Twin Cities Korean Americans weigh in on survival in a pandemic reality | By Martha Vickery (Spring 2020 issue)

Some people got really busy when the COVID-19 restrictions were activated in Minnesota. Others suddenly had nothing to do. Overnight, live performances were called off, and restaurants and other services were closed, except for those that could do pick-up or delivery. Some hospitals got busy, others went quiet, waiting for an onslaught of coronavirus patients that may or may not arrive.

In this maelstrom, regular Korean Americans were trying to do their work, although work during the new pandemic reality looked very different. It was a very local group contacted for the following; some are previous interviewees for KQ stories, others are KQ contributors and friends. Their stories reflect the realities of teachers, health care workers, artists, and restaurant workers nationwide who in March found themselves in a very different world than the one they were living in February.

Teaching and learning from a distance: Twin Cities instructors and students finish out the year with a bare-bones version of school

Korean American teachers and professors in the Twin Cities were scrambling in March to get a distance learning program that is broader in scale and more complex than ever attempted. For public school districts locally, it was a longer spring break than usual, to give teachers a full two weeks to get the online learning program built and operational.

Students from kindergarten to college lost time in their school year, and hastily-invented on-line learning systems are now only barely replacing the sophisticated human interaction between students and instructors that happens in school and college.

Elementary middle school teacher Laura Sharpe was in online meetings with colleagues trying to hammer it all out during the last half of March. Sharpe works in Roseville as a music teacher for kindergarten through sixth graders, and teaches piano privately at her home. Both jobs changed overnight.

“It has been a marathon,” Sharpe, a Korean adoptee, said of the process. The staff met intensively, trying to adjust the program so that students can easily use it, and staff can make the correct curriculum available. There were many worries, Sharpe said. “How to get resources to parents without overwhelming them” was one of them.

Additionally, it was important to have a consensus on how much to expect of students. “I was telling coworkers that we’ve really got to think hard about what we are trying to accomplish here.” Arts was one of those things that had to take a back seat during this education emergency. Just keeping students somewhat on track with basic education goals for the year was going to be difficult enough.

Other smart minds went on to invent a program in a few days to get breakfasts and lunches to students, through either delivery or pickup. Also within days, a day care program was popped up for children of essential health care workers. “We have about 50 at our school, in five classrooms, with 10 kids per classroom at six-feet distance. All the planning in the last 72 hours has been incredible.”

Next came the really tricky part —- to get students to participate in their on-line education. This is particularly difficult, Sharpe observed, for certain children living with daily trauma. “They are home with parents who are unreliable. They are around people who are not always safe. The people who are reliable in their lives are us,” she said.

Other parents are simply working all day and coming home exhausted, and kids are home alone. These parents cannot participate in their kids’ learning. She knows there are some kids who will be absent from the distance learning program —-they mentally checked out long before they were sent home from school, she predicted. But the team of teachers have to try, and have to strive to make opportunities for learning equitable. “That’s the powerful thing about teaching, that you do care about every single one of them,” she said.

Even though she is stuck at home now, she said, “I am still thinking, ‘oh my gosh, what are they doing right now? I hope they are OK.’”

Sharpe is also supervising the distance learning for her three sons, age 14, 12, and nine, and her four-year-old daughter, who has autism. The four have many levels and styles of learning. She gets it, Sharpe said, if parents are overwhelmed by helping their kids learn from home. Her daughter, and other kids with special needs, are supposed to be learning according to an individualized education program (IEP), according to state guidelines. “It’s going to be interesting to see how they will try to implement that,” she said.

Teachers nationwide are learning fast how to do on-line learning better, Sharpe said. It will be an experience to put in the record books, she predicted. “We are making history, and I think we have to be gentle with ourselves and not throw out our failures. We have to learn from them and see how we can improve.”

Brad Tipka, principal of Sejong Academy in St. Paul, Minnesota’s only Korean language-immersion public school, said in late March that they had just delivered (or had parents pick up) I-Pads for distance learning, along with every students’ contents of their desk to equip them for their new distance-learning. As long as everything is working, it’s fine, Tipka said, “but if there is a mike not functioning or something else wrong, we can’t go over there and fix it,” he said.

The teachers, almost all of whom are Korean Americans, have been meeting and planning out how the on-line school day will go. Teachers and students will meet virtually twice a day, he said with Google chat session, in Korean for students who are advanced enough. Other work will be a combination of videos, online worksheets or other activities on line.

