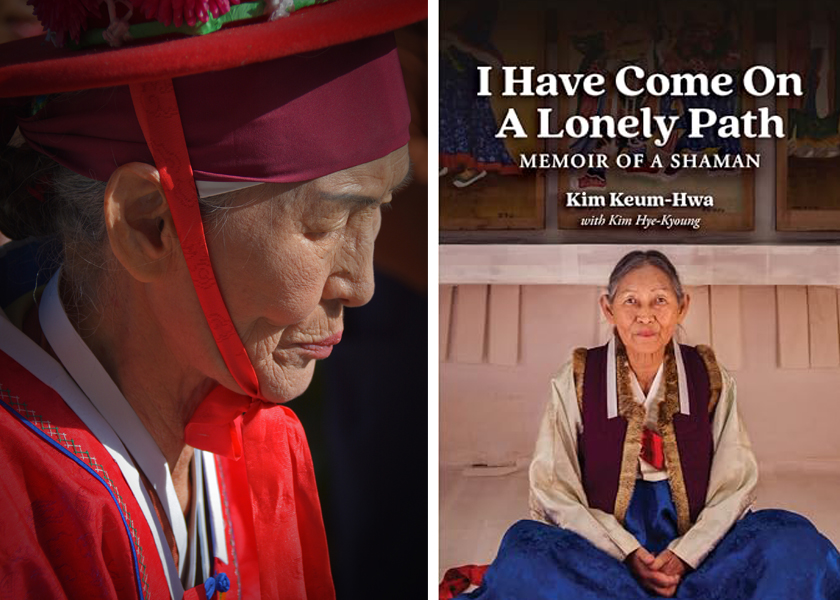

I Have Come on a Lonely Path: Memoir of a Shaman ~ By Keum-Hwa Kim

(Alpha Sisters Publishing, Alpharetta (Georgia), 2024, ISBN #979-8-9869-3732-8)

Review by Bill Drucker (Winter 2025)

The somber title of this memoir refers to the shaman’s role to be apart from the community, a person who is both revered and oppressed, due to a special connection with the spiritual.

This story describes the shaman’s destiny as a combination of blessing and curse; it is a lonely life of following a talent and skill that is both sought after and also persecuted. The tale is at certain points a harsh one; Keum-Hwa Kim was touched by physical abuse, suicide, poverty, colonial brutality, war, and political developments including her country’s liberation from occupation and its trials through many different governments. Her life also parallels the history of modern Korea.

The Korean tradition of being a shaman (in Korean, mudang or sometimes manshin) has a long legacy in Northeastern Asia, in an area that includes Siberia, Mongolia, and Manchuria as well as Korea. In Japan, the Ainu culture has its version of shamanism. In the indigenous shamanism of Northeast Asia, tradition attributes spiritual qualities and even personalities to many animate and inanimate objects, including mountains and other geographical features, as well as trees and other plants and creatures. Spirits of the dead inhabit the spirit realm and can reappear in the earthly realm.

The spiritual gifts and work of the shaman are similar across these cultures, and include various public and private actions that help them communicate with and persuade spirits to do actions to benefit earthly beings, or to cease activities that harm them.

The memoir, by perhaps the most famous mudang in modern history, is a personal reflection that was first published in Korean in 2007. At the time of her writing, Kim was at the height of her career; she was conferred the distinction of holding an “intangible cultural asset” of Korea. She established a training center, called Keumhwa-dang, to pass on her knowledge of certain rituals to her successors. She also founded an organization dedicated to the exchange of information with other cultures about indigenous shamanic practices.

During her long career, Kim appeared at countless Korean festivals and commemorations and visited the U.S. many times to teach and offer rituals. Director Chan-kyung Park’s film Manshin was inspired by the shaman’s memoirs. (The English film title is Ten Thousand Spirits, which is the literal meaning of the Korean word manshin.) Kim died in 2019 at age 88.

The publisher’s prologue describes how the original Korean language memoir was not available to be reprinted after the publisher went out of business. Publisher Seo Choi explains on her website that the project required guidance from the spirits. She wanted to produce the memoir in English, and appealed for financial assistance via a crowdfunding site. She also received a small grant from the Literature Translation Institute of Korea. Her Alpha Sisters imprint includes a few other books related to shamanism, rituals, and other topics on Korean traditional culture.

Kim’s 2007 story is the heart of the English language version of this 2024 memoir, entitled I Have Come on a Lonely Path. Publisher Choi is a (Korean American) mudang, and the work is translated by Peace Pyunghwa Lee. Both Choi and Lee write their own prologue to the memoir.

