Lifelong organizer and champion of the movement for peace in Korea | By Christine Hong (Summer 2022)

On March 7, 2022, Hyun-jung Lee, a beloved and deeply-respected comrade in the Korea peace movement, a talented acupuncturist, and a cherished daughter, sister, and emo (aunt, in Korean) passed away after a long and courageous battle with breast cancer.

Just 51 years old, Lee was a bright beacon in the struggle for peace on the Korean peninsula. As Ramsay Liem, curator of the multimedia Korean War exhibit Still Present Pasts, stated, “Each era of the seemingly endless struggle for Korean independence, democracy, and unification has its pillars. Hyun [was] one of ours.”

Goal-oriented to the end, Lee offered video-recorded parting words in late February to fellow organizers, some of whom she had worked with for more than three decades. “I don’t know how far I will make it,” she said while in hospice, “But I feel so confident because we now have an army of people fighting for peace in Korea.” Although ravaged by the cancer that had metastasized to her brain, yet refusing pain medication in order to keep her mind as clear as possible, Lee encouraged her fellow activists, urging us to keep our eyes on the prize of genuine peace. She rallied us “to push together, nobody leading and somebody following — everybody together.”

Not one to clamor for the limelight or be driven by ego, Lee was a people’s organizer, unseduced by the aura around celebrity activists. She led with encouragement, and from below and to the left. Without fuss, drama, or complaint, Lee time and again would roll up her sleeves and do whatever work was required, often behind the scenes. Maximally impactful, yet unassuming, she was a force to be reckoned with. She was an astute strategist and a dedicated workhorse of an organizer for various interrelated causes. She was also a fearless queer woman fighter against racism, sexism, and imperialism whose example inspired generations of activists in diasporic Korean, pan-Asian, and multiracial organizing spaces.

John Won worked closely with Lee in various organizing projects during the 1990s, including Iban/QKNY, a multi-gender queer Korean community group. He noted she was “at the heart of so many movements, as many queer Korean women/femmes have been.” In the broader progressive landscape in New York, Lee belonged to a cohort of radical Asian women organizers who moved the world with an eye to its transformation. Theirs was and continues to be a feminism grounded in praxis.

Lee possessed many gifts. She was a classically-trained cellist, and was educated at an Ivy League university. Despite the many directions her life could have taken, she embraced the work of urban community organizing. After earning an undergraduate degree in English literature from Columbia University, Hyun in 1994 joined CAAAV, an Asian community organization in New York City where she took on the role of a “non-Chinese person training young Chinese immigrants to do street vendor and tenant organizing,” in former executive director Helena Wong’s words.

Lee came of age in a grassroots organization that she would help grow, staying with CAAAV (originally the Committee Against Asian American Violence, now called CAAAV Organizing Asian Communities) until 2004. Indeed, CAAAV credits her as vital to its three-plus decade legacy of “remarkable women who built the base, developed leadership of community members, developed strategic campaigns, coordinated direct actions, showed up in solidarity for others, and built the infrastructure of the organization.”

Gifted at street performances and community art projects, Lee regarded such artistically-driven endeavors as the cultural and educational front of political struggle. “I think Hyun …secretly wanted to be an artist,” Wong stated. With CAAAV youth, she was “always concocting up ideas. …One summer, they decided to do this exhibit where they would take plywood and trace the bodies of the young people on them, and then cut them out and put stories about gentrification in Chinatown.”

Through CAAAV, Lee accrued extensive experience in grassroots campaigning — a skill set that prepared her for the organizing that was the core of her life’s work. She created the Chinatown Justice Project (formerly Racial Justice Project), and initially worked on Korean solidarity for peace and reunification as part of that project.