“One of the big challenges is, of course, with language, you need to listen and repeat, so we will be doing some live sessions for that. But that’s where the technology becomes a little tricky, with the microphone, background noise and stuff like that,” Tipka said. “Teachers know that it is supposed to be a regular school day as much as possible, that they have to keep trying to engage the students and be interactive.”

Since kids are on line many hours a day in a normal week, “being on line at school for six hours a day is probably not a big deal,” he said. “But actually being on line and doing school work —- they are not completely used to that.” Teachers will email or phone students who need help, and students who have not done anything for that day, and ask what is going on. There will be a system of taking attendance to ensure students are at least doing the work.

“It will be a full day’s work for teachers,” Tipka said. “Maybe even more work than normal, like if they get 10 emails and need to respond to each one.”

After Minnesota’s Stay-Home order expires May 4, the students are scheduled for a two-week break. The eighth graders customarily go to Korea during the break, but not this year, Tipka said. It is a big disappointment for the kids who have been hoping for it and fundraising for it for years. After the break, will it be worth it to come back to school for a couple weeks after the two-week break? It was all up in the air at the time of the interview.

Other than pre-K and kindergarten, Sejong will “go paperless” with assignments to have the safest and fastest interactions. When bus drivers deliver the meals, they can also pick up younger students’ finished paper assignments when necessary.

The state has suspended end-of-year testing, which allows for some flexibility for learning goals, Tipka said. On the other hand, there will be no make-up for it. Distance learning is the only school for the rest of the year, and Tipka hopes that students will feel just enough pressure to keep them doing their daily work, and not falling behind. “It will be a big challenge, but to the best of our ability, we need to teach the grade level standards students would be getting in person.”

High school reduced to its boring basics

Aidan Ma, an 11th grader at Eastridge High School in Woodbury, found out in the middle of spring break that the whole district would be off until March 30, when they would go on distance learning, likely for the rest of the school year.

Converting from in-person school to distance learning is not a big deal at his high school, he said, since students have been filing assignments and taking tests online, using a program called Schoology, for about two years. There had been some early hints from the district about the move to on-line school, because parents received an email asking about the family’s home equipment, such as access to wi-fi, that would make distance learning doable, he said.

As easy as it will be for many high school students to keep using the school work software they have become used to, the curriculum part of high school is only the bare bones. The human interaction is conspicuously missing, he observed. “I think I will eventually miss the teacher interaction. If you don’t understand an assignment or a problem, it is kind of hard to voice that through email and typing all the time. It is much better when you can ask face-to-face.”

Other concerns for him Ma said, is what will happen with the standardized testing for advanced placement (AP) courses and how distance learning will affect AP students. Ma plays baseball, so the cancellation of the Eastridge baseball season is a disappointment. Also, at the time school was cancelled, it was the end of the basketball season when their team was about to go into the playoffs; that was all cancelled too.

Ma said he feels the worst for seniors, whose graduation activities are now off. He and his classmates have been reduced to interacting on social media. “All the social aspects of high school, we feel like we have been robbed of that. We can still keep in touch, but can’t really hang out. So, it’s not the same. It’s actually pretty boring now.”

Lectures get a little flat with no Q and A

Joanne Lee took a new job as a history professor in January at Century College, part of a state system called Minnesota State Colleges and Universities (MNSCU). She was looking forward to teaching her Asian history classes to a new group of students, a high percent of whom are Asian Americans.

Like most school districts in Minnesota, the MNSCU spring break also extended two weeks longer than usual to allow the faculty to prepare how to deliver class content 100 percent on line.

“For some instructors already doing on-line teaching, it’s no big deal, and for others it is a big change. I am kind of in the middle,” Lee said.

While she was trying to figure out how to deal with this structural change, her college-age daughter moved back in, and 12-year-old son got an extra-long vacation due to a St. Paul teachers’ strike followed by schools closing and an additional two weeks an extra couple for teachers to plan for distance learning.

Lee said she started her class planning process by thinking about what her students needed, rather than what technology could provide. College students are also employees and parents. The start of the pandemic crisis left many of them dealing with kids at home, providing care to older family members, or arranging hours for a job providing essential services.

The pandemic is motivating faculty to learn how to teach online, Lee observed. Some faculty are skilled at online teaching techniques, others don’t have a clue. Most students, however, are already conversant in all the necessary technology. The problem for students isn’t technological; they have other challenges.

