Five senior Korean Americans pen their recollections of a boyhood they barely survived | By Martha Vickery (Summer 2020 issue)

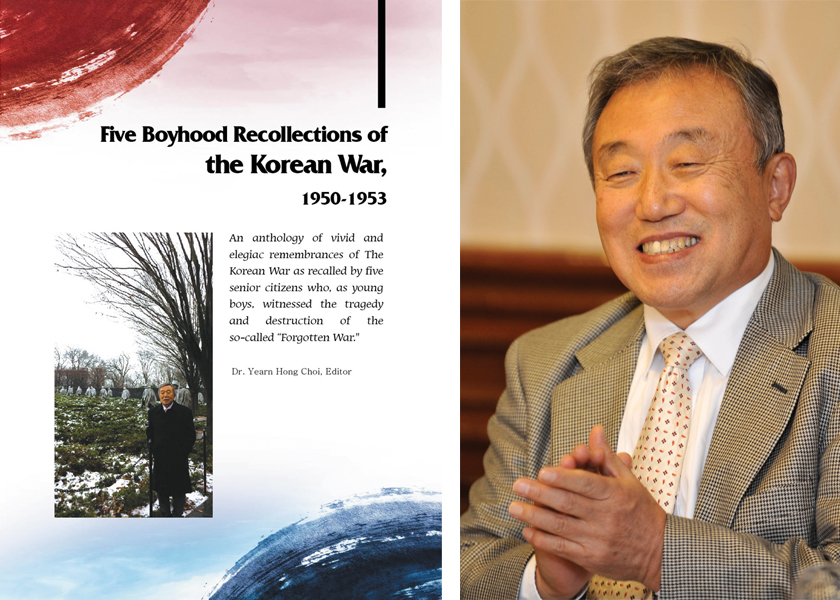

(right) Anthology editor, and poet, Yearn Hong Choi.

A Korean American poet and writer has edited an anthology of five remembrances of the Korean War from the perspective of childhood, entitled Five Boyhood Recollections of the Korean War: 1950-1953.

Editor Yearn Hong Choi said he is the youngest of the contributors to this volume; he was nine in 1950, and is now 79. The oldest contributor was age 18 when the war started. Korean Americans old enough to remember the Korean War were all children when they went through the experience. “When we are gone, there will be no one will be a witness to the Korean War experience,” the editor said. “That’s why this book may be a significant contribution to Korean War historiographies.”

Common among the stories, Choi said, is that “the Korean closely- tied family network saved their lives during the war.” For example, contributor Hong Kyoon An’s mother worked for the local neighborhood office, where the organizers knew when young men would be rounded up for forced draft into the military, he said. That knowledge was key to saving her son from the wholesale conscription going on during that era. “She was a kind of double spy!” he said. All of the contributors are the editor’s local friends and acquaintances; every Korean American of this age group has a family survival story that is seldom told.

The editor contributed a short memoir and several poems to this slim anthology. In a short memoir, he remembers his father going into hiding and his mother bringing him to an uncle’s house north of Seoul, from which they waited out the occupation of Seoul in relative obscurity. He recalls the vista from the top of a wrecked tank on a hilltop. He would climb up there every evening to watch for his mother appear on her way home from a marketplace where she sold vegetables. He was later relocated to his grandfather’s rural home further south, and eventually, his father reappeared, evacuating the family south to Busan, where they survived the rest of the war. The editor also added some short essays and poems to the anthology, selected from his Korea Times columns related to the Korean War.

Hong Kyoon An, in his essay Ninety Days Under the Reds: June 25-September 29, 1950, describes a more detailed and nuanced view of experiencing a military occupation from the perspective of a high school senior. His essay describes how he perceives his parents alarm as they try to find food and call in debts in the days after the June 25, 1950 incursion of North Korean troops over the border of the DMZ. His parents decided to wait, not knowing whether to flee Seoul or stay. In the end, they split the family and hid in a couple locations, but never evacuated to Busan as other South Koreans did at that time.

