Unrest and protest after the senseless loss of young lives will not be short-lived | By Tom Coyner (Fall 2022)

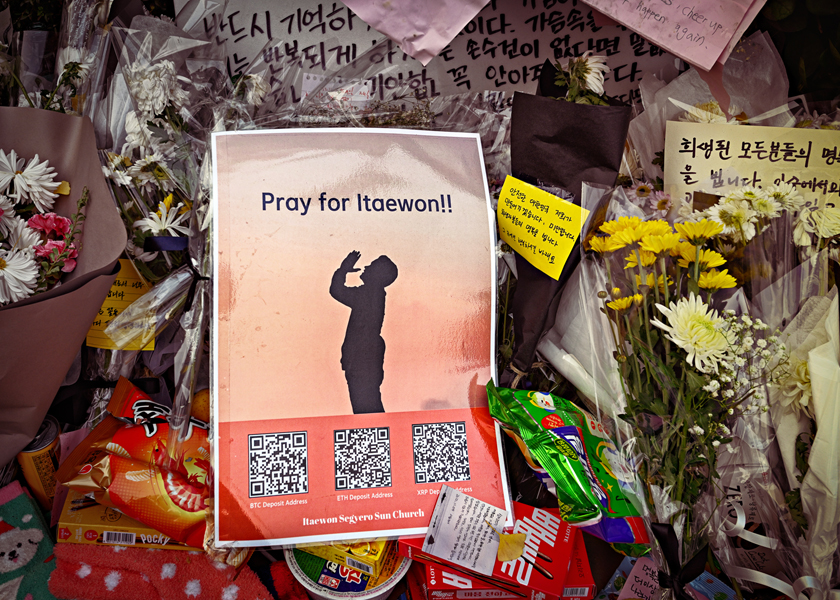

Late in the afternoon of Wednesday, November 9, Yeong-do Jeong and the Gyeonggi-do #61 Intangible Cultural Heritage Association, consisting of about a dozen dancers and musicians, assembled in front of the Hamilton Hotel in Itaewon. Leading up to the hotel, on the subway exit walls, and seemingly on every available surface, there were post-its and other notices in various languages wishing peaceful repose for the dead and sympathy for the surviving family members whose loved ones died in a horrific crowd-crush accident on Halloween night.

Around the hotel, flowers in varying degrees of wilt and freshness laid in row after row on multiple piles. A bearded Buddhist priest determinedly banged his moktak block while standing in his socks on a cushion. However, for two hours, this shamanic organization took center stage, next to the notorious alley leading up the hill. Their purpose was to perform a regional ceremony of Gyeonggi-do known as a jari-geoji (the names vary by region), a ritual of purification and liberation of the spirits of the dead.

The intent of such ceremonies is two-fold. The rite is meant to purify the spirits and to give them release to heaven so that they do not malinger and become confused and angry on earth. The ceremony takes place at the place of death and pries the spirit away from that location so it can move on. Ceremony participants pick up rice paper sheaths from the floor or ground at the location of death to symbolically rip souls away from their attachment to earth.

The ceremony also provides relief to the deceased’s survivors, so their lives will not be troubled by their dead relatives who are conflicted between leaving their lives on earth and realizing their destiny in heaven. The process seems complicated and involves 12 stages over a two-hour period. During that time, contact is established with the spirits, and those spirits are channeled into trained volunteers.

Passers-by observed a banging of symbols and drums, dancing, women dressed in traditional funeral attire going into trances, moaning and wailing as they channeled various spirits. They repeated exclamations from, or on behalf of, the dead such as “What happened?” and “Let me live!” Some of the women channelers were shaken by physical and psychological trauma they experienced, and needed assistance to recover.

This spiritual tumult of the ceremony is a microcosmic version of what is playing out in South Korea as a major national tragedy. I was brought back to the days following the Sewol Ferry sinking of April 2014, in which 250 high school students and their 11 teachers from the city of Ansan, traveling together on a class trip, died after their ferry capsized in heavy seas. It was found that the victims’ deaths were due to poor emergency procedures and cost-cutting measures that made the ferries less safe.

After that tragedy, there was a long period of blaming the government for its part in creating the conditions in which such a momentous loss of life could happen during a routine ferry crossing, multiple investigations into government corruption and mismanagement, and an extended period of mourning that continues to the present. In Ansan, the 4.16 Memorial Classroom is a museum that recreates the students’ now-empty classrooms, and provides interpretive information about the disaster.

As a Western casual observer, I could not help wondering whether the new South Korean president Suk Yeol Yoon is also wishing that his political detractors could be released and sent packing. While Yoon’s supporters are eager to find cause, blame others and thereby put this episode behind them, families of the 153 young adults killed, the dozens of others injured in the incident, and many other angry people in Seoul are using public displays of sorrow as new fuel to feed their flames of protests, which began in earnest a week before Halloween and have grown in intensity given the deaths and the coverups of official neglect that followed. Korea’s recovery period will not be two hours or two weeks, but probably much longer, before the grief and anger emerging from this senseless disaster abated.