Two souls barely survive the inhumane world of public school | Film Review by Bo Brown (Spring 2020 issue)

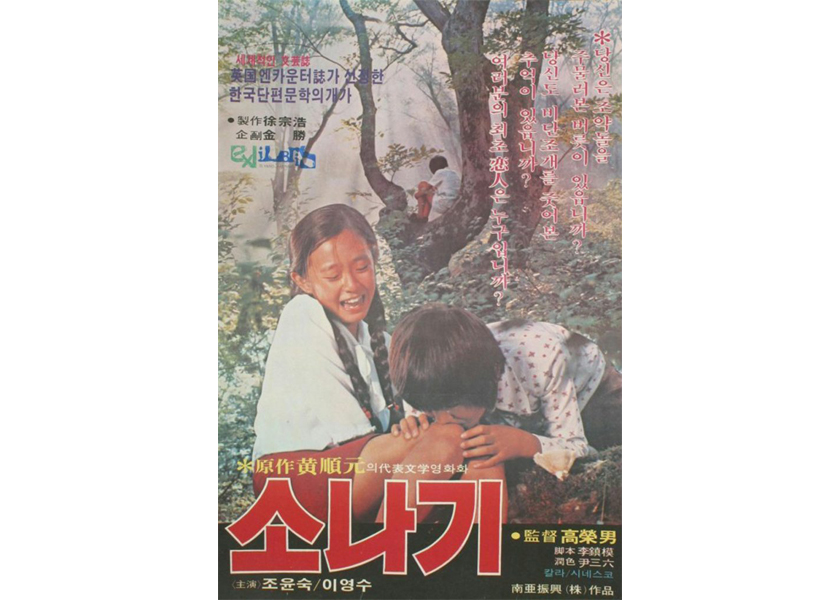

The Shower (Sonagi), (1979), Directed by Yeong-nam Go, Screenwriting by Jin-mo Lee, available on YouTube

The period between childhood and adulthood can be both confusing and exciting. It is a time of feelings but not necessarily of understanding. At its heart, Sonagi (The Shower) is the story of two souls, both barely into their preteens, going through an inevitable transformation.

The film opens with quite a long visual celebration of the innocence and beauty of country life. A young boy, Seok (played by Yeong-su Lee) sits in trees, rambles about and annoys the local flora, fauna and livestock. A train passes. On that train rides a girl Yuni (played by Yun-suk Jo) brought home by her disgraced father. Seok first sees her as he walks home from his countryside ramble, and since he is still at the beginning of their life journey, he is suitably unimpressed.

Soon we see that Yuni tries to make friends with other children at school but is constantly rejected. Her family are the local community leaders, but they have fallen from their perch. And she is a city girl, friendly and open, not like the other children who stick tightly to their own cliques. She doesn’t follow their procedures and she does not recognize her own lowly social position in her new school.

Her relationship with Seok has a rocky start, but one day they decide to take off and visit the nearby mountainside (despite Seok’s obligation to help out at home). This is where the film’s title comes in. A sonagi is a sudden, vigorous summer rainstorm. The children are caught in one and have to wait it out. Their relationship blooms, but, like many so many stories of young love, it also hints at a slide into tragedy.

The film is based on a short story of the same title by Sun-won Hwang. About eight pages long, Hwang’s story skillfully conceives a captivating interlude. A film based on a novel, for instance, has to hit all high points in the source material while necessarily dropping much of the detail. The creators of a film based on a short story have the opposite task: To take a collection of high points and flesh out a full world (much as readers do in their imaginations while reading a short story). This film uses a number of tools to expand upon the world suggested in the short story,

The first tool is the physical world itself. As noted, the film opens with a long visual essay on the simple joys and virtues of country life. It uses the colors and atmosphere in the boy’s environment to focus our attention on the birds, insects and flowers in a vivid landscape. Seok is portrayed as an innocent completely immersed in this loveliness. At the end of his trek, before we meet Yuni, we see the first of many visions or dreams.

These dreams are used to bulk up the film. Seok fantasizes a small, fairylike woman who appears in a leaf bikini top and skirt, perhaps meant to establish his nascent sexuality. Later, Yuni’s grandmother tells her a story of a gumiho (a fox spirit who appears as a beautiful woman to literally steal men’s souls), and the girl has a fevered dream about the creature. The penultimate scenes in the story are a dream experienced by Seok where Yuni (who is ill in real life) appears as her vibrant self, with smooth braids and dressed in fine traditional clothing (hanbok), and they attend the annual harvest festival (Chuseok). Their last imaginary journey is a poignant one.

Hwang (1915-2000) wrote Sonagi while a he was a refugee during the Korean War. This writer’s body of work is considered part of South Korea’s literary canon, and this short story is one of the more famous of the collection. As originally written, it is a timeless evocation of young love.

The film handles the passage of time in a dreamlike, back-and-forth manner. We definitely feel we are in the 1970s, when the movie was made, but never quite know how many days or nights have passed. This treatment serves the story well. It seems like the entire incident is almost a fevered dream for the boy, peopled by an imaginary girl, with real family and neighbors filtering into view and then fading, until the inevitable point where he must awaken and come back to his real life.

