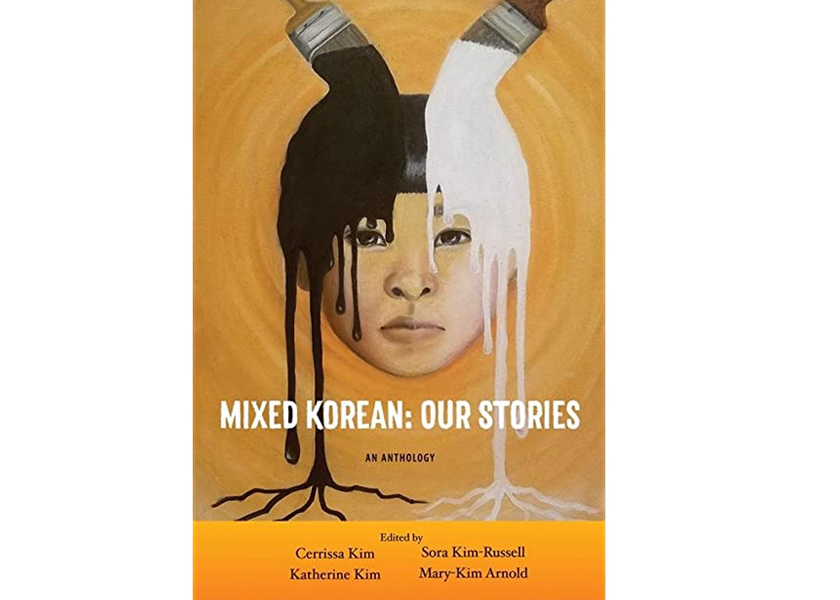

In 2018, 325KAMRA (the acronym is for Korean Adoptees Making Reunions Attainable) published its first collection of stories, entitled Mixed Korean: Our Stories, a collection of stories from adoptees and non-adoptees about the challenges of being mixed race in the U.S. and in Korea.

The new Together at Last anthology was edited by a team of six; five editors and a graphic designer, headed up by Paul Lee Cannon, a journalist and editorial project manager. Cannon is not an adoptee; he met the group when he submitted a story for Mixed Korean. That group did promotional reading events together occasionally in 2019 and “became a real tribe,” he said.

Thomas Park Clement, a half-Korean adoptee, paid to publish the book through his philanthropic Thomas and Won Soon Foundation. Clement, a self-employed medical device inventor, has also worked with 325KAMRA for a few years to supply $1 million in DNA test kits to any Korean adoptee who requests one, and has sponsored distribution of test kits among birth mothers in South Korea.

Clement submitted his own story to the anthology, about how he located information about his deceased birth father, and connected with a half-sister. Interestingly, after working hard on making sure adoptees were able to find and meet their birth families, Clement said he had no desire to meet his U.S. birth family or go further with his search. “I want my friends to find whatever they are searching for in this life,” he wrote, “and am willing to help them, but I am content.”

The stories had all been gathered and submitted by March, Cannon said. It was a gift to have an absorbing project to do at home while sheltering in place. The writers were “very thankful, very amenable to edits, and just really eager to share their story. As much as they were excited to be reunited with birth family, they were just as excited to share that story with the world, and to have a platform to do that.”

DNA testing causes surprises and upheavals in peoples’ lives, both good and bad. “These stories are definitely a reflection of that, for sure,” he said. “Not every story is a triumph. There’s a lot of tragedy and heartbreak, and not having complete closure. A reunion is an ending and a beginning. …there’s a ‘to be continued’ aspect of each of the stories, and that’s part of the magic of it,” Cannon said.

Licensed marriage and family therapist Robyn Joy Park reflects on the importance of DNA in family reunion with her own story in the prologue. In 2007, she reunited with a woman she presumed to be her birth mother, along with a presumed birth brother. Her story describes the close and joyful relationship they developed. In 2012, through DNA testing, she discovered that the woman was not her biological mother. She had the responsibility to break the news. As a therapist, Park writes, that she has reflected about how post-adoption services should be adapted to use latest and best practices, such as “including DNA testing in the process of family reunification to ensure it is a match before reuniting individuals.”

Tim Thornton of Olympia, Washington submitted his story, on how he met five sisters through DNA matching. His father, who was stationed in Korea with the military, got married after he returned from Korea. His father died about six years before Tim located him. The siblings he connected with are convinced their dad knew nothing about Tim.