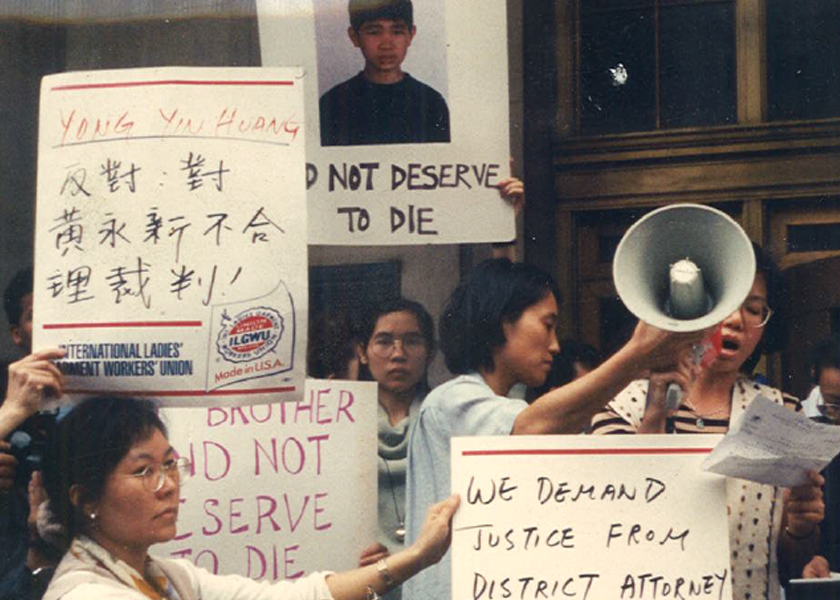

She was central to a multiracial coalition’s effort to successfully push to have a police officer indicted for the March 1995 murder of 16-year-old Yong Xin Huang, who was shot in the back of the head. Five years into this campaign, when the system failed to deliver justice, Lee, in her own recollection, “cried all night in the empty CAAAV office,” resolving never again to harbor “illusions about this system in the United States.”

Born of firsthand experience, Lee developed a ferocity and clarity in her organizing, and honed her analysis and preparation needed for lengthy, complex campaigns. As Wong recalled, by developing political education in CAAAV, Hyun was critical to helping members “connect struggles in different parts of the world to our own work in the United States.”

Lee was skilled at connecting the issues of ordinary Americans to the struggles of people globally. From 2001 to 2007, she was a member of Third World Within, a New York City-based, multiracial group whose campaigns and direct actions sought to link “the struggle between those in the Third World and those who subsist in the Third World within the United States.” The groups sought to expose structural ties between exploitative and racist labor conditions in the U.S, on the one hand, and imperial policies and practices, including war violence, on the other.

Lee participated in numerous international delegations — to Cuba in 1996, to the World Social Forum in India in 2004, to the Philippines on three occasions through BAYAN USA from 2005 to 2015, and to Palestine in 2012. Cuba, the Philippines and Palestine have in common that they were all shaped by militarized U.S. foreign policy. She also perceived lines of continuity with Korea during these trips, and memorably spoke, upon her return from Palestine, about the strange familiarity of being among another partitioned people.

Through her three decades of organizing, Lee’s commitment grew for Korean reunification, and deepened into a priority. Born in 1970, Lee emigrated from Korea to the U.S. in 1981. She was too young to claim membership in the South Korean generation that fought for democracy in the ‘70s and ‘80s, but she keenly felt what she described as “the deep scars” of the U.S.-authored division of Korea and the continued harm of U.S. war politics on the peninsula.

During the post-9/11 era, after George W. Bush declared that North Korea was part of the “axis of evil,” Lee and other diasporic Korean activists researched and raised awareness about past and present U.S. violence in Korea, and made it a focus of their organizing. Disclosing her family’s tragic Cold War secret, namely, that her paternal great-uncles had been killed for daring to oppose Korea’s partition, Lee reflected on how the Korean “people’s desire for reunification” began to take deep root in her, becoming her own desire and shaping her organizing.

