Rise: A Pop History of Asian America from the Nineties to Now ~ By Jeff Yang, Phil Yu and Philip Wang

Compendium chronicles the emergence of pan-Asian influence in the American mainstream

(Mariner Books, New York, 2022, ISBN #978-0-358-50809-0)

Review by Joan Thompson (Spring 2025)

Encyclopedic in its scope, Jeff Yang, Phil, Yu, and Philip Wang’s Rise addresses Asian American popular culture over the past three decades. Divided into five sections, Before, 1990s. 2000s. 2010s, and Beyond, the book looks not only at popular culture, but also at news events and noteworthy Asian Americans associated with these decades. This compendium includes articles on many topics: Food, film, literature, music, television/media and the internet

Each of the three main author introduces one of the three sections. Jeff Yang, one of the founders of A Magazine, introduces the 1990s, while Phil Yu, founder of the Angry Asian Man blog, introduces the 2000s. The 2010s are introduced by Philip Wang, co-founder of Wong Fu Productions. Each introductory essay gives an overview of the decade but with a personal perspective in exploring each writer’s memories and experiences.

Each section includes articles that parallel and update each other, for example The Asian American Syllabus, The Style List, The Asian American Yearbook, Founding Fathers and Mothers, and Undercover Asians. Each section also includes content specific to the time period, including interviews and essays by other writers.

In the essay Before, Jeff Yang looks at the origin of the term “Asian American,” which has shifted in meaning in the decades since it first emerged. Yang, who claims he was born the same year as the term “Asian American,” looks at the way college influenced his idea of being Asian American. His essay introducing the ‘90s looks at his work at A Magazine and Village Voice during the years when there were protests outside Miss Saigon performances, and when the LA riots occurred. During the same era, a shift happened in the overall anti-Asian sentiment: it was directed at the Japanese during the ‘80s, and changed to the Chinese in the ‘90s.

Among the pieces in this section is Sa-I-Gu 1992, focusing on an interview of Eurie Chung and Grace Lee, documentarians of the uprising of the Black community in Los Angeles after the four white police officers were acquitted of the (videoed) beating of an African American, Rodney King, after a traffic stop in Los Angeles. The uprising was also directed (or misdirected) to business owners in Koreatown, whose shops were looted and burned down.

SuChin Pak looks at the way in which Connie Chung, who became a news anchor in 1993, inspired her to seek a career in broadcast journalism. An essay by Brian Hu looks at the rise of full-length indie films by Asian Americans in the 90s.

Phil Yu discusses the way in which 9/11 and the violence against South Asians that followed made him reconsider who the term Asian American encompasses. The section encompassing the early 2000s also includes an article on the growth of Asian American suburbs. Highlights of popular culture during this decade included the growth of Asian American representation in the hip-hop scene, from DJs to dance crews and rappers, including interviews with Jonathan “Dumbfoundead” Park and James “Prohgress” Roh. The growth of social media and the rise of YouTubers, many of whom were Asian American is another focus of this section. The section also profiles of artists who started on Youtube, including video artists such as Joe “Jo” Jitsukawa and Bart Kwan, and musicians including David Choi.

In introducing the 2010s, Philip Wang discusses the shift to Asian American YouTubers doing live concerts, which were promoted by Wong Fu Productions. He also highlights the ways in which new online options such as Instagram led to increased representation by Asian Americans, and more use of internet for entertainment by Asian Americans.