She took a poll of the students in her current class, entitled Southeast Asian and the Vietnam War. Some replied that they did not have a microphone or camera, or they were dealing with a slow internet connection. Other students said they were working unpredictable hours, and needed some flexibility in when they could listen to a lecture. “So I decided not to go on Zoom. I decided I was just going to record my lectures and then put a link on line,” Lee explained. These days, twice weekly, she puts the next lecture on line. She structured it so that students can access it by first passing a quiz on that week’s reading assignment.

There is a loss for her and the class in not seeing students face to face, Lee said. “Now that I am recording the class, I’ve found that a class that would take an hour and a half with participation and discussion will only take 30 minutes now. So, definitely, it is not going to be the same full experience for them,” although students are invited to email her with questions. The loss is mainly in not being able to talk to one another and to hear and discuss all the questions, she said.

Guidance from administration to faculty is to concentrate on core goals of the course and “for us to just be really understanding, help students to finish out the course, get the credits, and in some cases, to graduate next month,” she said. At the time of the interview, Lee said there was some uncertainty as to whether classes would be able to end on time or have to close early, so faculty were advised to trim everything possible from the schedule.

Lee was excited about this first class at Century, especially because some of them were from families that had been profoundly affected by the Vietnam War. “I had group of 20 students and they were all with me, and all doing so well. I was just so proud of all of them.”

Lee reluctantly cancelled a final project —- to interview and report on someone who lived through the Vietnam War. In the light of COVID-19 protocols, the assignment was not equitable for all students, because it would potentially require an in-person interview. It was also in addition to the minimal History Department’s standards for the class.

“Some of the students were already telling me who they were going to interview, and most were going to do someone in their family, if they are Hmong or other Southeast Asian students.” Other students had planned find and interview strangers; Vietnam veterans or people who had been in the resistance movement against the war. “They were all going to be so great and I was so excited …but I had to cancel the whole project because they can’t really interview. It just broke my heart because that kind of project was really why I took this job.”

Recently, Lee wrote in a follow-up email that she added an online discussion forum to the class, and during the discussion for The Hmong Secret War in Laos segment, “I asked if anyone who had already conducted their interview would be willing to share a little bit about what they learned. I was blown away by the three students who shared their grandparents’ experiences crossing the Mekong River, and their parents’ experiences in refugee camps in Thailand.” Memorably, one student, whose grandfather had since died, “said the project gave her the opportunity to talk to him for the first time about his experiences in the war, and how grateful she was for it,” Lee wrote.

Permanent social distancing? A necessary but sad option for churches

Pastor Jay Jeong of Mounds Park United Methodist Church in St. Paul said he was prompted early to take action on alternatives to in-person church activities, mainly because of his habit of reading news media originating in South Korea. “I was reading what was going on in Korea while the U.S. was doing nothing, although medical professionals were shouting out warnings,” he said.

In South Korea, coronavirus control measures started in early February. “Starting then, I started thinking ‘we really should not be moving around like this’ —- like people still packing into restaurants while the virus was starting to spike in the U.S.”

One of his congregation members, a nurse, encouraged him to take action. “She said we should cancel worship and meetings right away —- don’t wait.” A hasty meeting of the executive board took place, and the March 15 service was cancelled. The next Sunday, March 22, they went online with their worship service. For Palm Sunday and Easter Sunday, the church was quiet and online services have continued.

Sitting by himself in the old sanctuary, stained glass windows converting the rays of sunset into a glowing display, Jeong said he is not optimistic that the pandemic will resolve soon. Even after the initial resolution, it could return in smaller waves of contagion. Therefore, online worship may be needed for much longer than the end of Minnesota’s Stay-Home order due to expire May 18.

Photo by Stephen Wunrow

He is also concerned that their mostly-elderly congregation members should not be coming together in person even if they have official permission to do so. “We are still searching for what’s a good option for them, but right now, the best option seems to be a phone call,” he said. “They really don’t use internet, computers or email services.” For now, he said, the best way is to send out a monthly letter by postal mail, and make personal phone calls.

Two discipleship groups, and several committees related to church operations, are meeting by conference call —- it seems to be the most accessible option for the whole group. The senior members miss the interaction, he said. For some, it’s part of their social life, and during a normal week, people often stop by the church office to chat.