The movie is nostalgic about the past of one’s childhood. In a Korean context, that past also means the days before the mad rush to industrialization when life was simple. Starting in the 1960s and into the late 1970s, the Korean government modernized by various drastic methods. The countryside was disappearing;, the old ways were being left behind.

This movie has an air of a wistful look back, more nostalgia than history, more fable than memory. The older country folk are dressed in traditional white hanbok. Seok’s mother is a laundress, and her own clothing as well as that of her husband, a farmer, shimmers and shows its fold lines even at the end of a grueling day in the fields. Despite stains or tears, the intense, routine care she puts into her work is evident, whether boiling or rinsing cloth, or beating it with sticks (a traditional pressing method).

Yuni’s great-grandfather, the local great man, still wears this hanbok, as does his wife. The film takes what happens in the short story to this family and runs with it. Yuni’s father, a failed businessman who has lost all the family’s wealth, slinks about uselessly in a dark western business suit. He is said to be drinking away his sorrows in the local pub while his grandmother tends his sick child. Yuni’s great-grandparents provide her a home, but their loving care is not enough to save her from her father’s fiscal ineptitude.

In contrast to their elders, the schoolchildren wear modern clothing, and the costuming reflects the loud, artificial colors of 1970s fashions. At the start, the boy dresses sensibly for hot weather and country life in shorts and white short-sleeve shirts. But when he decides the girl is worth pursuing, he gets out his good clothing —- a print Quiana shirt and brown bell-bottoms —- and never takes them off again, to the horror of his laundress mother (Seok’s interactions with his mother provide a nice dose of levity). Yuni’s dresses seem more expensive than the other kids’ and more fashionable as well. Eventually, her clothing also comes to have a symbolic meaning.

Many of these tools find their roots in the original short story, but there they are applied with a much finer brush. The story is rooted firmly in real life; there are no fantasy sequences. Only one person’s clothing choices are important. The sonagi rushes over the children and they deal with its consequences, but the countryside is evoked rather than smacked into our faces. The children’s school is mentioned, but only in passing.

The children’s school feels like a convenient metaphor for the cruel, unfeeling world. The children there are unsympathetic and brutal. Rather than real people, they feel like props with set characteristics meant to evoke certain emotions and trigger plot points. Over 20 actors are credited, but when it is over, one only really remembers four —- Seok, Yuni and Seok’s parents (and to a lesser degree, Yuni’s grandparents). With the exception of dream sequences, where they play a bigger role, we hardly see adults all. In addition to the families, there are a few farmers chasing kids away from their crops and tending a small number of cattle. For a farming community, there are not many farmers hanging about.

But the work the actors do, with the script they are given, is excellent. Unlike that old Hollywood trope about ruining a scene by featuring a child, the two stars carry the action well. Life is presented from Seok’s point of view. Except for some added scenes between Yuni and her family, we are completely immersed in the boy’s world, his reactions to the girl, and his memories of her and her family. Yeong-su Lee as Seok presents an excellent physical portrayal, and his face is an ever-changing canvas of emotion. Whether he is angry, baffled, happy or lonely, it is reflected in his face and even his physical posture.

Yun-suk Jo as Yuni gives a charming performance, in which interactions with characters other than Seok paradoxically present a better picture of her inner life. She is curious about the other children, and when they reject her, we see just how she is built. With Seok, however, she mostly just laughs. She clearly flirts with him, and his reaction is one of anger and bafflement. But this is how the boy views her; it makes it feel more like his world rather than hers. The two actors play well together.

The sensibilities of the movie fit squarely in Korea as portrayed in popular media, particularly since the phenomenon of hallyu, where Korean culture is presented via popular media such as TV dramas and films. These emphasize concepts such as the importance of family, the idea of shared shame and the romance of country life. This is most evident in the interactions between the children. They fall in love, but it is an innocent love. They don’t paw all over each other; there is not even a sweet first kiss.

In this movie, one can see the roots of the endless romantic dramas that have made up the bulk of hallyu offerings over the years, with their unrequited first loves, poor boy versus rich girl (or vice versa) sensibilities, wordless longing, and as a more specific instance, the rain scene.

In this trope, two people are caught in a sudden weather incident where they must shelter together in circumstances normally found heinous by Koreans. They first draw away from each other but are forced by circumstance to shelter extremely close. This allows the parties to express their feelings because they have no choice in the matter, which is far more acceptable than expressing them on one’s own. It has become a common device in modern Korean film and television storytelling.

The movie is considered a classic. In 2017, an animated version of the short story was released. Romantic comedies routinely reference the story; a well-known parody appears in a scene in My Sassy Girl. So the movie that looked back on past days with tinted glasses is now itself remembered with nostalgia and affection. Not a bad rounding of events.

Korean Quarterly is dedicated to producing quality non-profit independent journalism rooted in the Korean American community. Please support us by subscribing, donating, or making a purchase through our store.