The lead-up, the loss and the legacy of the Itaewon Halloween tragedy | By Tom McCarthy (Fall 2022)

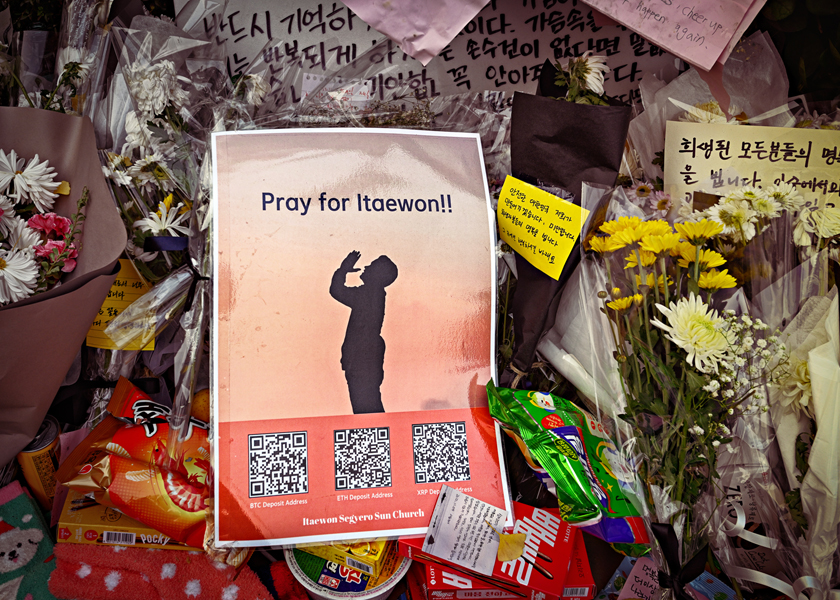

The scenes from Itaewon’s Friday night Halloween festivities and the disaster that followed have been splashed across front pages and screens around the world, the tragedy rocketing to the top story position on CNN, the BBC, and Le Monde.

As of Tuesday evening, November 2, 156 were dead and 151 injured.

Twenty-six foreigners and six underage students were among the dead, and there was an almost two-to-one ratio of women to men who were fatally injured.

The details have been rehashed ad nauseum: roughly 130,000 people, according to South Korea’s interior minister, most of whom were in their 30s or younger, descended on the “foreigner district” for likely the second biggest annual party night in Seoul after New Year’s. On Saturday, the neighborhood was patrolled by 137 police, a ratio of one officer for every 100 partygoers.

Halloween in Itaewon got global awareness with the success of the 2020 K-drama Itaewon Class; in the second episode, the characters are shown reveling in the festivities. In a genre known for injecting artificial drama and exaggerated plot points, the most unrealistic aspect of that series may have been the depiction of Halloween in Itaewon, with cameras chasing the characters as they caromed through the streets like balls in a pinball machine.

For the past six years, I have made a pass through Itaewon on Halloween weekend, and it has never looked like that.

The density of the crowds has always resembled, to a lesser degree, the harrowing footage recently projected around the world by international news agencies. I always felt a sense of imminent danger in that neighborhood on Halloween weekend, though it seems that not everyone considers it such a risk.

The one aspect the drama captured accurately was the liveliness of the evening. Costumes range from cute and sexy to funny and authentic, with some verging on Hollywood-quality design, with animatronic parts, sensor-activated lights and sound effects. The outfits are definitely worth seeing against the backdrop of pulsing neon, glimmering signage and ear-shattering electronica. It is an experience unlike any other, and that is what draws throngs of people from around Seoul, the country, and beyond.

On Friday night at around 8:30, the night before the disaster, I joined some friends to soak in that festive atmosphere once again. It was the first all-out celebration since the pandemic-related restrictions toned down all celebrations during the last two years.

With each passing bar packed to capacity, we retreated down a narrow alley linking the main alley and the main street, and stopped into a familiar bar to enjoy the easy access to quick service and sights of the main street from the comfort of padded seats. Though undeniably less crowded than the main alley behind us, the views of the avenue offered a taste of what was to come the next day.

This district was once known as a sort of frat row for U.S. soldiers from the nearby garrison before slowly evolving into a cosmopolitan food and club area. It is laid out like a ladder. The main four-lane avenue running almost perfectly from east to west is paralleled to the north by a narrower street, essentially a wide alley, lined with countless bars and clubs. “Rungs” of narrow alleys ranging roughly from 10 to 25 feet wide link the two east-west routes on what the news has described as a “hill” but would more aptly be described as an incline from the main street to the main alley.

We stayed at the bar watching increasing numbers of costumed partiers pour into the alleys transporting entrants to the alternate reality above until around 11 p.m. before we headed out. Hanging a left, we walked up the incline and turned right onto the main bar alley and work our way east, toward the site of what would be the fateful intersection.