Jeong feels that to be a good leader, he has to battle a lot of misinformation people hear on TV. “As pastor, I should be able to tell them the facts. I know it is frustrating, but I feel I need to protect them from untruthful encouragement or untruthful hope, so that they will not be in danger,” he said. He is coaching his flock to stay home and stay safe. If a vaccine is developed soon, life may go back to normal, but that is the most optimistic scenario. “Professionals are saying that maybe some part of our lifestyle may be permanently changed.”

Adjusting to long-term social distancing is a sad idea for pastors and many others who draw strength from worshiping together. “Thinking about the past, the first thing I miss is hugging and welcoming people after worship. I love to do that,” he said. “Even having a conversation with strangers in the hot tub at the YMCA! Will we be able to do that again? I don’t know.”

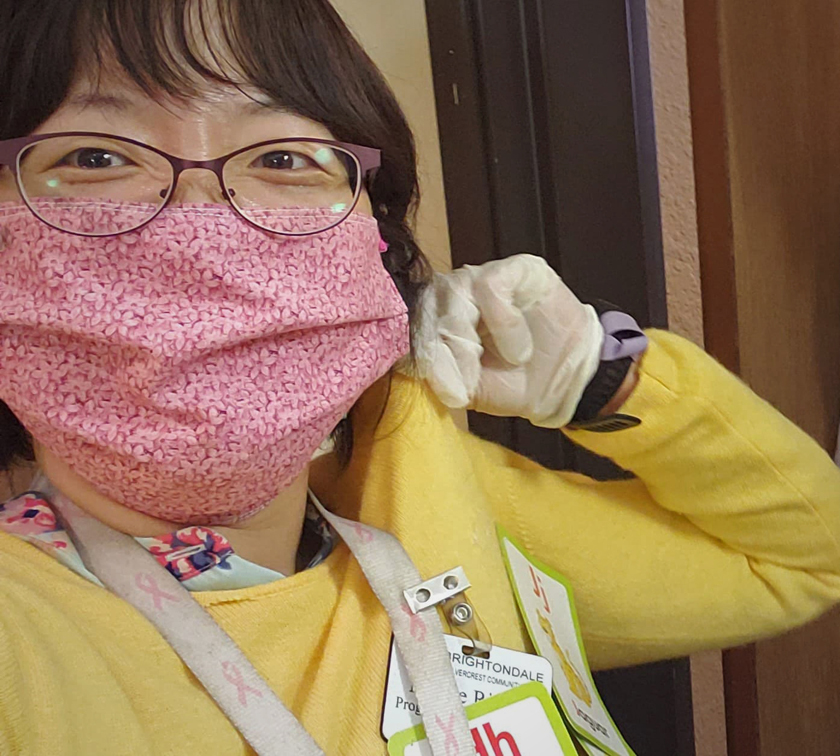

Unsung health care workers do their part

The essential workers, the ones we should be clapping for every night at 7 p.m., include Nicole Ritchie and Dr. Mike Park. Until recently, they and others with positions in health care and health services may have thought their jobs were rather ordinary. Then came the pandemic.

Ritchie has been working as an activity director in a residential senior center for almost three years. Activity directors provide enrichment for the residents, to help them with entertainment, relaxation, and fulfillment of personal goals. In the past, Ritchie would invite groups of residents to play games, watch performances and talks, and engage guided exercise, among other activities. She also provided one-on-one help. But now, with social distancing, group activities are no longer possible.

With no group activities, and no visitors allowed, residents are mainly confined to their apartments now. These days, Ritchie stops by individually, and stays in the doorway area of each apartment. She chats and asks each person if she can help them do a chosen activity. She encourages them to walk in the halls, and more recently, since the weather has improved, she can take a small group, staying six or more feet from each other, for an outdoor walk on a paved trail.

There are about 45 residents at the assisted living unit where she works, so there are lot of visits to get through in a day. It is challenging her problem-solving skills, she said, but there are some benefits. “This is giving me a chance to talk to residents individually, especially those who tend to be more introverted,” she said. She is doing log entries for each resident on what activities she tried and whether it was successful. She asks them to tell her what she can do better the next time.

The positive part of this time, Ritchie said, is the staff’s relationship with residents is growing. “I think that, when this is all done, we will have a greater and closer rapport with our residents.”

