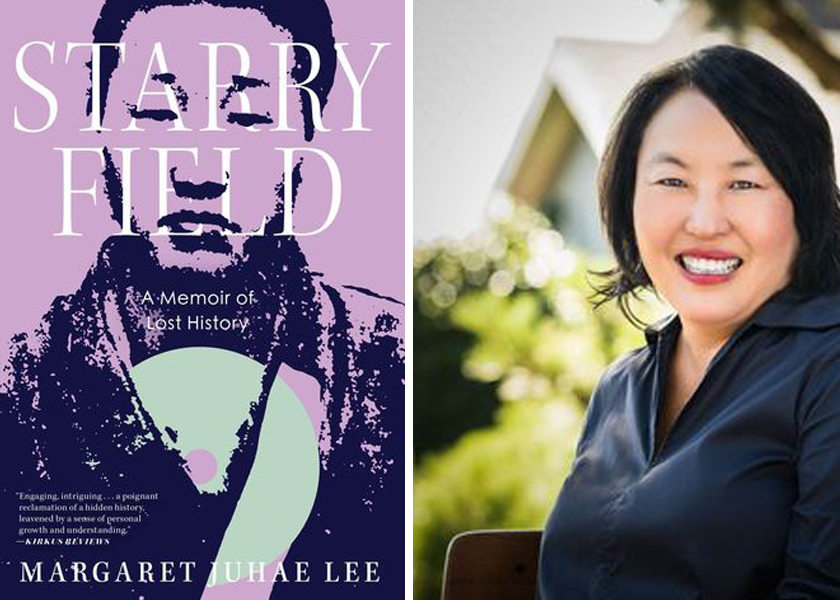

Starry Field: A Memoir of a Lost History ~ By Margaret Juhae Lee

(Melville House, Hoboken, 2024, ISBN #978-1-6858-9093-3)

Review by Bill Drucker (Winter 2025)

This is a poignant narrative of author Margaret Juhae Lee’s grandfather, Chul Ha Lee. Within his own family, he was labeled a rebel, a traitor and a family black sheep. Because his granddaughter wanted the truth of his legacy, she did meticulous research that revealed that his criminal conviction and incarceration were for acts of patriotism in the cause of Korean independence.

Lee’s memoir is part personal investigation of family legacy and identity, which bridges three generations and two countries, and part Korean social history.

The author deploys investigative journalism to authentically report the story, including interviewing her grandmother and researching archival files to assemble an account of her grandfather’s remarkable life. Chul Ha was a student revolutionary who was arrested and imprisoned in 1929 for protesting the Imperial Japanese colonization of Korea. At the time of his death in 1936, he was virtually forgotten about because of his criminal reputation and because of the many years of turmoil which include two wars, Korea’s liberation, and its rebuilding. His name would be reclaimed and honored as a Korean patriot 60 years later.

The focus of the memoir is gleaned from three long interviews Margaret did with her grandmother. To write a true portrayal, Margaret had to develop trust with her sources. To reinstate Chul Ha’s name in the family with honor, she had to banish her shame and secrecy and apply her journalistic scrutiny to dig deep into the family history.

The author was born in the U.S., and grew up in Houston, Texas. Her parents were both born in Korea, are bilingual in English and Korean, and have family ties in Seoul. When Margaret approached her grandmother (halmoni) to ask more about her grandfather’s life, her grandmother asked her why she wanted to know such painful things. Margaret replied that she sought the information to understand what happened in the past, to understand family history, and to better understand herself.

The grandmother is reticent at first, and even Margaret’s father, Eun Sul who translated for his daughter, was hesitant. Margaret is surprised that there was such a sense of family shame that they preferred to suppress any talk of her grandfather’s history rather than discuss it.

When his daughter began the memoir project, Eun Sul also had little knowledge about his father. His mother, fearing the Japanese, had burned all of Chul Ha’s books and writings after his death, rationalizing that her silence would protect Eun Sul and the rest of the family.

Margaret thought of her life as fragmented. She had lived and been educated as an American. She lost much of her Korean fluency and chafed at her parents’ Korean traditions. In her consciousness, memories of Korean holidays and observances were mixed in with a Sears Christmas tree and images of her dad in a La-Z-Boy. She remembered family trips to Korea as boring. For her own survival, after graduating from high school, Margaret applied to and was accepted at a college in New York.

The mission to write about Chul Ha originated with her father. He took a two-year sabbatical to do the research, but then got tuberculosis, which led to surgery and a long convalescence afterwards.