Nodutdol, a New York-based, multigenerational, progressive Korean community organization, with which Lee was more recently associated, served as a stepping stone — in keeping with the Korean translation of its name — for her entry into Korea movement work. From 2006 to 2017 she worked as a campaign strategist. Notdutol demonstrated against the Korea-U.S. Free Trade Agreement, against the expansion of a U.S. military base to land in the city of Pyeongtaek, and also in opposition to U.S. deployment of the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) missile system in the tiny village of Seongju. She also worked in support of the South Korean labor movement.

As Nodutdol’s campaigns demonstrated, diasporic Koreans were uniquely positioned within the transnational struggle for a people’s democracy in South Korea, given South Korea’s position as a subordinate to the U.S. Gonji Lee recalls Hyun Lee as being part of a formidable “squad of Nodutdol eonnis (sisters, in Korean), the women who collectively shaped the organization’s focus and direction in durable ways. By extension, their activities profoundly influenced the broader Korean American left. As Minju Bae has remarked, Lee, through the political foundation she helped to build in Nodutdol, “lives on in the organization.”

Prior to Nodutdol’s formation, in 1995, Lee was one of several Korean American organizers in New York who collaborated in the development of the Korea Education and Exposure Program (KEEP), a grassroots political educational initiative that would subsequently be incorporated into Nodutdol and emerge as one of its signature programs. KEEP has enabled Korean Americans and others in the Korean diaspora to travel to South Korea and to engage directly with its progressive and left-leaning organizations, and to visit North Korea on peace missions. Lee took part in the program three times. In 1995, she participated in the inaugural trip to South Korea; she also returned in 2005 as part of KEEP’s 10th anniversary delegation.

Fatefully, in terms of her evolving political consciousness, Lee also traveled as part of the 2011 KEEP (then called “DPRK Education and Exposure Program,” or DEEP) delegation to North Korea. That experience, which fellow delegation member Julayne Lee described as part of a larger “journey for peace and healing,” transformed Hyun Lee’s relationship to Korea.

No longer a space “split in two,” Lee said later that after her trip to North Korea, the country felt like a homeland she could embrace “with my whole heart.” While in North Korea, Lee, who had been taunted in her youth by white American children who told her to “go back to your country,” mused about moving to Pyongyang after reunification. Contemplating the possibility of living in Pyongyang, Lee recalled, “made reunification seem like more of a possibility.”

Lee’s revelations after visiting North Korea also led to a redirection of her talents. Always disciplined as a thinker and strategist, in the last chapter of her life, Lee was a powerful “propagandist,” according to her own blunt self-description, committed to “promoting Korea issues to international audiences, supporting Korean progressive parties, and organizing for the signing of the peace treaty.”

Lee connected with fellow Korean Americans and the general public through multiple media and forums, including radio broadcasts, mainstream and progressive news outlets (including contributing many essays and opinion pieces to Korean Quarterly over the years), policy journals and academic publications, activist presentations, academic talks, and through a blog she created. Through well-researched analysis, Lee sought to shift people’s understanding of Korea, and thereby to transform U.S. policy toward Korea.

One of her earliest policy pieces, a co-authored analysis of Obama’s “strategic patience” policy toward Korea, was the third most influential article the foreign policy analysis website Foreign Policy in Focus in 2013. She was also able to translate her knowledge of U.S. policy toward Korea through her talent as a speaker, offering informed explanations of complex issues in live-commentary format.

From 2010 to 2015, she produced and hosted shows at Asia Pacific Forum, a WBAI radio program. In 2015, along with fellow activist and colleague Juyeon Rhee, she launched the highly influential Zoom in Korea, an English-language blog and news aggregation website that she edited until 2019. From 2016 until her passing, she was an associate with the Korea Policy Institute, a U.S.-based public educational and policy organization with roots in the Korean diasporic peace movement. She used these and other platforms to deliver hard-hitting bulletins from the frontlines of struggles in South Korea, illustrating the harm of U.S. foreign policy to audiences for whom such policy’s effects might otherwise have been out of sight and out of mind.