Since they cannot receive visitors right now, Ritchie is helping residents communicate with friends and family. For now, they are using the phone. Plans were in the works to get Ipads for the residents, and Ritchie will help set up video chats with their family members. Families also bring gifts, cards and supplies to their family member, which are delivered to their rooms, she said.

When she and other staff come to work, they have to report if they have any symptoms of illness. They also meet weekly with nursing staff to review protocol on how to protect themselves and residents against contagion, and what current recommendations are from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). So far, the place she works has been fortunate. No one has had COVID-19, “but we always talk about what would happen if someone had it,” she said.

Ritchie said she and other staff are taking extra precautions away from work too —- not congregating in groups, and not going to stores often. She takes her temperature every morning and records it. When she brings groceries or any new items into her home, she sanitizes them. “When I am tired, and I want to skip a step, I think of the residents I want to keep safe,” she said.

Recently, the management gave her a letter stating that she is an essential health care worker, in case she should ever be questioned while she is commuting to and from her job. She hasn’t needed the letter so far, but it has served another purpose in giving her a sense of pride. “I never thought of my job as an essential one,” she said.

Michael Park is not a first responder, but he and other non-emergency physicians have had to change everything about how they function to meet the potential challenge of COVID-19 patients filling up the beds at the University of Minnesota Medical Center.

In a normal week, Park does neurosurgery, mainly deep brain stimulation procedures to treat epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease, and other neurological conditions. Although some neurosurgery is essential, most is elective, he said. “These conditions are not life threatening and postponing them will not be detrimental to the patient’s health,” he said. “Also, the population requiring these procedures are typically older, from 60 and up. They are at higher risk for COVID-19, so the less exposure they have, the better for the patient.”

An executive order from the Governor’s Office went into effect March 23 that all elective surgical procedure should be postponed until further notice. “After that, pretty much all my surgeries were cancelled or put on hold.” Park explained that the order is intended to keep hospital beds open, reduce the use of protective equipment, and “especially to reduce the use of ventilators because a lot of our procedures require ventilators,” he said.

His neurosurgery unit also got together to invent a rotation that would ensure there would be continuity of service for patients who need neurosurgical care. The rotation of smaller teams is intended to ensure there will still be a neurosurgeon in another team in case one or more members of a team is exposed to COVID-19, and needs to stay home.

“You hear about hospitals in California or New York being pushed to the limit,” he said. It probably won’t happen at U of M Medical Center, “but we have to be ready for that, and I think we are doing what’s necessary to be ready.”

The result of this change in routine is that the hospital is now quiet. Even the commute into the hospital in the morning is easy. Staff is limiting contact with others, so everything from ordering supplies to interacting with other health care providers is done on line.

For Park, the big avalanche of work will come when the order against elective procedures is lifted. All the patients who had to wait will be lined up. “It’s a little like watching the dirty dishes pile up in the sink,” he joked. “You will have to do them eventually, but you can’t get to them right now.”

Getting people around the table is off for now

With a brand new vertical banner in front of the store, with the word DELIVERY in all-caps, and an on-line logo that quips “Keep Calm and Carry Out,” it is apparent that Bap and Chicken in St. Paul is open for business despite the pandemic, although its business model is very different than the one Korean adoptee John Gleason had in mind when he opened the Korean-themed bar and restaurant in mid-2019.

While some business owners are busily adapting to a business model that will keep the lights on and feed people, others have shut their doors to wait it out, leaving staff unemployed for an unknown amount of time.

Gleason is in the crazy-busy subgroup. Working along with the staff, Gleason is multi-tasking, adding sentences like “do a fried egg,” and “that one gets rice,” during the interview.

He has also put energy into promotions. “I have tried to make FB and Instagram more of a fun-type thing, and want to be creative about how I talk about the carry out and delivery.”

On one Facebook video, Gleason does a goofy version of a mukbang, or (very Korean) online video of someone eating, except that he taste-tests Skittles while talking about spring carry-out and delivery promotions. On another Facebook performance, Gleason promotes his burger “pop-ups,” a carry-out option he offered in collaboration with the St. Paul-based 14 Spice seasoning company. In painfully-bright orange plaid pants, Gleason asks customers to dress up for their carry-out or delivery dining experience.

The menu includes happy hour options, which due to a special legislative act, can now include carry-out beer and wine. They are also trying a carry-out date night combo, and a family-style meal for four, all at set prices. In honor of Cinco de Mayo, the May pop-up menu will include tacos. Kids can still eat free one day a week “and we trust people to have kids that are real,” he joked.

