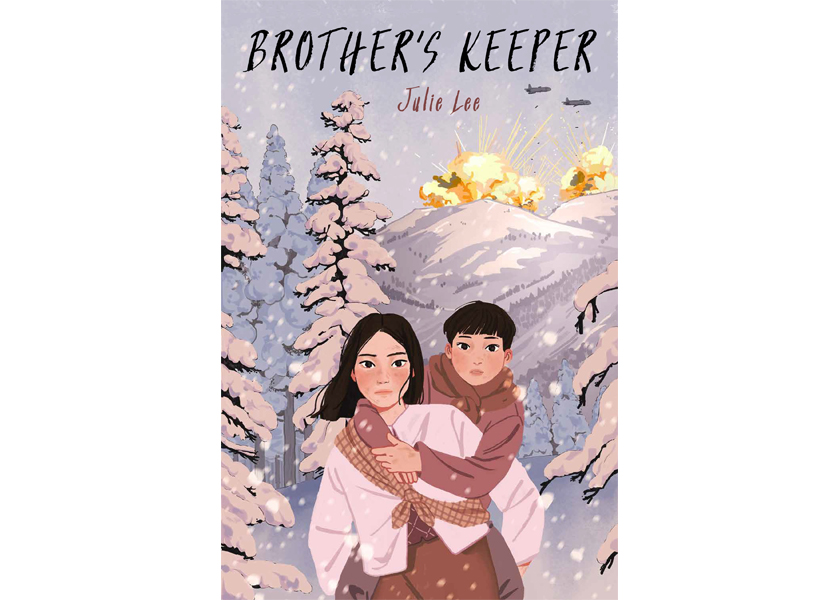

Brother’s Keeper ~ By Julie Lee

(Holiday House, New York, 2020 ISBN# 978-0-8234-4494-6)

Review by Joanne Rhim Lee (Winter 2021 issue)

Julie Lee’s debut young adult (YA) novel Brother’s Keeper begins innocently enough: 12-year-old Sora lives with her parents and two younger brothers in a quiet village in northern Korea. Sora is a smart, studious girl who dreams of becoming a writer someday, but unfortunately her parents have recently pulled her out of school to look after her brothers, the youngest of whom is just a baby. She envies eight-year-old Youngsoo because he is allowed to attend school and read textbooks. She sometimes eavesdrops outside of his classroom after dropping him off in the morning.

Sora has the great misfortune of having been born a girl in a traditional patriarchal society. If she sometimes forgets this fact in a fleeting moment of joy, her mother reminds her that she should not waste time reading books, since she will most likely be married off in a few years and should instead be practicing cutting fruit, cooking and keeping house.

Sora’s mother and her mother’s good friend Mrs. Kim take turns insulting their daughters and praising their sons, with Mrs. Kim pointing out that Sora’s mother has double the good fortune because she has two sons. In contrast, Sora’s father seems to recognize Sora’s intelligence and desire to be more than be a housewife. However, during a dinner with the Kim family, even her father betrays her by insulting her cooking, a comment that Sora understands is expected, but still sees as a betrayal.

The year is 1950, and the two families discuss the possibility of war looming on the horizon. Though the Kims share their plans to flee south before the situation becomes dangerous, Sora’s parents are determined to stay put, as the village is their beloved ancestral home.

Korea was suddenly thrust into war in June 1950. Sora and her family are forced to flee their home, only a few days after they had rejected the Kims’ invitation to join them in their flight to the south. In the early chaos, Sora and Youngsoo are somehow separated from their parents and baby brother, and forced to fend for themselves as they follow the trail of thousands of other refugees moving southward.

At first, Sora and Youngsoo cling to the notion that their parents are just around the corner waiting for them. But as their separation stretches on for days and then weeks, they must accept the fact that they are now on their own.