Thornton said in an interview that his desire to do a DNA search was prompted by wanting to know more about his birth mother. “Although I always told myself I didn’t care, because I didn’t think there was any hope to find any information about my family.” Once or twice, he said, he had tried and failed to contact the people who ran the orphanage, Seoul Sanitarium and Hospital, where he was placed.

Eventually, when Thornton and his wife Sandy went to Seoul in 2016, they located the medical center that was attached to the now-closed orphanage. Surprisingly they had his records in the archives, in fact 130 pages worth, digitized, that they copied to a flash drive and gave to him on the spot. A note in the records included his birth mother’s name and address at the time. This story is to be continued. The Thorntons want to follow up on this information when they go back to Korea as soon as the pandemic allows, probably in spring 2021.

Putting DNA on the record can give people results they did not expect. In Thornton’s case, his dad had to be one of two brothers who both spent time in Korea. Through a nephew whose DNA was listed, his search eventually turned up the nephew’s mother, his half-sister Michele, and four other sisters, with husbands and families, in New Hampshire. He also eventually met cousins, his father’s sister, and his father’s second wife.

Thornton met the family in New Hampshire. With no brother in the family, after some initial shyness, the sisters talked about how much Thornton looked like their dad Robert Bennet. They marveled over how his nose matched their noses, and how his hands looked like their dad’s, and how his and his dad’s voices sounded alike. His story describes the initial awkwardness in meeting the family melted away, with all feeling a sense of acceptance and joy.

The Bennet siblings have a group chat frequently now, Thornton said, and he is slowly getting to know them. “My adopted family will always be my family,” he wrote at the end of his story. “So I feel blessed to be part of two wonderful families. Someday I hope to find my birth mother and her family, and then I will have three families.”

Maria Johansson, a Swedish Korean adoptee, submitted a story Three Branches Belonging to the Same Tree, about how, through DNA testing, she met with her half-brother Henrik who had also been adopted to Sweden, and how together they were contacted by their half-sister Lindsey, who had grown up in Madison, Wisconsin. Maria and Henrik formed a close relationship, but the two have only met with Lindsey once in person at an adoptee event in Stockholm. The three have stayed in touch.

Johansson said she got mixed messages from her family members about finding Henrik. “I was very happy about our discovery. …I wanted to celebrate with my closest relatives and get their support.” But she found that family seemed awkwardly silent. Even her dad, who is now single, did not say anything supportive, which was disappointing, she said. “Maybe it was a shock to him too.”

Henrik had a similar experience with his adoptive mother, a widow, except she was very honest about her feelings. “She was afraid to lose Henrik,” Maria said, even though she realized the idea was illogical.

Maria and Henrik were both enthusiastic, and they quickly bonded. “Both Henrik and I are very curious people, and it should not be much of a surprise to either my dad or Henrik’s mother that we would want to search,” she said.

After Lindsey found Henrik and Maria, she also found a link to their birth mother through finding her birth father (not the same birth father as Henrik or Maria). A March 2020 DNA test confirmed Lindsey’s match with the woman thought to be her birth mother; this means that the same woman is also Henrik and Maria’s birth mother. As the story ends, there is a “to be continued” quality to this story too. If their birth mother agrees, and things work out, the three may meet their birthmother in 2021, but not all together. Lindsey will be on a tour with other adoptees. Maria and Henrik will visit together later on in the year.

According to Cannon, the book promotion plan is still up in the air. It only recently went to the printer. “I have to sit back and think a bit on how that is going to work,” Cannon said, “because of the pandemic, I would love to coordinate public readings …I’ve thought about using Zoom but that might be just too logistically challenging!” Just as nobody knows what the work and social environment will be by mid-2021, it is difficult to pre-plan for events at this point too, he said.

Editing stories for this anthology, Cannon said, as a non-adoptee, taught him a lot about issues faced by Korean adoptees. “All the writers have this incredible resilience, which shows in their stories, and it is very inspiring. They for the most part, have really good lives, but they have this struggle that they’ve had to carry with them through their lives. And I honor that.”

In all the stories, Cannon said, these family seekers had in common one moment, “when an adoptee saw their birth family, the reaction was ‘wow, for the first time, I’m seeing somebody who looks like me,’” he said. “As a non-adoptee, that was incredibly profound,” he said. “As human beings, that’s instinct. That’s what we naturally need. And that’s what drives the adoptee journeys.”

Together at Last is now available on the 325KAMRA website, at: www.325kamra.org