One adoptee’s story | By Mindy Tsonas (Summer 2020 issue)

As a Korean adoptee, I have always known that I was adopted. In fact, my parents had always celebrated this fact by telling my adoption story as our own personal fairy tale complete with happy ending. Strangers would often stare and look confused when I called the woman with the light brown hair and blue eyes “mom.” Growing up in a predominantly white town, I always knew these stares meant something important but I had no idea why.

Though I have always known my family loves me, as a transracial adoptee love and belonging have always felt complicated. I didn’t understand until recently how deeply race was a part of that complexity. Despite what my parents told me, that they would love me if I were any color or stripe and what I looked like didn’t matter, this would eventually become problematic. As a child, I had no reason to believe otherwise and no context to identify or understand the micro-aggressions and racism I was already experiencing. My parents were the center of my universe, so I simply believed what they believed without question.

As a teenager, I worked hard to be the model daughter. This is a common experience among adoptees – this struggle of feeling like we have to prove our worth, to show our gratitude by being good so our parents would not regret adopting us. This often means erasing our Korean identity. I got good grades, I had lots of friends, I was a cheerleader and gymnast and had a boyfriend. I hid my internal struggles as we are taught to do. All the while the narrative of colorblindness, how I was told by my family that my race didn’t matter, was constantly in conflict in a world that always saw my race, and it mattered in ways I was not prepared for. I struggled through most of my early adulthood trying to reconcile a Korean identity that was completely whitewashed.

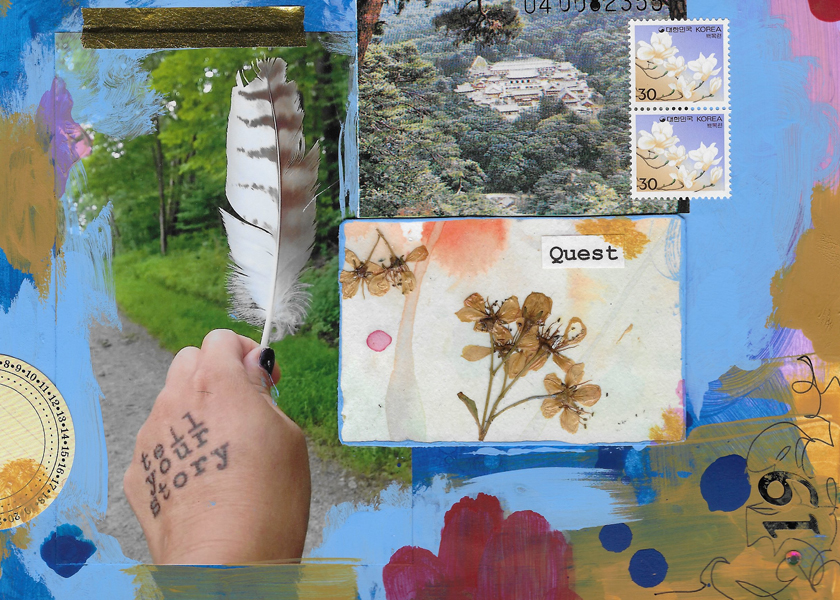

My creativity is what ended up carving a path forward for me. It was a way for me to process my emotions, ask hard questions and begin to reclaim different aspects of myself, piece by piece. Inside the messy metaphor of painting and writing it all out, sharing my truth through my art helped me discover who I actually was beneath all the complex familial, social and cultural narratives. A big part of that truth was finally acknowledging that my race does, in fact, matter.

Divesting myself from internalized whiteness (the constructs of oppression, not the color of people’s skin) and reintegrating my Korean identity has been complicated process. Though oftentimes confusing, it has ultimately been liberating and empowering. This will continue to be a lifelong lesson: Unlearning all the ways I thought I must conform to a dominant narrative in order to be loved and to fit in.

I don’t know if my parents and I will ever be able to talk in depth about race. I understand the many reasons why they have not been able to, and I do have compassion for their individual history and journey. But I’m also clear that having to face racism alone since I was a young child felt like another kind of abandonment. Coming to terms with this part of my experience and accepting our differing worldviews is now part of my own healing journey.

In this cultural moment where we are all facing a global health crisis and a racial pandemic, my Asian identity directly confronts all of my relationships, especially my belonging within my own white and biracial family. It also deeply challenges how I might continue to fully belong to myself. This I have learned is the most important truth of all —- as an adoptee I must never again be willing to abandon any part of myself.