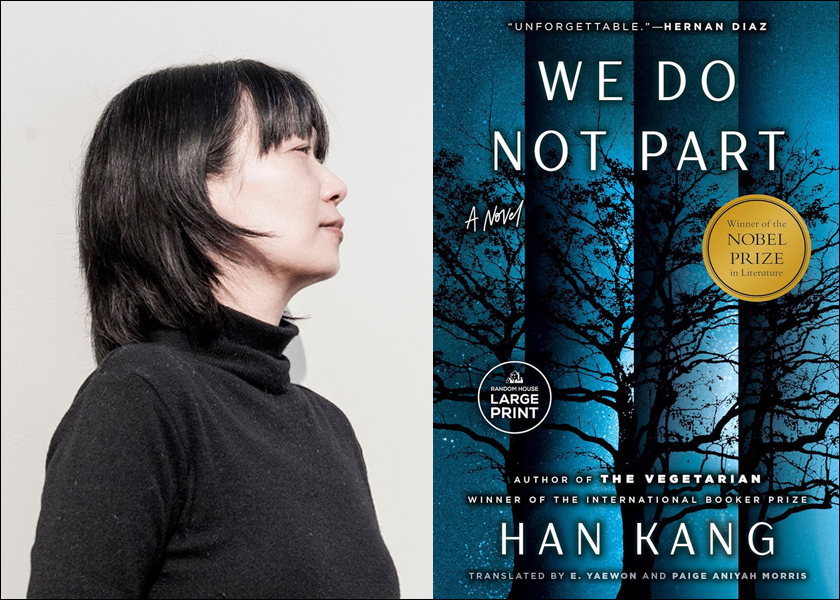

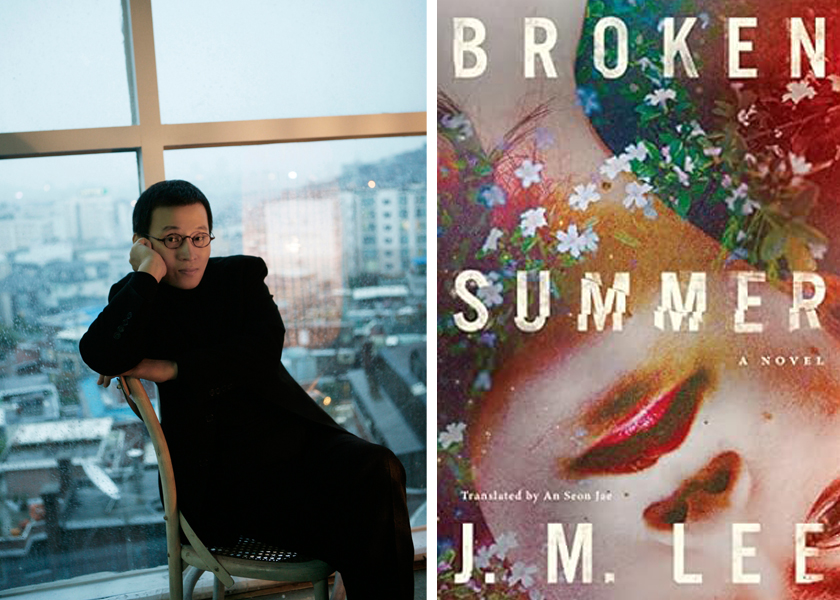

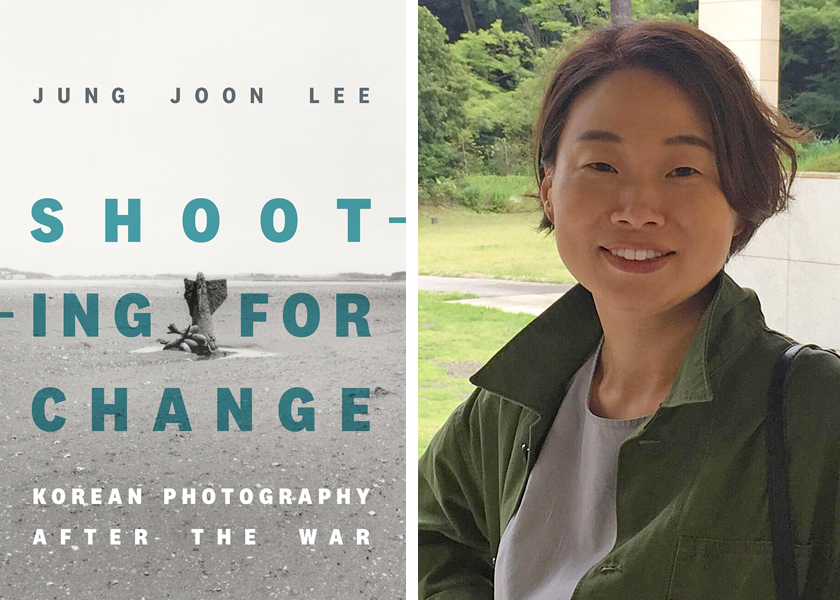

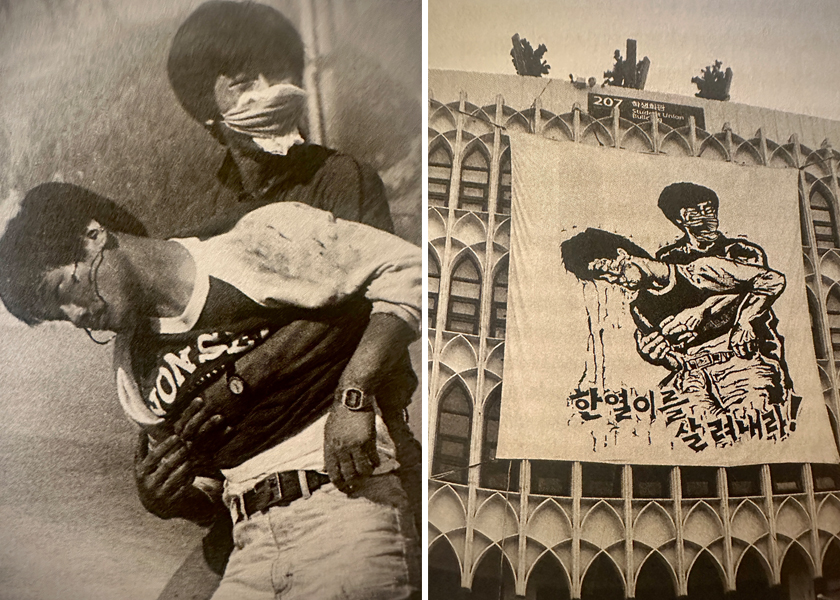

Among the essays in this section are several on the significance of the TV show Fresh off the Boat, and an interview entitled Three Kings focusing on the careers of Daniel Dae Kim, Ken Jeong, and Randall Park. Euny Hong’s essay Hallyu Like Me Know discusses Korean pop culture and its growing importance in the U.S. and elsewhere.

All three writers contribute to the final essay Beyond, written in 2021. They note that they expected to end on a more positive note given the rise in Asian American representation over the past three decades. However, the COVID-19 pandemic and the way in which it was racialized during that time by politicians including Donald Trump led to an increase in violence against Asian Americans, including towards vulnerable elders living in ethnic enclaves.

Yet the writers see an encouraging rise in new activists at the same time. They also celebrate a move by Asian American entrepreneurs to market their products to the countries their families emigrated from as well as the diaspora, citing Roland Ros and Rexy Dorado and their messaging system Kumu, which is now popular with users in the Philippines, the U.S., Canada, and Australia.