The beer and wine carry-out is still new, and not many people are buying it yet, he said, although they have discounted the carryout alcohol from the normal restaurant prices.

Throughout this crisis, Gleason said he has tried to do what is best for staff, and at the beginning, it looked like laying them off and making them eligible for unemployment was optimal for them. These days, he is adding hours back for employees, while they are still paid the balance of their unemployment. Bap and Chicken was at 40 percent of normal staff at first; now it is up to 80 percent of normal.

Gleason is putting in 12 to 15 hour days. He is also reducing the options and complexity of the menu to make it easier to get food out the door. “We are trying to stay positive every day,” he said, “and seeing what we can do to not only be creative with marketing, but being creative with our expenses too.”

Putting away her rolling pin for now

Emily Marks was named top pastry chef in the Twin Cities in 2018, and is a manager at Bachelor Farmer, a fine dining restaurant and event venue in Minneapolis, which shut its doors March 16. These days, she is accomplishing a list of jobs that have been accumulating at home, including preparing for a big gardening season.

Between all the businesses of the Bachelor Farmer —- café, events staff, dining room, Marvel Bar, and the apparel store Askov Finlayson, there were just under 100 employees to lay off.

The business model of the Bachelor Farmer was not set up to do take-out and delivery —- it just wasn’t worth it to convert to that, and at the same time to make sure the staff was safe, explained Marks, a Korean adoptee. “It’s hard though, being part of a team who love to cook and to serve other people, and we don’t get to do that anymore.”

Managers worked for a few more days after closing, because there were a lot of things to secure for a long-term closure, including lots of perishable foods to deal with. “We donated a lot of food to employees that last day, and anything we had left over went to Second Harvest Heartland, that our chef is working with, so meals could be made and distributed to people in need.”

Some Bachelor Farmer chefs joined up with Chowgirls Killer Catering and other shuttered restaurants to collaborate with the food charity Second Harvest Heartland to form the Minnesota Central Restaurant. That group is preparing more than 10,000 meals per day for pick-up through the Loaves and Fishes program, which normally operates free dining sites in the Twin Cities area.

Marks is just staying put for now. “I’m trying to see the positives in this. It is hard for a lot of people, but my husband is still employed full-time working at home. And I have plenty of projects at home I was never able to get to because I worked all the time,” she said.

Instead of creating pastry, Marks said she is starting garden plants– peppers, tomatoes, herbs and greens —- to give to friends and family for their own gardens. Marks has a large backyard garden, and regularly starts plants in the early spring. She just did a lot more of them this year. “I have a very large back yard, and I have decided to make the most of it.”

No audience, no stage, no cast or crew —- Korean American actors focus on the positive and hunker down

Actors Katie Bradley and Sun Mee Chomet, both seen frequently on Twin Cities stages, are both chilling at home since all local performance venues shut down due to the COVID-19 pandemic during the third week of March.

This shutdown constitutes a widespread layoff of artists and performing arts-related workers in the Twin Cities. According to Joanna Schnedler, executive director of the Minnesota Theater Alliance, 549 people locally are members of the Actors’ Equity Guild, the union of professional actors and stage managers. The majority of professional actors are in the Guild, however, there are additional non-unionized actors.

The Twin Cities is second only to New York City in its percentage of the workforce employed in theater companies. While New York has three times the national average of theater employment, the Minneapolis/St. Paul area has 2.4 times the national average, according to a 2017 Creative Minnesota report. A 2018 city of Minneapolis report estimated that there are 2,933 Asian American creative workers in Minneapolis, or 3.6 percent of the city’s creative workforce.

“Chilling” may be a soft verb for what is a very anxious time for performing artists in the Twin Cities right now. Bradley and Chomet, both Korean adoptees, are restructuring their lives for a short term sabbatical to rest, plan, and pursue creative activities (see the poem by Chomet, this issue p. 59).

Bradley was at the Indiana Repertory Theatre in Indianapolis acting in Murder on the Orient Express at the time that production closed. She left March 17, drove back to Minneapolis, and since then has only been to the grocery store and out for other necessary trips. For the last 15 years, Bradley has acted locally and regionally in live theater, and also teaches acting.

“The Indiana Repertory staff was wonderful, and communicated with us as much as they could,” about the impending shutdown, she said. They attempted to keep going with limited seating and people spread out —- that went on for a few days. On the last day the play was open, a production of the play was taped with a minimal audience for a possible pay-to-download option.

