A decade after the historic 2015 DMZ crossing, peace activists gather to remember in South Korea | By Iris Yi Youn Kim (Summer 2025)

On an overcast Saturday in May, hundreds of people gathered at the Naeri Cultural Park just outside of the U.S. Army Garrison (Camp) Humphreys in Pyeongtaek, South Korea.

The group was gathered to commemorate an event held 10 years ago, the 2015 crossing between North and South Korea by women peace activists from many countries, created and organized by the American peace activist organization Women Cross DMZ.

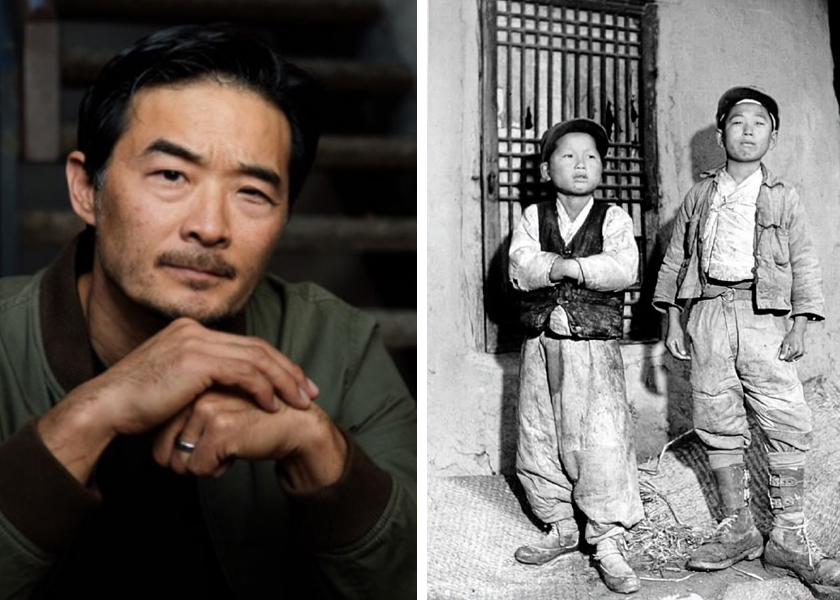

Participating in the march was Korean American organizer Jean Chung, who in 2015 joined the crossing of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), the militarized border area between South Korea and North Korea.

The 2015 crossing, led by Korean American peace activist Christine Ahn, brought together a delegation of 30 international feminist peacemakers including Nobel Peace Prize laureates Leymah Gbowee and Mairead Maguire. The purpose of the DMZ crossing was to call for a permanent peace agreement and an end to the Korean War.

Chung recalled the scale and the historic nature of the march, which began in North Korea and involved women from various cities. “We walked with 5,000 North Korean women in Pyongyang and Kaesong, then marched again with the Kaesong women when we crossed the border, where more than 5,000 South Korean women joined,” she said. “It was a massive, memorable event.”

Now that 10 years have passed, Chung said, the 2025 march still stands as a crucial reminder of the urgent need for peace on the Korean peninsula. “Ten years later, the situation is worse: North Korea and South Korea treat each other like adversaries, and North Korea just declared that South Korea is not a Korean nation,” she said.

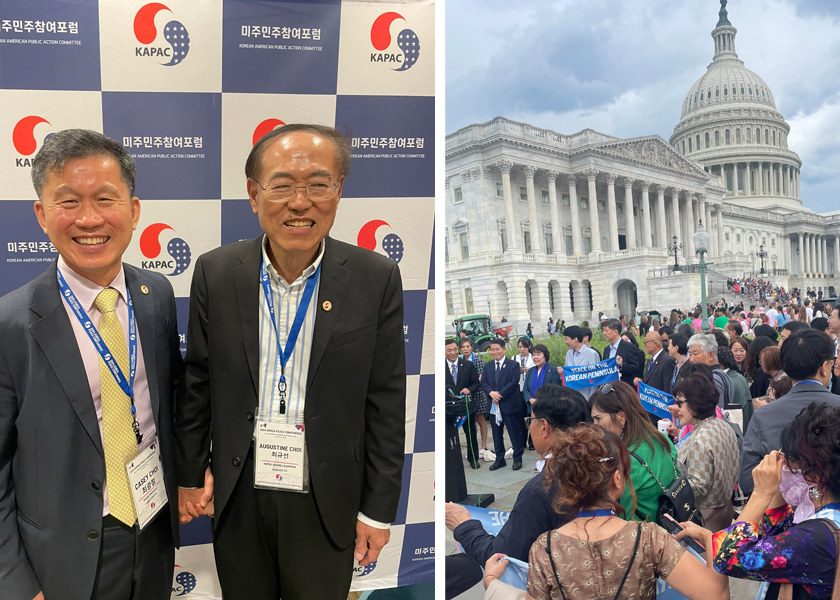

The 10th anniversary march was a collaboration between Women Cross DMZ, the organization Ahn established to accomplish the 2015 crossing, the Gyeong-gi Women’s Organization, and other Korean women’s peace organizations. Women Cross DMZ’s current executive director, Cathi Choi, honored the spirit of the 2015 crossing by inviting a delegation of six international peacemakers to join the May 2025 march.