The story is divided into five sections in which the mudang reflects on her beginnings in poverty, and how her life’s work has been a calling, a blessing and also a burden. She describes her joy in helping people to be healed physically and psychologically, and her own surprise when her work has often healed her subjects, sometimes even when she was rejected by the person she prayed for and intervened for.

She frequently discusses how Korean indigenous religion has been viewed and misunderstood and oppressed by every government in Korea since the Japanese rule of 1910-1945, and is still reviled by Korean Christian groups today. Her writings reveal regional history, village and community life, and lesser-known facts about North Korean traditions, culture and dialect.

Kim was born in 1931 in a village in Hwanghwae province. She was initiated as a shaman at age 17 by her maternal grandmother Cheon-il Kim — she refers to her as her “spirit mother”– who became her guide to the manshin’s path.

She describes how, as a child, she experienced being filled with a kind of energy that caused her to tingle all over and be filled with boundless physical energy and stamina; she would dance with the feeling that her feet were barely touching the ground. As a child, that energy drove her to antics and spirit-filled pronouncements to other children that would scare them away. It was many years before she understood and could control the link she held between humans and spirits.

Kim was treated as an unwelcome second daughter, particularly by her father. In his worst moments, her father grumbled that Kim should have been killed at birth. Forced into an unhappy marriage at age 14, Kim lived with her insensitive husband’s family. Her mother-in-law mistreated and physically abused her. Kim ran back to her family a number of times until the marriage was dissolved.

Kim affectionately calls her mother Ommai (oh-mah-ee, the North Korean dialect for the word omma or mom), and her mother was a rare source of support for her. Kim describes how women’s lives were marked by long days of physically-demanding chores. During her childhood, most of the people’s crops were confiscated by the Japanese occupiers, leaving farmers with a very meager living.

Kim and other young women labored in the rice paddies, and she describes the miserable work and how she pulled leeches from her feet and legs. She mentions how the village people showed solidarity after an epidemic sickened some families. A specific house would be quarantined, but not shunned. A quarantined family would place jugs by their door, and the neighbors would fill them every day.

Knowing that Kim was a young shaman, some families would tell their children not to be friends with her. This rejection added to her loneliness. Kim’s training was harsh. As her main teacher, Kim’s grandmother sometimes used verbal and physical abuse to punish her. Kim was made to memorize many invocations and prayers, and learned how to care for the ritual clothing and instruments. Eventually, Kim began to perform her own guts or rituals. Some were awkward, and others were traumatic, but Kim was on the spiritual path.

After 1945, when the Japanese occupation was over, there was a struggle between Communist powers in the north, and the U.S. in the south, which plunged the country into civil war. During this time, her family migrated south to Seoul.

Kim describes waves of shaman persecution during her career. Communism also had little tolerance for religious practices in the North. In the South, under so-called democratization, the government pushed shamanism out of the mainstream. The indigenous religion of the Korean people was officially reviled as superstitious and irrelevant.

Kim’s family survived, and during times of persecution, Kim continued to practice surreptitiously. She supported her family with her work as a shaman. She unexpectedly married for a second time, but her new husband was useless; he took the money she earned and spent it on himself. In a last act of decency, he declared that he was no good and proposed they should divorce. Kim was 25 when they met, and after 11 years of a second unhappy marriage, she was single again, and middle-aged.

As Kim tells it, her calling to the manshin way of life was her salvation. After the regime of dictator Chung-hee Park was over (in 1979), people were no longer fearful of association with shamanism, and interest in the practice grew. Kim was invited to participate as a shaman in many public celebrations and festivals. She was also asked to go to the U.S. and, at one point, stayed for three years to perform and educate about shamanism.

After her return from the U.S., Kim established her shrine. She continued to perform guts, and to teach, lecture and take other steps to preserve the shaman traditions.

This memoir reads like a collection of engaging tales, going back and forth in time with the shaman’s musings about how she views her life, discussion of her beliefs, childhood experiences, adult accomplishments, and many other memories and reflections. There are interesting biographical and historical notes about the turbulent times she lived through. There are also many gems of information, including North Korean words and phrases.

The significance of this memoir cannot be understated. There have been studies of shamanism, and films of actual shaman rituals, but firsthand autobiographical narratives by shamans are rare. Kim wrote her story with help from her grand-niece, who is also a shaman. The memoir is enhanced by many photos, from early black-and-white posed family photos of Kim with her mother and grandmother, to more recent vibrant images of the powerful shaman in full regalia engaging in colorful rituals.

Kim does a good job of reflecting on her beginnings as a lonely girl from North Korea who, with faith and patience, followed a spiritual path to become Korea’s most famous and most sought-after shaman. Apart from teaching the reader about the spiritual quest of shamanism, this memoir is worth a read because of the perspective of a very unusual and determined person who lived through some turbulent times in Korea’s modern history.