Sora is smart and scrappy, and knows that if they attach themselves to a young mother and her children, they will be safe and well-fed. This works for a few nights, but then Sora notices that the woman tries to leave early in the morning before they wake up. When Sora desperately chases after her, the woman gives her harsh advice. “Your only saving grace is your brother; at least he is a son who can carry your family name and support you once he has grown. Take care of him; put his needs before your own. That’s how you survive in this world.” The woman’s words echo Sora’s own mother’s painful approach to parenting, but Sora tucks them away.

As their hunger and desperation increase, Sora and Youngsoo do things they would never have considered before: Breaking into abandoned homes to rest and search for food. They find mostly buried jars of kimchi, and though it upsets their stomachs to eat it plain, they must sustain themselves somehow, so they endure the pain and cramping that come afterward.

Finally, on one of their stops, they meet a nice couple who takes them in for a night. Sora has the fleeting idea that perhaps they would be willing to let them stay indefinitely in their warm home, but the husband announces that they only want Youngsoo, and Sora must leave. They don’t have children of their own, and they recognize that a son could take care of them in their old age, but a daughter would just be an extra cost and someday require an expensive dowry. He bluntly says, “It’s the boy we’ll keep. A son is worth more than a daughter.”

Sora and Youngsoo immediately flee the home, but as they travel further south in the middle of winter, their journey becomes more dangerous. Bridges have been blown up to keep the military from crossing over rivers, so the refugees must risk their lives trying to cross over icy patches or swim in freezing waters. Sora and Youngsoo witness extreme acts of kindness, as well as of tragedy and violence.

On top of all their other problems, Youngsoo develops a severe cough, and eventually becomes too weak to walk. In an unbelievable act of strength and selflessness, Sora begins to carry him on her back as they continue on their harrowing journey.

Lee based Brother’s Keeper in part on the experiences of her own mother during the Korean War, and she does not hold back in describing the horror that millions of Korean refugees experienced as they fled south to Busan. In a scene that conjures up chilling memories of the Holocaust, Sora and Youngsoo desperately attempt to board a crowded train car packed with people inside and on top. Though many others are also begging to be let in, a young man standing by the door shows mercy and helps Sora and Youngsoo in. However, once inside, Sora finds herself wanting to shut the door behind her, even though she was just on the other side a moment ago.

In flashbacks, the author fleshes out Sora’s story and describes incidents which lead Sora to make the decisions that she does. At one point, her father gives several bags of rice to their former landlord, after the new communist government confiscates his land and gives it to the tenants, one of whom is a member of her family. When Sora asked her father why he did that, when they clearly needed the rice themselves, he told her that it was always important to do the right thing, even when it is hard.

Lee does an excellent job of conveying Korea’s powerful but painful history to young adult readers. Sora digs deep to find the strength she never imagined she had to get herself and her brother through the ordeal of their lives. They eventually arrive at the home of her uncle in Busan. A long time before this moment, her father had ordered her to memorize it, and she never forgot it.

If this seems unbelievable, I can vouch that my own father did the same thing as he fled south in 1950. He arrived alone on the doorstep of his childhood friend, whose address he had miraculously memorized years earlier.

A less daring writer might neatly wrap up the story with their safe arrival of the two siblings in Busan, but of course history is never wrapped up neatly. Sora and Youngsoo encounter more challenges after being reunited with their family members. After all, the war was still raging, and South Korea was still buckling as a result of the refugee crisis. In addition, Sora still faced the unspoken understanding that Youngsoo’s life was more valuable than her own. In a heartbreaking argument with her mother, Sora lets everything out —- all her frustrations about being born a girl in Korea, and how her life has never been her own.

Lee does not oversimplify either the war or family life. In a scene where American soldiers enter a village, Koreans stand on the side of the street, waving South Korean flags and cheering them on like heroes. The Americans throw Tootsie Rolls, to the great delight of the Korean children, but the soldiers also call them “gooks” under their breath.

History is not pretty, and Lee is not out to make it more palatable. Despite the roadblocks in front of her, Sora will survive and even thrive, but in this author’s interpretation, the way is not easy.