75 years after the Jeju 4.3 Massacre, Koreans want a U.S. apology | By Jon Letman (Summer 2023)

Jeju Island, a popular vacation and honeymoon destination, explodes in a riot of pink cherry blossoms each spring. But the season in Jeju also reminds residents of a period of tremendous political upheaval and violence known variously as the “April 3 Incident,” or the “4.3 Uprising,” or simply “4.3.” This year, Koreans mark 75 years since the Jeju April 3 Incident.

Seventy-five years ago, this island, strategically located between China, Japan, and the Korean peninsula, was awash in blood and scarred by bullets and fire in one of Korea’s most brutal episodes, all while under U.S. military rule.

In the aftermath of World War II, the newly-liberated peninsula was emerging from Japanese colonization (1910-1945), and Koreans were determined to develop a self-reliant, independent and unified nation. On Jeju, opposition to a divided Korea was especially strong. Three months after the Japanese were ousted, a new occupying force — the 59th Military Government Company — arrived on Jeju with tank landing ships and established the U.S. Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK).

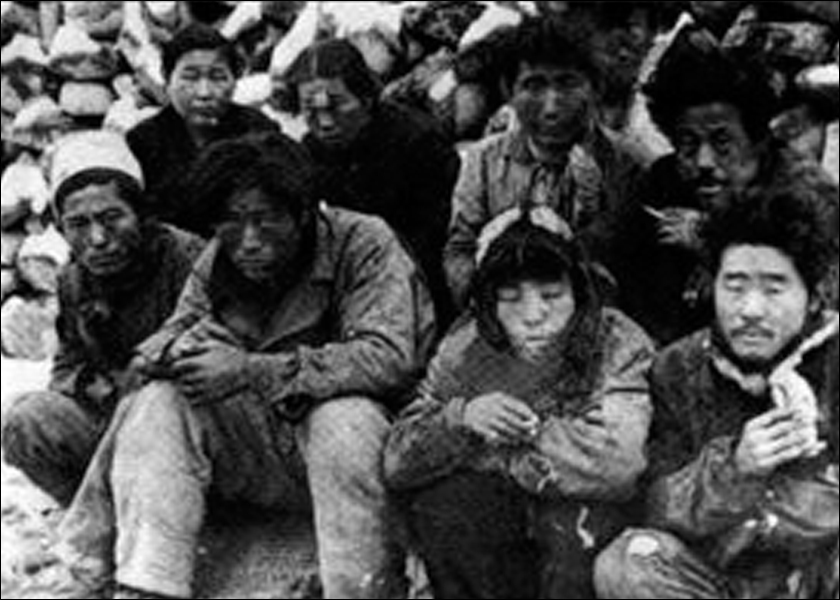

What followed was a chaotic rupturing of Jeju society and a paroxysm of violence that resulted in an estimated 30,000 deaths (10 percent of the population), widespread displacement, and the destruction of some 300 villages and tens of thousands of homes.

In the 1940s, Jeju was a largely agrarian society comprised mainly of independent farmers who grew barley, buckwheat, citrus, and other crops. Immediately after the war, Jeju’s population swelled by roughly 25 percent, as conscripted soldiers, newly-liberated laborers who had been forced to work in Japan, and other displaced people returned. Rising unemployment, inflation, and a cholera outbreak led to heightened social tensions.

Following a poor barley harvest, USAMGIK’s ill-informed decision to impose a highly restrictive grain import policy, and to reinstate Japanese colonial-era grain collection, bred mistrust and led to worsening living conditions and festering discontent. Meanwhile, local groups like the Jeju Island People’s Committee and other civilian groups sought independence, liberty, the preservation of a unified Korean peninsula, and the removal of any vestiges of Japanese colonial rule.

For its part, U.S. military and government authorities were concerned to the point of obsession with countering Soviet and communist influence out of a fear of Jeju becoming a “red island.” Tension on Jeju mounted as the USAMGIK rebuilt Jeju’s police force, turning to former Japanese collaborators (considered by many Koreans to be traitors). The reconstituted constabulary bureaucracy rooted in colonial rule was determined to crush left-wing groups and anyone labeled a communist. A thirst for vengeance was growing among police, military, and people’s committees on both the left and the right.

By 1946, police were clamping down hard on the Jeju Island People’s Committee and other left-wing groups. Demonstrations and mass arrests surged.

As the U.S. authorities expanded Jeju’s police force, doubling it to what it had been under Japanese occupation, right-wing paramilitary groups grew stronger. At the same time, shipping disruptions and grain distribution practices exacerbated food shortages.

