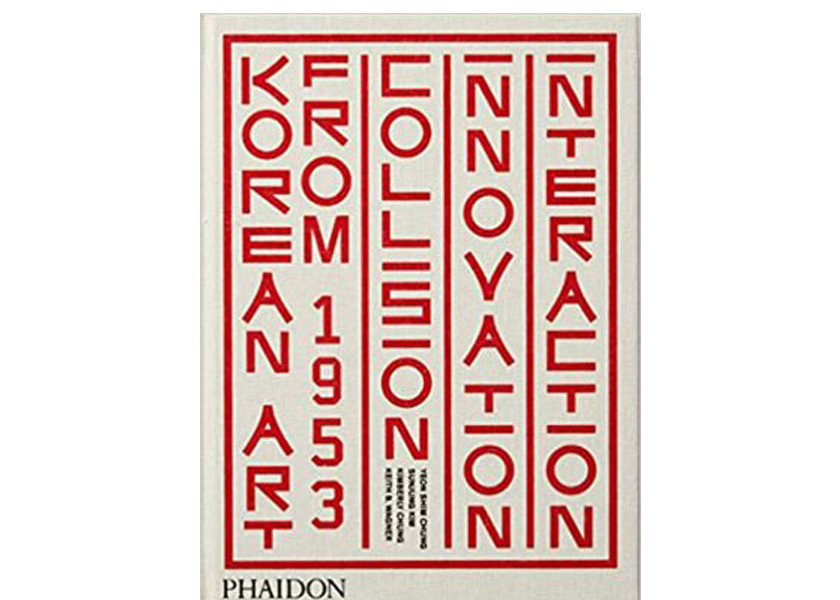

Korean Art from 1953: Collision, Innovation, Interaction ~ Yeon Shim Chung, Sunjung Kim, Kimberly Chung and Keith B. Wagner, eds.

(Phaidon Press, London, 2020, ISBN #978-0-7148-7833)

Review by Bill Drucker (Spring 2020 issue)

In Western countries, the best-known modern artist is the iconic South Korean avant-garde artist, Nam June Paik (1932-2006). Called the “father of video art,” Paik incorporated video, music, and experimental performances into his visual art. He came into the modern art scene just as both the U.S. and South Korea were transitioning socially, politically, and technologically.

Paik is just one recognized name among many Korean modernist artists, many of whom are described and their work shown in this new book. Korean Art from 1953 looks in depth at the Korean modernist movements that propelled art outside its traditional frame. In Korea, modern art and history are intertwined in a complex social, psychological, and cultural dynamic. The generation that came before 1953 was influenced by colonial rule, wars, and national division. The generation after 1953 confronted western ideologies, capitalism and the emerging digital technology.

Modern art is never “art for art sake” in South Korea, but responses to questions of the identity of self, society, politics, and local and global happenings. In communist North Korea, art is the single-minded didactic extension of the state communist ideology.

Contributors to this work narrate the influences that characterize the period of modern art history. The book relates this story in two sections corresponding to the time periods from 1953 to 1987, and from 1988 to the present.

1953 was a milestone date for Koreans; the year the war finally ended, and Korea’s modern era began. Shifting social and political realities heavily influenced modern art. There was a theme of Korean identity or “Koreanness” by artists Sooneun Park, Ungno Lee, Jung-soeb Lee, Whanki Kim, Youngkuk Yoo and others. They struggled to create a Korean aesthetic at a time when South Korea was still struggling to throw off vestiges of colonial rule and was overrun by western influences. Native artists knew Western modern art trends; they were familiar with Cubism, Fauvism, Art Informel, and Abstract Expressionism.

Early works such as the lush One Autumn Day (oil on canvas, 1934) by In-sung Lee shows the influence of French art on Korean modern artists. The bold colors and depiction of a bare-breasted woman looking directly at the viewer is reminiscent of the work Paul Gaughan did in Tahiti. Even in the 1930s, there was a modernist aesthetic in Korea.

The Korean modern art communities, in part as protest against the dictatorial rule and in part as new, liberated expressionists, was divided into several main camps: The Origin group; Shinjeon; the Zero Group, the Fourth Group, the Avante-Garde (AG); and the Space and Time group (ST ). Their means of artistic, social and political expressions included new elements of performance, experimentation, and use of materials. In performance art, actors and art were set in motion, with themes of identity, social protest, and historical events.

The 1974 German publication The Theory of Avant-Garde by theorist Peter Burger and other writings had great influence on the Korean modern art scene. The new vocabulary of “deconstruction” and “destabilization” liberated artists from the established artistic constraints and cultural borders. The older aesthetics and traditional art movements gave way to the new rules of artistic engagement.