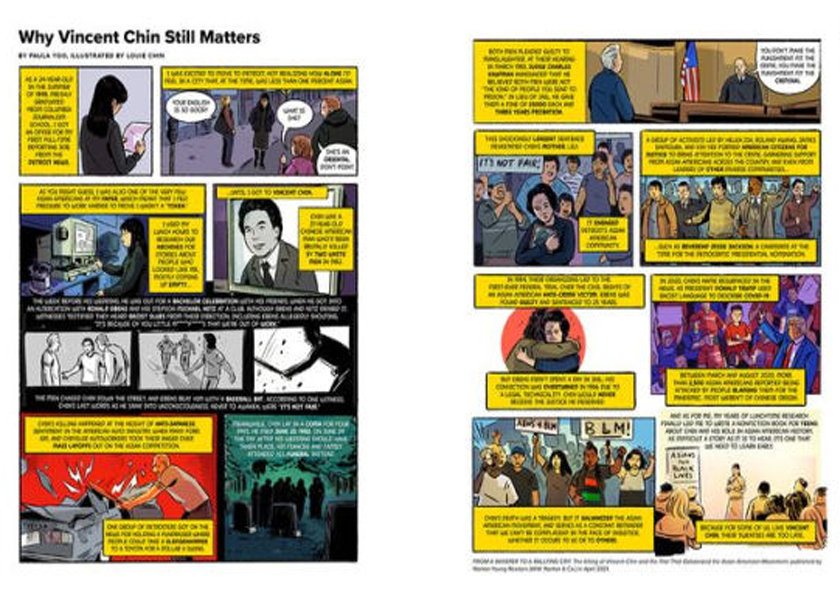

Additonally, Rise provides a visual feast. Each section includes foldouts highlighting Asian American spaces from boba shops to houses of worship tied to Asian religions. Comics appear throughout the book also, ranging from one about South Asians participation in spelling bees to the process leading to the filming of the hit all-Asian film Crazy Rich Asians.

Illustrations by Sojung Kim-McCarthy are included in each section on famous Asian Americans in politics, including one mimicking the famous painting of Washington crossing the Delaware. Another delightful visual scattered throughout is a collection entitled Postcards from Asian America, which gives voice to the everyday experiences of Asian Americans throughout the country.

Rise includes the emergence of Asian American emergence in TV, film, music, food, fashion, literature, gaming and social media. The writers document an Asian American presence so central to the U.S., that every reader is sure to discover a film or TV show they missed, new music to listen to, or a graphic novel that speaks to them.