I was unfortunate enough to find myself behind a friend who, though I love him like a brother, drives me to the brink of insanity with his unique talent of always preventing any form of silence, welcome or awkward. As we inched slowly down the road, he couldn’t help but frequently come to a full stop so he could turn around and make an observation.

Every time he did so, I could feel the compression build up rapidly against my back as columns of people log-jammed behind me. I felt the stress building up inside me as I barked at him to shut the hell up and keep going. We were about a quarter of the way down the main alley when my friend decided to turn off and head out to meet his girlfriend, jostling his way through the same side alley directly (to the west of the Hamilton Hotel) that would make international news a mere 24 hours later. I continued on behind the rest of our group, thinking to myself, “I’m too old for this shit,” as I watched him work his way down the small passageway not yet littered with festive rubbish or packed with helpless souls.

It has been revealed, through emergency service call transcripts, that as early as 6:34 p.m. Saturday, some four hours before the full-on emergency, police received the first report that the situation had the makings of a terrible accident. Calls kept trickling in, a total of 11 in the four hours before the emergency was declared. After the first four calls, the dispatchers replied that officers were already on the scene, and took no further action.

It was at around 10:22 p.m., after the situation had spun out of control, that emergency services swung into action. Bodies began piling up at the end of the small, now infamous “ladder-rung” alley adjacent to the Hamilton, and the initial first responders began trying to first pull victims out from the bottom of a pile. One responder described as a pile “seven, eight – no, 10 – rows of faces” high. Witnesses reported that those at the top of the incline fell first, which created a cascade of falling people, who became the heap of bodies at the end of the alley along the main street.

Within an hour, bodies were being laid out along the main sidewalk, and then on the adjacent street, where police, paramedics and firefighters were joined by Mario, Ronald McDonald and the Joker in performing CPR. Seemingly unaware of the gravity of the emergency, perhaps assuming it was a medical emergency for paramedics to take care of, or bar fight to be handled by the police, passers-by continued to party and watering holes continued to pour drinks.

Emergency responders began to remove injured victims as quickly as they could, sending them to and any hospital that had space. The victims left behind possessions such as ID cards or cell phones as well as shell-shocked friends who were not informed where the victim was being sent. This led to mass confusion for families trying to find their loved ones, a problem exacerbated by time and distance for the parents of foreign victims.

Families flocked to Seoul or sat by their phones thousands of miles away, waiting for a glimmer of hope. For the families and friends of the 151 or more people killed on Sunday, that hope never came. So many lives were lost, not to a terrorist attack or a structural failure, but to something more mundane – a crowd.

Whether chalked up to inadequacy, ineptitude or arrogance, how are these families supposed to make sense of this loss? How can the 35 million won offered by the government (about $24,500, a substantial sum in cases like this by Korean standards) possibly come close to compensating for a lifetime of experiences taken cruelly from not only the victim, but their families and friends?

What has made this disaster all the more distressing is the excruciatingly slow devolution of the entire situation. Calls came in for hours preceding the tragedy, but the police dispatch apparently did virtually nothing in response. Within hours, Interior Minister Sang-min Lee came under fire from his own conservative party for claiming that the size of the expected crowd was not statistically large enough to merit a stronger police presence. Indeed the 137 police initially on patrol were a substantial increase over the 37 to 90 officers dispatched during similar festivities before the pandemic, all of which went off without a hitch.

This is not to exonerate preparations on the minister’s watch in any way, although evidence now indicates that there was absolutely a systematic breakdown. However, a devil’s advocate may argue that without eyes on the ground, dispatch likely assumed the weekend was unfolding like every other Halloween. The police on site may have felt that their numbers were adequate, and surely had no expectations that a disaster of this magnitude could possibly unfold. Initial evidence indicates they were unaware of the incoming distress calls fielded by dispatch in the hours before the incident, they were able to react only after it was too late for too many.

There was little to be done anyway, with no police presence to be seen along the main alley, according to witnesses. It would at first have seemed unnecessary with the aimless and multidirectional crowd resembling the most densely packed game of Asteroids imaginable. However, compared with past similar festivities, these crowds were not at any greater risk than at any past events of this size. Strings of friends shifted at a crawl through the throngs of equally slow clusters of people, moving with only a general sense of direction, carried along by the ebb and flow of the crowd like leaves in the ocean.

It seems that the crowd grew and became more compact as the masses converged on the three-way intersection on the Hamilton Hotel’s northwest corner, a crossroads that offers the most efficient access to the most popular bars on the street. The compaction was gradual to the point of imperceptibility, leaving those in the middle of it with few options. Videos show one guy scaling a storefront to perch on a sign, a move many apparently thought was just Halloween shenanigans; there were phone videos of the climbing man who had clearly grasped the peril at hand.

Finally, the streets hit their breaking point. Some witnesses have claimed they heard young men at the top of the incline yelling “push!” The allegations are unsubstantiated as of now – if they are found to be true then the perpetrators should be subject to the full force of the law – but the descriptions by witnesses make it sound like there was no malicious intent, just tragically mistaken, and regrettably, alcohol-induced enthusiasm, and a shocking disregard for crowd safety that is all too common in a metropolis of 25 million people.