Lee’s writings from the past decade constitute a significant body of research in their own right. With something akin to gusto, she pored over Korean-language and English-language sources including U.S. government reports, diplomatic statements, studies produced by South Korean progressive organizations, and North Korean materials. Lee’s work with South Korean progressive political parties, including the United Progressive Party, the Minjung Party, and the Progressive Party, gave her a perspective for analysis of political developments in South Korea with hard-hitting critique of U.S. militarism’s effect on the Korean people.

Lee’s writings became a go-to resource for U.S.-based and international readers, including foreign policy specialists, researchers, teachers, community organizers and peace/anti-war activists. Her writings are attuned to the experiences and concerns of ordinary people, grounded in the peace movement, and distinguished by firsthand knowledge of and alignment with people’s struggles in Korea. Her analysis consistently reflects an ethical commitment to how people’s lives come first.

As a driver behind the Solidarity Committee for Democracy and Peace in Korea, which she and others formed at the end of the Myung-bak Lee presidency (2008-2013), Lee wielded her pen as a sword in an unflinching battle against the ruthless and corrupt government of Geun-hye Park (2013-2017). Park is the daughter of U.S.-backed military dictator Chung-hee Park (1961-1979) and a neoconservative ally of Barack Obama.

Seeking to alert the U.S. public to the top-down danger to democracy in South Korea, Lee wrote of the Park administration’s use of the undemocratic National Security Law to dissolve the Unified Progressive Party (UPP) and to jail National Assembly representative and UPP member Seok-ki Lee. Her English-language analysis contained a wealth of damning detail and clarity of critique, and was a unique insight in the Western media at the time. The danger, she made plain, was no less than “a return to the politics of fear that ruled South Korea only a few decades ago when government surveillance and unwarranted arrests of citizens were routine.”

After speaking out against Geun-hye Park’s authoritarianism, whose collaboration was key to Obama’s militarized pivot-to-Asia (also called the Pacific Pivot policy), Lee faced the consequences. In late July 2016, at the beginning of the millions-strong candlelight demonstrations in cities throughout South Korea that eventually led to Park’s ouster, Lee and Nodutol colleague Juyeon Rhee were unceremoniously blocked from entering South Korea. The two were deported after landing at Incheon Airport, and were unable to join the Veterans for Peace delegation they had organized to protest Obama’s imposition of the THAAD system on the people of the village of Seongju.

On their return, Nodutdol mounted a grassroots social media campaign against South Korea’s and U.S. travel bans, seeking to expose the latter as a coordinated inter-country means of repressing international solidarity.

Four years later, in late 2020, Hyun wrote on Twitter about how trans-Pacific agitation by U.S. and South Korean organizations and individuals led to the lifting of the travel ban for Rhee. Lee wrote at the time “She’s now free to return to her homeland.”

Few people were more impactful than Lee in fostering international solidarity over the past decade, and her bilingual skills in Korean and English gave her a special type of cross-cultural effectiveness. Lee promoted international solidarity by using her advanced language skills as early as 2005, while traveling through East Asia with CAAAV’s Chinatown Justice Project. During that trip, she persuaded and enabled the participation of 1,000 Koreans in a grassroots international effort to halt the World Trade Organization meetings in Hong Kong.

As her focus on Korea issues deepened, Lee was one of a handful of diasporic Koreans — in particular, the 1.5-generation of Koreans who came to the U.S. in their youth — who facilitated communication in organizing the transnational Korea peace movement. As Wol-san Liem, international affairs director for the Korean Federation of Public and Social Services and Transportation Workers Union, noted, Lee facilitated “a deeper perspective on the Korean movement to non-Korean-speaking Korean American activists.”