There are interesting details, such as how a military parade in advance of the mobilization showed off a few unarmed aircraft (the extent of the air power of the country at the time), and a military marching band, which notably, played unfamiliar songs on unfamiliar instruments, like the sousaphone. The South Korean military used the U.S. military band because it had no band, and no marching songs. He later decides that the North Korean army has far better revolutionary songs and catchier lyrics, in fact, better propaganda of all kinds, than the South Koreans.

Waking up one day, he sees tanks sitting silently in the middle of the street, flying an unknown flag, the new North Korean flag, and concludes that his city has been occupied. He was confined to the house, but sneaked out one day, and remembers chilling details of Seoul city streets under occupation, with empty streets, empty store shelves, and propaganda posters everywhere.

An’s mother answers the door one day to find her son’s former classmate, who urges her to send Hong Kyoon to a “rally” at school the next day, although the schools were still closed. An successfully avoided the search parties that rounded up young South Korean men and forcibly conscripted them into the so-called volunteer army. This was mainly due to the determination of his mother, who guarded him, and hid him in a woodpile, a small crawl space, and other places. She also got a job working for a neighborhood office for the specific purpose of finding out when search parties would be sent out. After the North Koreans are chased north again and the city was free from occupation, An reflected, “And in our own way, my family —- my mother in particular —- won the battle.”

After the Chinese army invaded in November 1950, An walked from Seoul to Busan to join the South Korean Army. He served for 10 years, leaving as a captain, and immigrated to the U.S. as an undergraduate student at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. He later earned a graduate degree in international politics from George Washington University.

Chang Wuk Kang, a Baltimore, Maryland psychiatrist, was a junior high school student in Busan, the southernmost port of Korean Peninsula, the only area that was save from Communist invasion in the South during the War. From a boy’s perspective, his essay documents the transformation of his city, and the mix of people who were forced into the city at that time.

Kang describes a young boy’s observations of a suddenly overpopulated city, teeming with an influx of American soldiers and other United Nations forces, together with their arms and supplies. He remembers how his own knowledge expanded as he walked the streets of that diverse city. “I especially liked the comics that were thrown out by the GIs. My friends and I would pore over these comics, and I was able to use a dictionary to translate the unfamiliar words I read in the comics, my first attempts at learning to read English.”

Jai Won Choi, writing from the vantage point of a 12-year-old in 1950, shares personal boyhood memories in his essay A Memory of the Korean War of wartime wonder and loss, from confronting the death of a friend who was one of the most promising young men of his home town, to the survival from his own near-death experience. He writes warmly of an idyllic village life upended by the tragedy of war, and of the close-knit family ties that helped his family survive the war.

Choi, a graduate of Yonsei University, also earned degrees from California Baptist University and the University of Minnesota. He is now retired, but formerly worked at the National Center for Health Statistics at the Centers for Disease Control, and was Professor of Bio-statistics at the Medical College of Georgia in Augusta.

Soon Paik, then an 11-year old elementary school boy, contributed a short essay The Korean War: Destruction and Hunger on his recollections of the War. A North Korean agent arrested his father and sent him to North Korea, and the family never heard from him again. His family of 12 lived in a small town south of the Han River, with virtually no food. His memories of severe deprivation shaped his adulthood. His family traveled to Busan to escape the invasion from the north by spending two weeks inside a grain car of a southbound train. He is a graduate of Seoul National University and West Virginia University, and a retired economist who worked for the Department of Labor.

Editor Yearn Hong Choi is a member of a Washington DC-area Korean American poets and writers’ group. A graduate of Yonsei University and Indiana University, he taught public policy and administration in the U.S. and Korea from 1972 to 2006. He is a longtime contributor of book and poetry reviews to Korean Quarterly. The collection Five Boyhood Recollections of the Korean War: 1950-1953 is now available from Amazon and Kindle. A Korean translation of the book is scheduled for June 2021.