While peace and order on Jeju unraveled, the U.S. was also supporting anti-Communist forces in Greece, spawning the Truman Doctrine and a policy intended to contain the spread of communism. Some U.S. government officials compared the Greek civil war to anti-communist containment on the Korean peninsula, prompting Truman to refer to Korea as the “Greece of the East.”

The trigger

On March 1, 1947, Jeju police shot into a crowd at an independence demonstration, killing six civilians. When police went unpunished, the lack of accountability fueled anger. As general strikes and mass arrests increased, the USAMGIK bolstered its support for right-wing forces. Chaos and violence spread as police targeted civilians and suspected insurgents. Arrested people were forced into tiny, overcrowded cells.

On the morning of April 3, 1948, armed rebels attacked a dozen police stations, igniting a period of some of the most wanton violence in modern Korean history. Although USAMGIK was the ruling authority at the time, it took no action to prevent the murder, rape, torture, and destruction that swept across the island. During the autumn of 1948, violence raged as civilians were killed with bamboo spears, and entire villages were razed.

Fearing targeted reprisals, villagers fled beyond the five-kilometer coastal area into the island’s interior no-go zone to hide in caves, giant lava tubes, or the forests of volcanic Mt. Halla. At what are some of Jeju’s most popular tourist attractions today, civilian massacres were carried out.

At the heart of the 4.3 Incident was widespread opposition to a U.S.- supported election scheduled for May 10, 1948, that would create a separate Korean government in the south, dividing it from the north. For the U.S., the election was the most important event since 1945. Among Koreans in the south, there was strong political opposition to the election. Some 90 percent of those who registered to vote across southern Korea said they did so under duress. Overall, Jeju had the lowest voter turnout in the country, the highest election-related injury and death rate, and the election results were deemed invalid.

Ultimately, a south-only government was formed, the Republic of Korea, headed by U.S-backed Syngman Rhee, South Korea’s first president. In a letter to Truman, Rhee wrote, “…the immediate establishment of an interim independent government in the American zone will set up a bulwark against advancing communism.” Rhee also expressed confidence that the U.S. would be permitted to build a permanent naval base on Jeju following the establishment of a South Korean government.

When the Republic of Korea was established on August 15, 1948, the U.S. military was still in command of Korean forces but refrained from an overt display of force to avoid unwanted attention. U.S. military authorities were in control of and aware of the violence on Jeju, but the priority of suppressing anyone considered to be a communist was paramount.

A robust response

In late 1948, Syngman Rhee was informed that U.S. Secretary of State Dean Acheson wanted guerillas in Korea to be “swiftly eliminated” and that American support would require a “robust response.” According to a U.S. Army G-2 report, between 14,000-15,000 residents of Jeju were killed in 1948. In one mass execution the following year, 249 people were killed with the Rhee’s approval, an event that was all but unreported outside of Jeju.

By September 1954, violence had waned, and restrictions eased, but for decades even mentioning 4.3 was effectively taboo. Those who did so risked being labeled North Korea sympathizers, facing imprisonment, or worse. It wasn’t until the late 1980s that the 4.3 uprising entered public discourse. In 1999, the South Korean parliament passed the Jeju 4.3 Special Law for Fact Finding and Reputation Recovery to establish truth, restore the honor of victims, and provide financial reparations.

In 2003, South Korea’s President Moo-hyun Roh apologized for the government’s role in 4.3. In 2005, Jeju was dubbed an “island of peace,” and in 2013, April 3 was designated a national memorial day. Former President Jae-in Moon called the 4.3 Incident “a historical fact that no force can deny,” but years later, Jeju journalist and author Ho-joon Heo interviewed retired American military advisors who had been on Jeju during the 4.3 Incident and claimed to know nothing about the massacres happening around them.

As the drive for reconciliation has gained momentum, many 4.3 survivors and their families say the time has come for the U.S. to acknowledge and apologize for its role. “The U.S. government’s apology regarding the role of the U.S. military government and the U.S. military advisory group has been delayed,” said Hee-bum Koh, chairman of the Jeju 4.3 Peace Foundation.

Koh noted that in 2018 more than 200 South Korean civil society organizations gathered 100,000 signatures, demanding a U.S. apology which was submitted to the U.S. Embassy in South Korea. Koh points to previous U.S. presidents who have expressed remorse for past acts of injustice or mourned the extreme violence committed by the U.S. and said it is time for the U.S. to apologize for what happened under its authority.

“The families of the victims have been waiting for 75 years,” Koh said “It would be better to receive an official apology sooner rather than later.” He said it would be especially desirable if, rather than just a high-ranking official, the U.S. president offered a word of condolence and took responsibility for the U.S. involvement in the 4.3 Incident.