“My intention in bringing this delegation was to continue building power and political will in the United States and fuel the next generation of anti-war organizing,” Choi said. “We need to ensure that we understand the role that the Korean War plays in propping up the U.S. military.”

The state of a peace resolution in the Korean peninsula

Eleven years ago, when Ahn began to organize and raise funding for the 2015 DMZ crossing, the delegation put together a list of demands that included an end to the Korean War through a permanent peace treaty, the reunification of Korean families, the lifting of sanctions, and the amplification of women’s involvement in the peacebuilding process.

Chung said that, at the time, activists perceived that the exclusion of civilians and women in peace negotiations had been stalling any progress. “Because ordinary people in North and South Korea were not able to culturally exchange or meet, the reconciliation was taking a step forward and then moving further back,” she said.

Then-South Korean president Geun-hye Park had presented a publicly positive, but privately ambiguous front towards peacemaking prospects. As the peace delegation approached the day of the crossing, it faced hostility from both the South Korean government and the media. Before Ahn could continue with the march, she was forced by the South Korean government to sign onto a statement that she would not violate a 1940’s National Security Law which prohibits actions or speech that support any of North Korea’s positions. The group was also forced to reroute the DMZ crossing from Panmunjom, where the 1953 armistice was signed, to a trade checkpoint in the North Korean town of Kaesong. Instead of marching across the DMZ from north to south, they had to make the crossing by bus.

The current political views concerning peace on the Korean peninsula are up in the air. After former President Suk Yeol Yoon’s impeachment in April 2025 and this month’s snap election of a new president, Jae Myung Lee, there are conflicting signals from the administration about opening up peace talks with North Korea while bolstering a military relationship with the U.S. and Japan. Officials under President Trump have quietly explored resuming peace talks with North Korea.

Choi said that the political landscape between the U.S. and Korea has shifted considerably over a 10-year period. “In the past few months alone we saw drastic changes in South Korea’s political landscape with impeachment and the election,” Choi said. “We’ve seen multiple successive administrations start and stop talks with North Korea.”

The organization, too, has been steadily building momentum with its advocacy. Since Ahn founded Women Cross DMZ in 2014, the group has spearheaded the Korea Peace Now grassroots network — a global coalition of women’s peace organizations. Korea Peace Now has pushed forward several House bills calling for a permanent peace resolution. In 2024, H.R. 1369 signed on 53 co-sponsors.

“Ten years ago, this was a network that didn’t exist. We have veterans, civic society activists, and everyday people who are learning how to advocate for policy and change the narrative on the Korean War,” Choi said.

Marching towards hope

The May 2025 peace walk began on a trail just outside of Camp Humphreys and was planned to cover about a three mile section of the military installation’s wide perimeter. As the group of 300 made its way towards the garrison, the razor wire fence and “No Photography” signs loomed just next to the pathway.

Jung-A Lee, a representative of the Gyeong-gi Women’s Association, said that women’s groups had been gathering here every year since the 2015 crossing. “The 2015 crossing created a space for us to ask ourselves, what is the voice of women in Gyeonggi-do to advance peace? We found that there were almost no campaigns focused on helping women, even though 34 percent of North Korean defectors live in the Gyeonggi district, and 88 percent of them are women,” she said.

The association continued the women’s peace walk in Pyeongtaek annually on May 24, the International Women’s Day for Peace and Disarmament. They began collecting the stories of defectors, women farmers in the DMZ, and camptown workers to demonstrate the effects of war on women. They founded the annual Gyeonggi Women’s Peace Forum in 2019.

“The DMZ is a boundary that divides north from south, but divides men and women, minorities, and regions,” Lee said. “This annual walk is the least we can do.” As the peace walk participants found their way back to the Naeri Cultural Park meeting point, Chung reflected that there will be little political will for peace between North and South until the restrictions on communication and travel between the two states are relaxed and various kinds of people-to-people diplomacy can resume.

“The role of women is more critical than ever before — with women it is more possible to have horizontal communication, rather than leaning on hierarchy and bureaucracy,” Chung said. “That’s why we are walking today, in order to refresh our resolution for building peace and reconciliation.”