“Brain rot” resulting from the haphazard consumption of online media | By Nam-ku Jeong (Fall 2024)

The botched insurrection orchestrated by Korean President Suk-yeol Yoon on December 3 is shocking in several respects.

Yoon had the horrific ambition of mobilizing the army to round up all the politicians who defied him, to paralyze the National Assembly and to muzzle the press, concentrating all power into his hands. His belief that the ruling party’s crushing defeat in the parliamentary elections last April was the result of election-rigging and his conceit of justifying an insurrection by prying open the National Election Commission’s computer systems is absurd to a pitiful degree.

The word of the year, according to Oxford University Press, is “brain rot,” defined as the mental deterioration resulting from the haphazard consumption of online media. I doubt a better example of brain rot than Yoon will be found for a long time to come.

The Korean people’s democratic capacity may have failed to keep the Yoon administration from running the economy, and people’s standard of living, into the ground, but Koreans did put an immediate stop to this insurrection. That’s a strength they have cultivated through decades of bloodshed.

Records of the Joint People’s Association — throngs of ordinary people including rice vendors, butchers, entertainers and shoe menders who gathered by the thousands and the tens of thousands to Jongno, Seoul, in the winter of 1898 and demanded the establishment of a parliament for 42 days on end — are thrilling to read, even today.

That association was the dynamo behind the March 1 Movement in 1919, when Koreans around the country demanded independence from the Japanese, with more than a thousand martyred for the cause. That movement bore fruit in the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea, which was grounded in democratic republicanism.

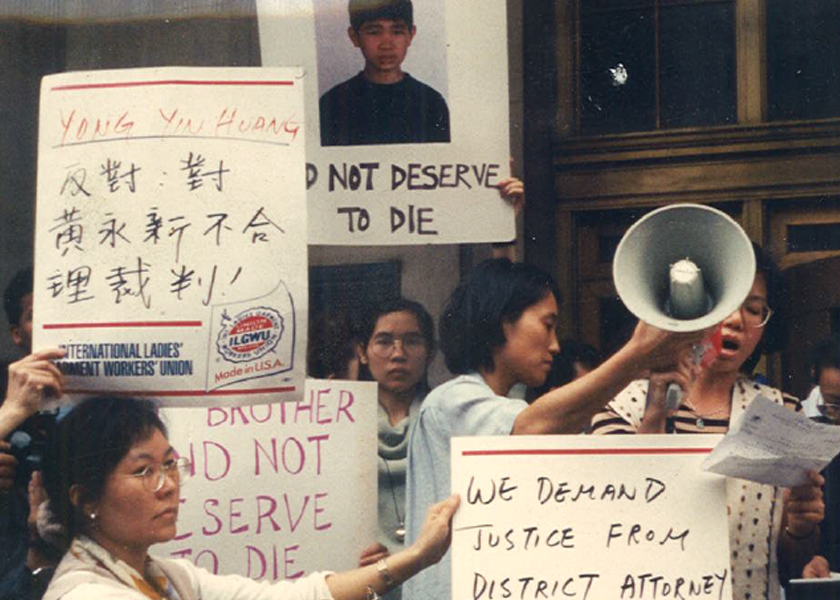

Following Korea’s liberation from Japanese rule, Koreans have reclaimed popular sovereignty from the clutches of tyrants at several key moments, including the April Revolution in 1960, the Gwangju Uprising in 1980, and the June Democratic Struggle in 1987. Whenever leaders have taken the wrong path, their error has been rectified by crowds of candle-bearing protestors.

Once again, this insurrection is being resolved according to the method outlined in the Constitution. The National Assembly has just impeached Yoon; a special counsel will arrest, detail and charge him; and a new administration will be established through democratic elections. In short, the sovereign people will soon triumph.

But despite such heartening reflections, there’s a disturbing aspect of this incident that we must not ignore.

Many have compared Yoon’s insurrection to the coup launched by a military faction under Doo-hwan Chun on Dec. 12, 1979. The two incidents are indeed similar in the sense that enough troops were mobilized to inflict major loss of life.

But the chilling thing about Yoon’s insurrection is that it was a self-coup, in which a legally elected president attempts to install himself as ruler for life. That’s basically what Syngman Rhee did in Busan in 1952, and what Chung-hee Park did with his Yushin constitution in October 1972.

Once again, the people were nearly robbed of their sovereignty by a president they had elected.

In January 2012, as Korea was looking forward to its 18th presidential election, I wrote a column for Hankyoreh newspaper titled “A country that elects kings.”

“We live in a country that elects people who are presidents in name, but kings in fact. Each king is killed (politically speaking) and a new one elected every five years,” I wrote that column.

The notion of “a country that elects kings” comes from “Oriental Despotism: A Comparative Study of Total Power,” by Karl Wittfogel. Wittfogel wrote that choosing kings through elections rather than dynastic succession does not necessarily mean a lesser degree of despotism.

His observation still rings true. We give our presidents too much authority. We are enthralled with the concepts of the “wise king” and the “enlightened despot”; we are so obsessed with “our side” gaining the upper hand that we discount the disadvantages and dangers of the imperial presidential system.

The consequence is a series of failed kings. A president generally comes to power because of the failures of their predecessor, rather than through public support for policies tackling issues facing the community. And then, before long, the president is abandoned by a disappointed public. Problem-solving politics has disappeared, giving way to a fierce struggle for power.

This insurrection came about because the early revelation of Yoon’s failure put him in danger of becoming a lame duck. That drove him to rip off the mask of a president and reveal the face of a tyrant.

That means we’ve wasted nearly three years without addressing fateful issues looming over the country, including our sagging growth potential, polarization and abysmal birth rate.

Obviously, we need a new president. But that alone won’t solve our problems.

Our top priority should be the prosecution service, which has degenerated into a handmaiden of power under the Yoon administration, just like the police under Syngman Rhee and the military under Chung-hee Park and Doo-hwan Chun.

There’s also an urgent need for political reform to ensure that politics reflects the will of the voters through democratic processes.

The Korean people need to wipe the concept of the “wise king” from our minds and amend the Constitution to erect clear boundaries between the three branches of government. Drafting and reviewing the budget should be brought under the supervision and control of the sovereign people.

Given the extreme polarization of the Korean political terrain, that road may look long and rugged, but it’s a road we must take.

The tree of democracy need not be refreshed by the blood of the citizens — but perhaps it does need the blood of kings, from time to time.

The ringleader behind the insurrection and those who played an essential role in that insurrection should be strictly prosecuted under the law; no pardon should be given. That’s the minimum prescription to prevent future presidents from playing king.

(This column, originally appeared in Hankyoreh ~ https://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition )

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]