“An honest reckoning with the past,” Koh said, “can contribute to the development of a stronger alliance between our two nations.”

No apologies

Asked to characterize the role of the U.S. military on Jeju during the 4.3 Incident and about Korean demands for an apology, a State Department spokesperson said in an email, “the Jeju Incident of 1948 was a terrible tragedy, and we should never forget the devastating loss of life.” They added that “as close allies committed to democratic values and promoting human rights, the United States shares the resolve of the Republic of Korea to work together to prevent such tragedies in the future anywhere around the world.”

The White House did not respond to a request for comment.

Heo, who spent more than 30 years researching the uprising for his book “American Involvement in the Jeju April 3 Incident: What the US Did on Jeju Island,” said that the U.S. role in the Jeju 4.3 Uprising is well preserved in U.S. government documents, photographs, and press reports from the time. Heo writes that Truman and other U.S. leaders knew about the massacres on Jeju, but were more concerned with losing control of Korea.

In his book, Heo quotes a 1947 New York Post article which reads: “South Korea’s jails are overflowing with political prisoners as a result of undeclared war by its rightist police on leftist elements […] While American authorities deplore the notoriously brutal police methods, they look favorably on the current campaign because the Communists are the target.”

Heo said there needs to be more awareness of the U.S. role in the carnage on Jeju Island during the months of the uprising among American politicians, scholars, journalists, and the public. Seeking the truth, he said, should not be a means to punish but rather a path toward reconciliation and can serve as a global model for confronting historical injustice and human rights violations.

University of Connecticut history professor Alexis Dudden calls Jeju the “core of the post-1945 conundrum and collapse of what still continues to be called Pax Americana.” She said that Jeju was arguably the precursor to the Korean War, which began after widespread civil conflict and bloodshed had already occurred elsewhere in Korea.

“The Jeju massacre stands as history for what a total blood bath looks like,” Dudden said. “Jeju was huge because the sheer violence was supported by the U.S. military government, pushed under, and denied.”

Dudden called 4.3 a “massacre in plain sight which an open civil society is still grappling with, and it is the harbinger of the kind of violence that we’re living in today.”

First-class strategic importance

Today on Jeju, as they recall the horrors of 4.3, peace activists say real peace remains elusive. Activist Sung-hee Choi says that what took place during 4.3 served as a model for scorched-earth policies in other parts of the world, from Southeast Asia and Central America to the Middle East. She implores Americans to learn Jeju’s history to better understand U.S. foreign policy. According to Choi, the colonial pattern has been repeated countless times. “You frame the people. You divide the people. You target the people. You justify the killing,” she said.

According to Choi, peace activists on Jeju are still targeted under South Korea’s expansive National Security Act, which she calls an oppressive law dating back to the 4.3-era.

She added that the U.S. has retained access to strategically important Jeju, so coveted by the U.S. after World War II.

As recently as early March, a U.S. (Arleigh Burke-class) guided-missile destroyer made a scheduled port call at the Korean naval base on Jeju for what the commanding officer said was to “ensure our forces can operate together effectively and maintain peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific region.” The destroyer’s visit was preceded by the port call of a Los Angeles-class fast attack submarine in Busan. For more than 16 years, Choi and other activists have protested daily outside the Jeju naval base, calling for an end to the militarization of Jeju and the Korean peninsula. (Check out KQ’s coverage of the Jeju naval base issue)

During World War II, Jeju was a staging ground for Japanese air attacks. As early as 1885, Japanese newspapers reported on presumed Russian ambition to control the island, while a Washington Post article the same year called Jeju’s strategic position “of first-class importance.”

On April 26, 2023, President Joe Biden hosted South Korean President Suk-yeol Yoon for a state visit, in part to celebrate 70 years of the U.S.-South Korean alliance. Yoon, who was the first conservative South Korean president to attend a 4.3 ceremony, has also been accused of revisionist policies.

As 4.3 survivors and others continue to demand a U.S. apology, any mention of the Jeju 4.3 history seems highly unlikely to happen, given the U.S.-ROK commitment to bolster their decades-old calcified front against China, Russia, and North Korea.

On Jeju, where the winter-blooming red camellia is a symbol of the victims of 4.3, the roots of a conflict watered in blood have seen the sunlight, allowing the truth to bloom at last. The truth-telling gives Koreans a chance to reconcile with their past. In turn, Americans should take the opportunity to do the same.

Check out KQ’s feature story on Jeju “Dark Tours” which visit massacre sites and gives information to interested individuals and groups.

This article originally appeared in inkstickmedia.com and is reprinted with permission.