During the last few performances, she said “I would get all teary-eyed looking at the faces in the audience, knowing that it was all shutting down.” At the last live performance, the audience gave a standing ovation, and the actors also clapped for the audience —- a meaningful gesture for both.

In touch with friends in the arts since returning, Bradley said that many have told her they have lost all their gigs, some at least until the summer; some for a whole year. Actors are always dealing with the unpredictability of their profession “but we always know that theaters are still going and classrooms too, for those of us who are teaching artists. But, our job is to get in front of a lot of people crowded into one room. We won’t be able to do that now, but for how long? That is the terror, of not knowing.”

Theaters are maneuvering their seasons for later on. “Theater Mu, which I am heavily involved with, is trying to think about a viable schedule now,” Bradley said. “Companies are thinking about smaller casts, or not doing as many shows. I think the larger companies will be OK. But the mid-size and smaller theaters are the ones I worry about not making it through.”

Another disturbing reality for Asian Americans is the anti-Asian sentiment which emerged because of the epidemic’s beginnings in China. “Being Asian right now is a little terrifying for me,” she said. “I went to the store for my parents, and mentally prepared myself for what I would do if someone approached me and said something [anti-Asian] to me, and it sucks that I felt I had to do that.”

Bradley said she facilitated a recent Zoom chat with the Asian American arts community, at which she invited people to talk about any racially-motivated occurrences around the COVID-19 pandemic. A younger Asian adoptee started crying —- the person had received disturbing and hateful messages. “The person’s [adoptive] family was not supportive” and the young actor had been very upset by the experience, she said.

At the moment, Bradley said she is doing more running, cooking, fiction reading, and preliminarily planning for the fall. She will have a part in the Guthrie’s A Christmas Carol this year, and assuming, at least for the moment, that the production will go forward. She would like to plan more, but there are too many unknowns. “We will just see how it goes with the world.”

Sun Mee Chomet, who has also had a long career in Twin Cities theater, was in Twelfth Night at the Guthrie when it was cancelled. She also had to postpone her original movement and dance piece about adoption, to be staged at the Southern Theater in Minneapolis, until next year. Chomet was also to appear in the Guthrie’s Emma, slated for this spring, now cancelled.

The cancellation of so much work was jarring. The world premiere of playwright Kate Hamill’s Emma was to be a lavishly designed and costumed production, for which the Guthrie brought in a team of national designers “and the costumes were so beautiful, and we were getting rewrites every day, and then we got an email March 15 saying everything was being put on pause until they figured out what to do,” Chomet said. The next week, they got an email terminating their contracts.

Chomet has applied for unemployment and some money from a Springboard for the Arts relief fund. She had leased a new office space recently, and is now trying to cancel the lease. She was planning on a break from acting after this summer’s season, she said. Now, she will be living on savings and unemployment. “It feels pretty indefinite as far as the future,” she said. “If push comes to shove, actors have always worked odd jobs, but for the moment, I am really fine not leaving my home very much.”

Interesingly, the Guthrie did not pay actors anything but three days wages at first, because of an Actor’s Equity Handbook clause citing an exception if the show cancellation is due to “an act of God,” Chomet said. The cast of Twelfth Night wrote a letter to Guthrie management asking for more pay for the cancellation and as a result got one additional week, she added. It is now a matter for the Actors’ Equity Association to work out.

She has worked out some positive activities —- Korean language lessons from a friend in New York, and a workout schedule with her brothers, both on Zoom. “I want to use the time well, rather than just squander it,” she said. She wants to rest, meditate and plan.

Working with the theater group Ten Thousand Things, that reaches out to women’s shelters and high security prisons, has given her a grounded perspective on this experience, she said. “Even though we are stuck at home, we are still free. We still have free time. People work hard towards their retirement to try to have this kind of time.”

“Don’t get me wrong,” she added, “I spent first week super-depressed and watching like 25 hours of Downton Abbey! …But, I know that the only way to be a positive person and give out positivity in the world is to foster it, and work towards it.”

Another reality she has absorbed through Ten Thousand Things is “life is more important than art. …and there are things more important than plays. We will come back, but this is one of those times.”

Korean Quarterly is dedicated to producing quality non-profit independent journalism rooted in the Korean American community. Please support us by subscribing, donating, or making a purchase through our store.