To fill his days, and to give herself a mission, Margaret re-boots the family research and asks her father to write anything and everything about Chul Ha, from the recollections of Halmoni and Eun Sul’s brother, with information from other uncles and Chul Ha’s schoolmates and friends. Margaret told her father that her contribution would be to go to Korea to search for records.

Chul Ha was born in 1909 in a remote village outside of Gongju. A year after his birth, the Japanese annexed Korea. He was home-schooled until 1921. The family moved closer to the city and Chul Ha began his formal education there.

In 1924, at age 15, he married Kum Soon Min in Chongju. His defiant patriotism started early. Even in high school, Chul Ha organized anti-Japanese protests. He was beaten by the school principal (a Japanese man). He and his younger brother would scribble graffiti like “Japanese Go Home” and “Long Live Korea.” The police never caught the graffiti rebels.

After high school, he became active in the anti-Japanese movement. Suspecting his activities, Japanese police surveilled him.

In 1999, Margaret initiated her second of three major interviews with her Halmoni, this time in Seoul. The grandmother was still reticent, but Margaret’s mother took Margaret’s side, imploring her, “Do it for your granddaughter.”

Chul Ha was arrested and sentenced for his anti-Japanese activities in 1929. He was incarcerated in the notoriously harsh Seodaemun prison in Seoul, where visitation was once every two months. Chul Ha was there for more than four years. He never talked about prison life, even after his release. After getting out of prison, he traveled to Gongju to see family and friends. Sadly, he contracted both pleurisy and diphtheria, never recovered his health, and died at age 29.

In fact-finding trips to Korea, Margaret met her grandfather’s old friend, Dr. Shin. Translator Jungmin assisted Margaret in her interviews with Shin and three other elders, including Dr. Lew, Professor Chi, and Professor Yun. She writes that her patience was stretched thin, as she endured their ramblings and condescending remarks.

Her search also led her to police and prison interrogation records, and to a publisher, Mr. Kim. Kim had obtained records that he said contained information about her grandfather. He bargained with Margaret for payment for them, and did not allow her to view any of the records in advance. Despite some indignation, Margaret eventually pays up the equivalent of $600.

The records are not a disappointment. They consist of police and prison records, and include accounts of interrogations and other information. They are in Chinese and Japanese; many are written in a messy scrawl. The records show that Chul Ha spoke to his interrogators intelligently and without fear. Margaret’s mother helps with the Japanese translations.

The third interview Margaret does with her Halmoni is more revealing of grandmother Kum Soon Min than of her activist husband. Min tells Margaret that Chul Ha confessed to her that he never wanted to marry. After his early death, Kum Soon is left to carry on for almost 70 years alone. She worked and raised her family through some of the most turbulent times in modern Korean history. She had a job at an orphanage, and was a deaconess at her church in Seoul.

Margaret skillfully transfers her sense of focus and energy for her quest to the page. She writes of her investigation in detail, describing how she followed clues like a detective. She conducted interviews with close family members as well as strangers. The interviews brought her to new sources, people, and places in South Korea. She also describes her frustration with the bureaucratic roadblocks and resistance of family and friends.

The author also describes how she struggles because of language and culture barriers. Some Korean authorities are hesitant to give her any help, or are just scornful and resistant because a Korean American woman is asking for such specific information. Many officials refuse to help her unless they get paid for it. She also pays off friends of the family in exchange for their information.

After exhaustive searching, the results she turns up are significant. They are sufficient to restore her family’s missing history and exonerate her grandfather’s name. In 2000, Margaret obtained all her grandfather’s official police and interrogation records. Seven bound volumes were recovered, remarkably intact even after so long. The records renewed her interest in finishing the memoir and the story of her grandfather’s short but important life.

After showing the records to her father, Margaret resumed her organization and writing of the memoir. Remarkably, Chul Ha, a prisoner and survivor of the infamous Seodaemun Prison, would buried twice. Upon his death in 1936, his body was interred at a mountain site that his father had reserved for himself. In 1995, after he was officially designated a Patriot of Korea, his remains were transferred to a site at the Taejon National Cemetery, where Margaret’s grandmother is also buried.

In 2007, Margaret, with her husband and son, visited the Taejon National Cemetery and placed flowers on the graves of her grandfather and grandmother. Her diligent research uncovered the hidden truths of her grandfather, Chul Ha. The records, some secured from one opportunistic publisher and the rest eventually obtained from police, exonerate a forgotten Korean political activist, and served as closure for the Lee family about their brave and colorful ancestor.

This memoir is a deeply-felt narrative of a Korean family’s legacy in the context of Korea’s turbulent past. The family photos of three generations add to this saga. The title of this memoir comes from Chul Ha’s tomb marker, inscribed with the name Sung Ya or Starry Field.