And therein lies the existential devastation of this accident, beyond the juxtaposition of people in fun costumes begging for help beneath a heap of unconscious bodies. The police received ample warning that the situation was devolving into a tragedy of terrifying proportions, but the system suffered a catastrophic failure. The police dispatch seemingly failed to impart the urgency of the situation to on-call responders. If forewarned, officers on site could have called for backup to re-route people to safer and less crowded routes.

In hindsight, all the risk factors were there for a crowd-compression disaster. But it is easy to understand, especially having been there the night before, how so many chose to ignore the signs. There was probably nothing out of the norm for a Halloween night. People were swept along with the crowds and the fun until they were in a crush that was too deep to escape.

We typically think of crush incidents as taking place in stadiums of rival fans, where the accident is preceded by scenes of angry football hooligans spewing vitriol against families supporting the other team. We imagine concert venues at which counterculture anarchists are in a fury of headbanging to raging nu-metal; or at political protests, where angry demonstrators are responding to rhetoric intended to incite aggression. There is a certain ratcheting up of tension in these scenarios that can lead to a sudden crowd panic leading to crush accidents. While no less tragic than what happened in Itaewon, that such a dangerous combination of huge crowds, small spaces and big emotions can cause such incidents is almost unsurprising.

But concerning Saturday’s tragedy in Seoul, no evidence of a specific flashpoint has emerged thus far. Emergency call logs show that some people were acutely aware of the risk and did the right thing by calling police and urging them to intervene, and there was a failure to respond properly at some or even all levels. It was eventually, not suddenly, that there were simply too many people in too small a space, and too many calls for help, drowned out by the cacophony of throbbing pop hits blaring from the bars and clubs encircling the tiny alley.

The emergency response system failed, not only the victims, but also the police first on the scene, with one video showing the desperate face of one officer attempting futilely to redirect the crowd, a lone figure whose pleas for compliance and assistance were swallowed by the din of the party surrounding him. A separate video, captured hours later, shows one lone officer, suspected to be that same person, slumped on the sidewalk, weeping over the incomprehensible sadness that cut short a night that was supposed to be a celebration, and cut short more than 150 lives.

The government moved swiftly, as it always does regardless of political party, to respond appropriately, or at least look like it. The police chief of Yongsan District, which includes Itaewon, was fired on Wednesday evening. A special investigation team raided eight emergency service and government offices and headquarters. The ministerial press releases about financial recompense came across my news desk several times on Tuesday and Wednesday. Pledges to reform emergency response and crowd control guideline emanated from every governmental ministry and agency that might tangentially be culpable.

I certainly hope that something can come of this, some substantive change that doesn’t completely sterilize what makes Korea Korea, but does make it a safer version. As much as I would love to see a blitz of firings and a flurry of wrongful death suits, a part of me believes that, despite the warnings, no one genuinely fathomed it could happen here; not in the home of the beloved BTS Kpop stars and Oscar-winning director Joon-ho Bong, the land of world-class public transit and world-beating internet speeds. Nobody imagined it could happen until it was too late.

I suppose the point I’m belaboring is that while the videos are alarming enough to induce vicarious trauma, the start of that evening was not much different from the usual Halloween weekend. Perhaps the crowds were denser, but it was still calm and festive. How could this lead to such a terrible tragedy? But over the course of Saturday night, one of South Korea’s biggest peace-time disasters transpired after snowballing from conditions not much different than the crowd I had experienced the night before.

My Friday excursion came to a stifling and exhausting end as I finally made my way through to the end of the street after a claustrophobic 45 minutes of working my way out of the neighborhood into a wider, less crowded area. Fed up with the whole ordeal, I declared my intention to go home and veered off on my own.

As I walked along the sidewalk on the main road, which was busy but not as suffocating as it would be the following night, I thought about how I used to enjoy Halloweens in Itaewon; the sights, the sounds, the costumes and the crowds. And about how, now age 32, I finally feel like I have grown too old for this shit, having subconsciously begun avoiding the crowded, overly-enthusiastic street parties in exchange for the quiet safety of a sparsely-populated bar that lets me put on Bruce Springsteen, an option that grows more and more appealing to me as I get older in Seoul.

And that is the real tragedy of Saturday; of the 156 victims so far, 116 were in their 20s or even younger and some 90 percent were younger than 40. They won’t get to sit around with friends and reminisce about the bad decisions they made for the sake of a wacky experience, or laugh about what they considered fun when they were younger.

They will never have the chance to learn the lesson I learned and that most of us as the years pass, that they should have been able to carry with them into old age. They should be able to think back and fret about their children on the weekends the way their parents worried about them on Saturday.

Instead, the nation, and maybe the world, is learning that lesson on their behalf.

All we can do, then, is whatever we can do to ensure that other young people have the chance to grow old. We need to take this experience to heart as we pick up the pieces of our broken ones and strive for a better tomorrow.