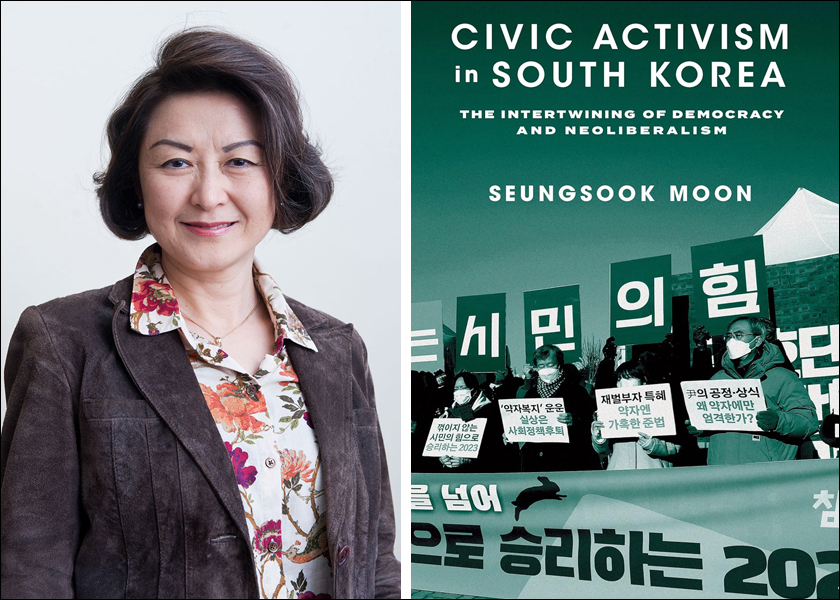

Civic Activism in South Korea: The Intertwining of Democracy and Neoliberalism ~ By Seungsook Moon

(Columbia University Press, New York, 2024, ISBN #978-0-2312-1149-9)

Review by John Feffer (Winter 2025)

In the late 1990s, at the request of five South Korean organizations, I put together a conflict resolution training program in Seoul. The groups were interested in learning more about nonviolent ways of resolving disputes in the community, at a national level, and across borders. Another aim of the program was to explore ways for peace activists to learn professional skills and create sustainable livelihoods for themselves.

It was a pivotal stage in South Korean democracy. The people power that had forced the Tae-Woo Roh government to usher in elections in 1987 had given way to a new set of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) devoted to expanding and deepening the fledgling democracy. People’s movements (minjung undong) continued to operate throughout the country, relying on volunteer organizers and often ad hoc actions. But increasingly, the political space was dominated by civic groups (simin tanche) that employed staff, engaged in fundraising, and tried to expand membership through sustained programming. The late 1990s, according to survey data, was the moment of peak influence for such citizens organizations.

Although movements played a critical role in the political life of South Korea, the movement life was a difficult one. It was fine for young people who didn’t need much money. But as activists got older, got married, and had children, a life of unpaid protest became increasingly unsustainable. To turn activism into a profession was one of the goals of our conflict resolution training program — as well as to think about how to turn negatively framed campaigns of protest into positively framed programs of action.

The tension between the more radical and spontaneous movements and the more bureaucratically organized and professional organizations has continued in South Korea. Today, the NGO space is rich, diverse, and well-connected, with organizations devoted to the environment, women’s issues, immigrants, government transparency, and so on. But social movements have continued to mobilize the energy of different constituencies, particularly young people, on critical issues, for instance around food safety during the 2008 beef protests or the more recent protests that led to the impeachment of Suk-yeol Yoon.

In her new book Civic Activism in South Korea, Seungsook Moon looks at this tension between movements and NGOs through an economic lens. She argues that South Korea, across different political administrations, adopted a neoliberal approach to the economy, and this has necessarily influenced the political life of the country. Neoliberal policies — promoting market solutions, putting the onus on individual rather than collective action, pushing NGOs to undertake services that the government might otherwise provide — have all established the rules of the game by which everyone must play.

Moon tells her story through the experiences of three groups: People’s Solidarity for Participatory Democracy (PSPD), Democratic Friends Society (DFS), and Friends of Asia (FOA). Devoted to promoting transparency and accountability in government and the business world, PSPD was one of the first prominent South Korean NGOs (and one of the five groups participating in our conflict resolution training program). DFS focused more on the empowerment of women. And FOA was a volunteer effort to help foreign migrants adjust to Korean society.

Through these three organizations, Moon shows how neoliberal values shaped, constrained, and changed the trajectory of civic politics. Even the conflict resolution program I helped create in South Korea was part of this neoliberal turn because of its goal of providing activists with professional skills.