One notable Korean modern art movement was dansaekhwa or “painted in a single color.” These works, usually in a light monotone or neutral colors, maintained an Asian minimalist character and style. The Japanese were well-known for their contributions to this style. These works had a surprising sense of movement, and were progressive in style. The leading artists included Chong-hyun Ha, Hyong-keun Yun, Sang-hwa Chung, and Ufan Le.

As the country grew more stable, and prospered economically during the the ‘70s and ‘80s, there was increased friction between the rigid state regime and progressive artists, and a constant state of political and social agitation in the greater society.

There were other voices of protest in society as well, including from social activists, college students, the intellectuals, factory workers and farmers. From rapid modernization in South Korea emerged repressed social unrest. Minjung (the people’s movement) was expressed in art, photography and other media. The 1980 Gwangju Uprising was a galvanizing milestone in the people’s movement.

Artists produced works in themes of social realism, often starkly produced with bold, violent colors. Favored media styles included painting, photography, video and performance art. During this time period, artists also created counter-realism art. Joung-ki Min’s Longing (oil on canvas, 1980) shows a tranquil, rural scene, in a European style. His painting Embrace (1981) of two lovers kissing intimately is a distinctive and haunting work.

The social realism movement advanced photography as a powerful medium. Images of poverty, people getting arrested, and protesters colliding with the police immediately impacted the audience.

North Korean social realism carried its own messages to the public. Based on Russian propaganda and (North Korea’s second leader) Jong Il Kim’s Art Theory (1992), state sanctioned art and photography advanced the nation’s communist and socialist ideologies, and the importance of loyalty to the state. Despite its limitations, this art work is characterized by high-quality aesthetics.

In the post-1988 era, South Korea wanted to show the world its “coming out” as a stable, prosperous, modern nation, beginning with the Seoul Summer Olympics. As artists, writers, students and grass roots movements showed, however, the intended national image was a thin veneer. Under the surface, a repressive regime tried to keep the lid on the growing demand for civilian administration and democratic policies.

As the nation settled into a new, democratic period post-1988, South Korea’s modern artists were less affected by wars, division, and poverty. Instead, they looked at new conflicts of individual and social identity. Western influences including TV and pop culture, status-seeking behavior and conspicuous consumption, and even fast food.

South Korea’s liberal overseas travel policies beginning in 1987 allowed Koreans to see the world outside the national borders. Artists and students studied abroad in greater numbers, and knowledge of art trends in other places also increased. South Korean modern art adapted to and reflected global themes.

Globalization opens up new cultures and values, but it can invade a native culture like a virus. Korean artists joined international events such as biennale (bi-annual) art exhibitions in foreign countries. In addition to showcasing Korean aesthetics, and to make Korean art more cross-cultural; uniquely local as well as universal.

Another developing theme of the modern era, was gender, specifically Korean women’s identity. Women artists wanted to express the social, political, sexual and biological constraints they experienced. Artist and photographer Jia Chang and her naked self-images, including Peeing Standing Up, suggest themes of feminine liberation.

The emerging work defied traditional Confucian values that treated women as second-class citizens. Women’s activism began in the ‘90s, although a brand of women’s advocacy began in the ‘80s with a social movement that included enrolling in university, delaying marriages, and embarking on careers. The later movement of women beginning in the ‘90s was characterized by the freedom to choose status, social roles, marriage and childbearing.

Other post-modern movements examined the interaction of abstraction with reality. The vanguard artists included Bul Lee, Jeong-hwa Choi, and Yiso Bahe. The influence of Buddhist thought and Korean Seon (Zen) can be seen in abstract works emphasizing minimalism and spaciality.

Overseas Korean artists in France and the U.S. examined new themes of immigration, bi-culturalism, identity and citizenship. The artist Yiso Bahe’s Fast After Thanksgiving Day (1984) shows the artist walking across the Brooklyn Bridge, dragging a metal rice pot behind him. The solitary walk across the iconic bridge suggests the alien, and un-American. The rice pot suggests the vestiges of the old tradition. Crossing the bridge is a metaphor for transition. Other messages in protest of western capitalism, such as fasting as resistance to the American tradition, are contained in this work.

This big, beautifully produced book on modern South Korean art is profusely illustrated, and includes informative essays by experts. Whether one loves it or hates it, modern art, labeled as avant-garde, abstract, experimental, sociopolitical expressions, serves to reflect and inform our understanding of modern Korean history and culture.

Korean Quarterly is dedicated to producing quality non-profit independent journalism rooted in the Korean American community. Please support us by subscribing, donating, or making a purchase through our store.