Lee possessed not only flawless command of English and Korean but also a seemingly effortless ability to perform simultaneous interpretation. In 2007, she flew to Omaha, Nebraska, to interpret for Youngdae Ko of Solidarity for Peace and Reunification in Korea (SPARK) who had been invited to speak at a Global Network Against Weapons and Nuclear Power in Space conference. Hyeran Oh, a SPARK member who accompanied Ko, recalls, “Afterwards we heard from so many attendees how beautifully touching his speech was. Such feedback was unusual. We all agreed that it was thanks to Hyun’s translation.”

From that point onward, Lee frequently interpreted for SPARK in consequential settings, including the 2010 and 2015 United Nations Non-Proliferation Treaty Review conferences in New York. Lee also accompanied scholar Gregory Elich, The Nation journalist Tim Shorrock, and civil rights leader Jesse Jackson, Sr., on solidarity tours to South Korea, facilitating their interactions with progressive Korean leaders and organizers.

During their North Korea (KEEP) trip, Julayne Lee recalled that “Hyun would often casually step in to interpret for me in a way that was helpful and never overbearing or condescending. For some of the North Koreans, I was the first overseas adopted Korean they had met and it was an emotional interaction for them. Hyun was there to bridge the communication.”

Lee’s pathway to transnational Korea peace organizing organically converged with her pursuit of healing practices grounded in traditional Asian medicine. From 2005 to 2008, after leaving CAAAV, she studied acupuncture at Tri-State College. Her immersion in acupuncture and herbs was part of a more general pattern of community and labor organizers taking up the healing arts in ways that have enabled and fortified movement work.

In both arenas, health care and social justice organizing, Hyun sought to foster survival in the face of trauma and pain. Indeed, as she conveyed to her herb clinic partner Joo-hyun Kang, she was propelled to go into acupuncture not just because “it was something that she could… make a living at as an Asian in a racist country” but also because she could help fellow organizers and activists “utilize their own individual body resources toward healing.”

Committed to furnishing “accessible and effective acupuncture to people of all class backgrounds,” Lee wrote, on her Woodside Acupuncture practice website, that “acupuncture, like social justice, is fundamentally based on the belief that people have an innate capacity to heal themselves. The needles simply stimulate the body to remember its way back to its natural state, just as a good organizer inspires people to arrive at their own solutions through struggle.”

Recalling Lee’s support of her family, Nodutdol member Minju Bae described “the comfort you offered when my haraboji (grandfather) got COVID at the beginning of the pandemic. It was such a scary time, and my family found so much solace and hope through your herbal medication package and recommendations.” One of her patients, Tiisetso Dladla, described the healing comfort of Lee’s care: “I came to your practice after months and months of chronic pain. You not only took that pain away but healed me enough to allow me to conceive. …I came to you, and you let me rest.”

After she was initially diagnosed with estrogen-positive receptor breast cancer in 2010, Lee had a mastectomy and her cancer went into remission. By mid-2015, plagued by a worrying chronic cough but unable to get her primary doctor to authorize a scan to ascertain if her cancer had returned, Hyun employed a strategy she had learned as an urban community organizer: She checked herself into the emergency room to trigger the treatment she knew she needed.

At that point, she learned she had advanced inflammatory breast cancer, a rare and aggressive form. Her oncologist advised her to prepare to die. Never one to give up without a fight, Hyun researched cutting-edge treatments and remained buoyant in conversations about her health with friends. Through a combination of allopathic measures and traditional Asian medicine, including ginseng from North Korea, she prolonged her own life far past her oncologist’s predictions. Those around Lee cheered her on, knowing every extra moment was a victory. Quietly, however, beginning in 2015, she began Buddhist meditative practices, envisioning her own death and the decomposition of her body.

Following Lee’s diagnosis, knowing she seldom traveled for leisure, Juyeon Rhee and I organized a road trip to Joshua Tree National Park for the early summer of 2016. Lee asked to go on mid-day hikes, even though the sun was baking the earth around us; she somehow remained cool as a cucumber, never breaking a sweat. “I could live here in a trailer,” she mused aloud, “This is heaven.”