“Not all advocacy organizations supported neoliberalism or functioned as its tool, but there is an elective affinity between the professionalization of activism and neoliberal governance,” she writes. In effect, neoliberal governance needed paid NGO staff to undertake tasks that the government couldn’t or wouldn’t perform. This was not just a cost-saving maneuver. It also potentially prevented under- or unserved communities from rising up in anger to unseat the government.

PSPD is emblematic of the challenges that NGOs faced in that first decade of democratization. To effect change in government behavior, PSPD had to engage with and lobby public officials. When progressives took over the national government, PSPD worked with them closely on social welfare issues, though it frequently took contrary positions on foreign policy. At the same time, PSPD also wanted to retain some aspects of a movement organization by encouraging grassroots participation. When that participation began to wane, PSPD had to address more seriously the criticism that it was a “citizens’ movement without citizens.”

The other two organizations faced similar challenges. DFS established coops that provided healthy food. These coops proved so popular that they overshadowed DFS’s original goals of feminist social change. Because it received funding from the government to provide social services, it also ended up supporting a key neoliberal principle of privatizing state functions. FOA, meanwhile, didn’t take government funds and thus relied on volunteers, for instance, to teach Korean to immigrants. But without consistent sources of funding, it was hard for FOA to maintain its activities and its volunteer staff.

Moon points out, quite correctly, that even progressive administrations in Korea pushed certain neoliberal policies, such as the deregulation of financial services, the flexibilization of labor, and the establishment of free trade agreements. Given this policy environment, it was very difficult for any NGO that hoped to influence government actions not to “play the game.” Or, as Moon puts it in the context of PSPD: It “appropriate[d] neoliberal governance by reinterpreting it as democratic governance; this appropriation is tolerated as long as its activism does not seriously threaten the core logic and practices of neoliberalism.”

It has thus been the responsibility of more radical movements, with little experience of engaging with this type of “democratic governance” and unseduced by funding provided by national and local government agencies, to challenge the neoliberal logic through, for instance, the protests against the free trade agreements that the Moo Hyun Rho administration supported.

Although she recognizes the limitations of such movement politics — inconsistency, disorganization — Moon tends to valorize such activism because of its refusal to obey neo-liberal dictates. But this kind of dichotomizing is possible largely because of the way Moon defines neoliberalism as an all-encompassing analytical category. To be sure, neoliberalism is a powerful ideology in the way that it has influenced policy across the political spectrum. But neoliberalism is only one form of capitalism, not capitalism itself. And many of the criticisms she levels against Korean NGOs could apply to NGOs functioning under different forms of political economy.

Take, for example, the professionalization of activism. This was a challenge in modern societies prior to the rise of neoliberalism in the 1980s, though of course the need to earn money takes on a slightly different meaning under current market conditions. Social work, as one field of professional activism, existed before the deregulation of the state (indeed, before the creation of the welfare state). PSPD was not just conjured into existence by the spread of “neoliberal globalization,” as Moon asserts. It drew inspiration from an earlier generation of activists like Ralph Nader, who pioneered the holding to account of corporations and government prior to the rise of the neoliberal state.

This is not just an analytical criticism. The challenges that Korean activists face derive not just from the specific nature of Korea’s current form of political economy. Activists must struggle with the issue of professionalization in social democracies as well. The relative balance of state versus non-state social services is going to be a question even in countries that eschew the market. And the accountability of institutions is an essential issue in modern societies, whatever their political economies.

As such, the imagining of alternatives outside the neoliberal frame must also take into account the dynamics of different varieties of capitalism, the imperative of economic growth associated with industrialization, and the evolving nature of modernization more generally. As political parties — and even institutions like the World Bank — begin to recognize the shortcomings of neoliberalism, activists, too, have an opportunity in South Korea and elsewhere to explore new ways of thinking about political economy. This is a potentially liberating moment, but activists will discover that many of the challenges of the neoliberal era will not wither away because they are, to a certain extent, independent of neoliberalism.

Despite these minor criticisms, Civic Activism in South Korea is a valuable text on the transformation of civil society in a modern, globally connected democracy. Korean civil society has proven remarkably vibrant across half a century. The tensions between the more ad hoc movements and the more professional NGOs have ultimately strengthened the country’s social fabric, even under the corrosive influence of neoliberal economic policies. Activists and analysts across the world can learn much from the Korean experience, which Moon’s book so trenchantly describes.