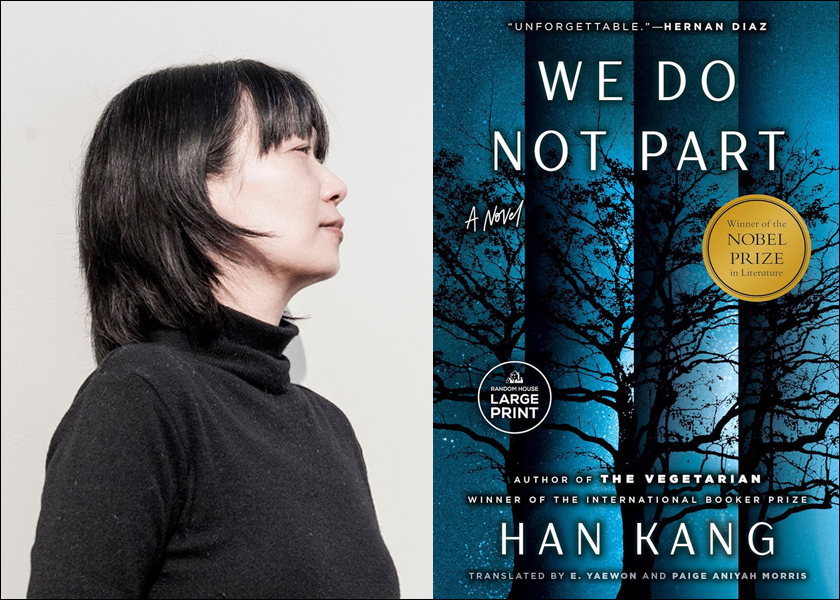

We Do Not Part ~ By Han Kang, with e. yaewon and Paige Aniyah Morris, trans.

In We Do Not Part, Han Kang describes how violence reverberates to the present in those who discover and describe history

(Hogarth Press, New York, 2025, ISBN # 978-0-5935-9545-9)

Review by Alice Stephens (Spring 2025)

In We Do Not Part by Han Kang, Kyungha, an author, is haunted by a novel she has written about a massacre in a South Korean city. She suffers recurring nightmares of a snowy graveyard of dead tree trunks and earth mounds which become inundated by water while she desperately tries to save the bones of the dead.

Paralyzed by the profound effect of writing about such an ugly event of her country’s recent history, her life has stalled. She reflects, “In retrospect, it baffles me. Having decided to write about mass killings and torture, how could I have so naively — brazenly — hoped to soon shirk off the agony of it, to so easily be bereft of its traces?”

Like Kyungha, the author Han Kang, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in literature in 2024, has written a novel depicting the 1980 Gwangju massacre, when hundreds were killed during an uprising against martial law declared by the military dictator Doo-hwan Chun. Kang published that novel about the reverberations of the massacre, Human Acts, in 2014.

We Do Not Part takes the story of the legacy of such violence a step further; it is about the toll such storytelling takes on those who have stared into the horrors of history, and the eternal battle between remembering and forgetting.

The plot is simple: Kyungha’s friend, Inseon, has severed two of her fingertips in a woodworking accident at her isolated home in Jeju Island. She is medevacked to a hospital in Seoul, where Kyungha visits her, witnessing the painful needle pricks to Inseon’s re-attached fingertips that must be endured every three minutes to keep the blood flowing so the nerves won’t die, as sensation is necessary to her as a photographer and woodworker.

The two friends met during their carefree youth while on assignment for a magazine. Kyungha and Inseon have been collaborating on an art project that manifests Kyungha’s dark dreams of tree trunks and mounds. Inseon begs Kyungha to leave for Jeju immediately to save the life of her bird, who has been without food and water since she’s been in the hospital. Kyungha boards the next plane to Jeju, and lands in a snowstorm.

In this novel, as in other Han Kang works, nature itself is a character. The story begins in the sweltering heat of summer, when Kyungha is drowning in her dark dreams, her ruined life, the trauma of history that she cannot put out of her mind. The main action of the story unfurls over one dark and snowy night. The snow is relentless, astonishing in its beauty, terrifyingly efficient in its erasure, smothering everything, changing the very mechanics of noise, heavy with the promise of death.

As night encroaches and the snow becomes a blizzard, Kyungha tries to remember the way from the bus stop to Inseon’s rural home. She falls into a streambed and curls up, letting the snow cover her.

I don’t know if this is what happens right before you die. Everything I have ever experienced is made crystalline. Nothing hurts anymore. Hundreds upon thousands of moments glitter in unison, like snowflakes whose elaborate shapes are in full view. How this is possible, I can’t say. My every pain and joy, all my deep-rooted sorrows and loves, shine, not as an amalgam but as a whole comprised of distinct singularities, glowing together as one giant nebula.

Then she thinks of the bird, gets up, and makes her way to Inseon’s house. Or does she?

As the things that happen to Kyungha at Inseon’s house get increasingly bizarre, the reader is left to wonder whether she is a reliable narrator, or whether she has crossed over into insanity, or death.

Kyungha carefully protects her own past. While there is mention of a possibly estranged daughter, there is no reference to parents, a husband, a childhood, or any exterior life other than the book she wrote about the Gwangju massacre and her relationship with Inseon.

Meanwhile, in Kyungha’s recalled conversations with Inseon and in excerpts from documentaries Inseon has directed, Inseon reveals the harrowing history of her parents and other relatives whose lives were warped by another massacre, the violent response to a 1948 uprising in Jeju against a divided Korea that led to the brutal persecution and killings of 30,000 to 60,000 people, estimated as 20 percent or more of Jeju’s population, by Korean government troops in collaboration with the U.S.

Without the use of punctuation, and with the overlapping timelines and circumstances of Inseon’s monologues, the reader must take care to piece together the narrative, mimicking the sifting and organizing of information that a writer like Kyungha or filmmaker like Inseon does when researching and producing a documentary work of history.

The translation, by e. yaewon and Paige Aniyah Morris, captures the elegance of Kang’s prose and careful precision in tone, neither too overwrought to match the profound trauma of the related events, nor so detached that the reader doesn’t care for Kyungha’s and Inseon’s fates. There are copious descriptions of snow that conjure the beauty, wonder, and menace of a precipitation that hovers in the liminal space between ice and water, just as Koreans, and indeed all humanity, live in a state of forgetting and remembering.

Sometimes remembering can be nothing more than a covering up of the truth, so that the actual events are mere suggestive contours under a thick, dazzling layer of evasion and revisionism. This kind of willful forgetting has immense consequences, demonstrated by the recent removal of South Korean President Suk Yeol Yoon after his failed attempt to impose martial law under the flimsiest of pretexts. Kang’s traumatized protagonist takes the opposite extreme in relating the past; she looks honestly and unflinchingly into historical truth, but it is accomplished at her own peril.

With only five of Han Kang’s books available in English translation, Anglophone readers will be eagerly awaiting more of her works (see KQ’s review of Han Kang’s The White Book). Kang writes of Korean characters in Korean settings, and although in Human Acts and We Do Not Part she addresses pivotal moments in modern Korean history, her writing does not belong to South Korea alone. Her stories transcend time and place to speak to the very truths of humanity and the struggle to understand the evil that is done in our name.