During this trip, the three of us had conversations about organizing, shared stories, cobbled meals together, marveled at the stars in the desert sky, and alternately laughed and cried. We also butted heads. No nonsense in all things, Lee prided herself, much to the admiration and frustration of those around her, possessing no nunchi (the social sixth sense prized in Korean society). She viewed it, she said, as a socially-ingrained, gendered sensibility essential to the reproduction of Korean heteropatriarchy. “Oh my god, that’s your philosophy? That explains so much!” Rhee exclaimed when Lee shared her views.

Unfussy and modest in her demeanor, Hyun had a penchant for simple pleasures. At the same time, she voraciously consumed the worst possible TV and had notoriously cheap taste in food. Yul-san Liem, operations director for the Justice Committee in New York and a former Nodutdol member, recalled Hyun’s inexplicable devotion to the show, America’s Next Top Model. Her ex-girlfriend Kisuk Yom remembered how “she used to eat cheap street food with a special photogenic smile on her happy face.”

Eunhy Kim, a fellow founder of KEEP, also recalled that during dwipuri (an after-party following an event) “unlike many of us who always sang the same old sappy songs at the noraebang [Korean karaoke-style business], Hyun somehow always knew the upbeat recent Korean songs.”

Nodutdol members recall Hyun’s dismay in 2013 during a Los Angeles trip,when a bold seagull swooped down, plucking an uneaten veggie burger out of her hands at Venice Beach. It was a story she would retell with palpable pathos. Hyun also insisted on using a whole budget-sized bag of garish henna she had purchased in Chinatown to dye her hair, despite friends pleading with her to throw the rest away.

In the last few years of her life, Hyun worked with the women’s peace initiative for Korean peace and reunification Women Cross DMZ, putting her organizing skills and policy acumen into powerful motion. She launched 12 regional chapters of Korea Peace Now!, a global offshoot of the organization, and advocated inside the Washington DC Beltway for support of a peace treaty to end the Korean War. From 2019 to 2020, she labored to promote a legislative initiative (House Resolution 152), supported by 52 representatives, that called for a formal end to the Korean War.

In mid-January of this year, speaking over Zoom about the urgent need to end over seven decades of war on the Korean peninsula, Lee looked and sounded unwell, but sought to reassure her audience: “You might notice that I cough a lot tonight. Don’t be alarmed. It’s just a little condition I have. …Hopefully it won’t be too distracting.”

Politically active until nearly the very end, Lee continued doing public education around the unresolved Korean War. As Sally Jones of the New Jersey and New York chapter of Korea Peace Now! recalled of one of Hyun’s final presentations: “Most of the people…had no idea Hyun was ill. Before she began, she told people she might cough a little… but that everything was perfectly okay. …And then she proceeded to give a brilliant presentation and answered every question with such grace, patience, and deep, deep understanding.”

Near the end of her life, Lee’s friends, D. Chou and Mijeonga Chang, lovingly served as her primary caregivers. Hyun is survived by her parents, Jae-on and Young-ja Lee, her sister Tina Lee Hadari, and nieces Tali and Emma. Before her death, she requested that any commemorative donations be directed to the Tongil Peace Foundation, which she and other Korean diasporic activists created more than two years ago with their own money. The foundation is intended to foster Korea peace and reunification work for future generations of organizers.

Roughly two months before her passing, Hyun posted a heartfelt online tribute to her comrade Jeong-yong Yang, Secretary General of Korean Americans for the Progressive Party of Korea. Like her, Yang had battled cancer for many years. “Dongji,” she wrote in a luminous message that we might now fittingly direct to her, “thank you for your radiance and humility while here on earth. We who remain have much to do to fulfill your dream of peace, democracy and reunification. Go freely now. Hope you soar as high as you desire and watch over us as we redouble our efforts.”