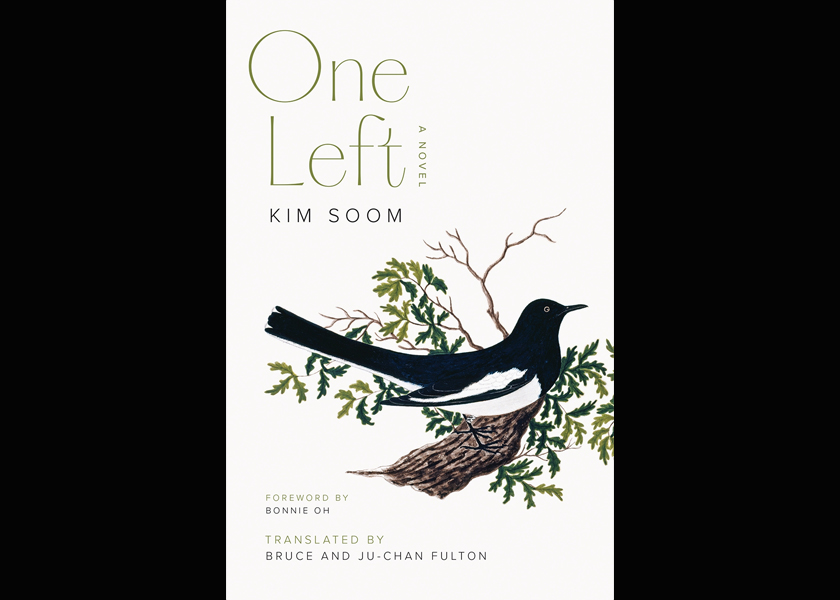

One Left: A novel ~ By Soom Kim (translated by Ju-chan and Bruce Fulton)

(University of Washington Press, Seattle, 2020, ISBN #978-0-29574766-8)

Review by Bill Drucker (Spring 2023)

As the old woman folds her blanket, she hears on the television that the last one has passed. An onni – sister, a comfort woman. “No,” the old woman mutters. “There is still me.” She cleans her room and walks out to the veranda. She sees a dead magpie next to her shoes, a gift from her cat, Nabi.

So begins a fictional story that describes a very real group of war survivors. One Left is a beautifully-written novel, dedicated to the Korean women who were forcibly drafted into and survived military sexual slavery by the Japanese Imperial Army in the World War II era. The story has emotional honesty and gravitas, and can be a hard read at time. After just a few chapters, the reader may have to pause. The narrative tugs at our hearts.

The quiet, low-key story begins with the description of an old woman who lives in squalor in a depressed neighborhood. The woman had lived in a tiny apartment for the last five years where her nephew had placed her. Her nephew’s motive is to have an address in an area he believes will get renovated and be more valuable in the near future.

Her self-isolation is due, in part, to the fact that she is afraid of her own past as a so-called “comfort woman,” or military sex slave. Kidnapped at age 13 by the Japanese military, she survived and went back to Korea after seven years to an unwelcoming family and country. The TV news of the death of the woman assumed to be the last onni makes her want to speak the words “I was a victim too.”

The scenario is realistic, as only a few hundred women in South Korea came forward starting in 1991 to publicly tell their stories of the war crimes committed against them. Many became activists for the cause. The total number of Korean women who were forced into sexual slavery is estimated at 170,000 to 200,000; only a fraction of that number survived. Due to the shame of publicly admitting even forced prostitution, it was always understood by the comfort women’s activist movement that there must be hundreds of survivors who remained anonymous.

Magpies figure into the story. In the West, the magpie is a harbinger of bad news. In Korean culture, it is a national bird, the bearer of good news and luck. In Korea, magpie songs can mean that guests or good news will arrive soon.

In the story, the woman’s cat drags a dead magpie to her door, leaving her anxious about what it could mean. The stray cat’s name is Nabi, Korean for “butterfly.” The butterfly is the symbol for the global human rights and justice movement of the former comfort women and their supporters.

In actuality, there are less than a dozen declared former comfort women alive today in South Korea. These elderly women have been dying at a faster pace as the years pass. However, the awareness of the global human rights campaign of the former comfort women is alive and growing today, due to the reach of the internet and the many women’s rights and human rights activists who have taken up the cause.

Their campaign, which began in 1991 and extends to the present day, is to demand justice and reparations from the Japanese for their war crimes against them, including educating the next generation in Japan about the true war history, which is sanitized in Japanese culture. The movement also supports other movements to support women in war.

One Left is Soom Kim’s first novel that has been translated into English. She is a prize-winning writer of nine novels and six collections of short stories. The book is well-researched, with interviews of the actual comfort women, and reviews of the records compilations. Award-winning translators Bruce and Ju-Chan Fulton are familiar names, with their fluid translations of literary works from Korean to English.

In this a telling of a tragic history from the perspective of one elderly former sex slave who sees herself as “the last one,” Kim revitalizes energy for this irreconcilable injustice in a new generation of readers.