Two views | Reviews by Jun Young Chung and Grace Ji-sun kim (Spring 2020 issue)

Parasite, Directed by Joon Ho Bong, DJ Entertainment

Review by Jun Young Chung

Different. When I left the theater, I inhaled. I felt different, like I had just gone through 132 minutes of looking at a Picasso for the first time. It was that shocking to me. Even for me, a person who has been watching Korean films for more than a decade, Parasite was more than just a movie. It was direct, but did not step out of line. The film was a hard truth to swallow, but entertaining and enjoyable at the same time.

Parasite has gained remarkable recognition around the world. It has grossed $53.4 million in North America and total of $266.9 million worldwide. It sets a new record for the director, Joon Ho Bong, as his first film to gross over $100 million worldwide. The notable accolades received by Parasite include the Palme d’Or at the 2019 Cannes Film Festival and the Best Director, Original Screenplay and International Feature Film at the Academy Awards. For his originality and effort, Bong was also awarded the coveted Best Picture prize, the first South Korean filmmaker to earn that honor.

Following its Academy Awards success, Parasite also received significant rescreening. The Associated Press reported this as the biggest “Oscar effect” since 2001 after Gladiator won the Oscar for Best Picture. The box office revenue increased by more than 230 percent compared to the week prior to the Academy Awards.

Parasite is not just about conflict between the poor and the rich. The genre of the movie is fluid. Moving from social criticism to thriller to action, Parasite defies characterization. Bong’s previous work is reflected in this movie. He weaves bits of his former movies, like Memories of Murder, The Host and Snowpiercer, into the themes and style of Parasite. Bong has poured all his experience and creativity into this movie, which he has said is influenced by the work of Stephen Spielberg, Alfred Hitchcock, and Ki-young Kim, creator of the tense social-class crisis film The Housemaid, as well as Chang-dong Lee who created the psychological thriller Burning.

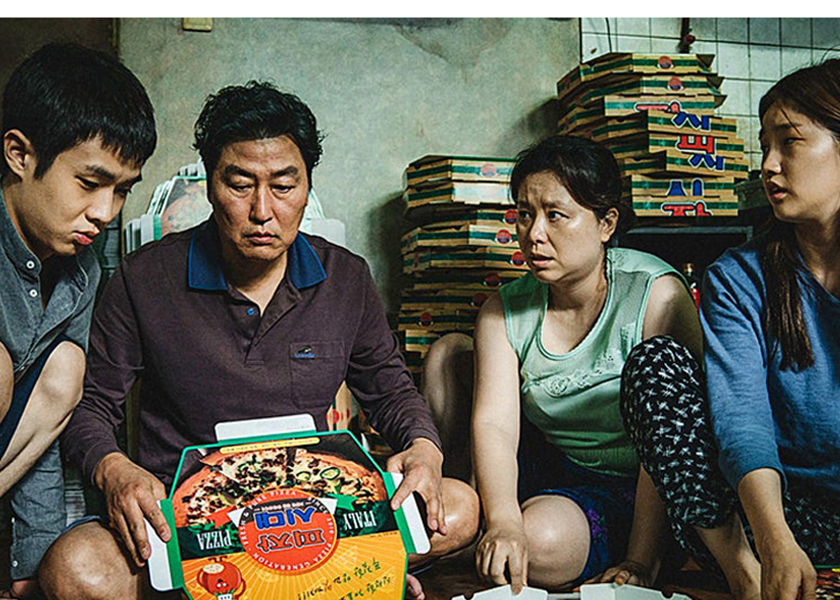

Parasite begins with Ki-taek Kim’s (Gang-ho Song) family, who have accepted and become accustomed to their poverty-stricken lives. Everything they do smells of poverty: They have to climb to their toilet (which is elevated, because they live in a basement) to freeload off their neighbor’s wi-fi, and the whole family has to do piece work, assembling pizza boxes to earn money. A description of the family and their lifestyle sets up the story to show the stark contrast between them and the wealthy Parks, who are introduced later.

When the benefit of an education credential (a fake one) offers the Kims a chance to elevate their lifestyle through subterfuge, they don’t hesitate. They forge certificates and lie to the rich family with no regret or remorse. With the help of their newly-minted educational credentials, Ki-taek’s family infiltrates the family of Dong-ik (Sun-kyun Lee). In a society where education is the price of admission to the social ladder, this plot provides a perfect analogy of modern Korean society.

At first, all seems to go well for Ki-taek’s family. They successfully infiltrate the rich Parks’ house under false colors as a well-to-do family. However, Ki-taek and his family soon realize they cannot be one of the rich. Tension builds as Bong provides details to hint that something is about to go very wrong. Bong uses this tension very effectively to play with the audience. He takes us down a road with many twists and turns.

A severe rainstorm forces Ki-taek and his family, who have been “parasiting” in Dong-ik’s house, to scramble into hiding just as Dong-ik’s family unexpectedly returns early from a camping trip. From here, the real conflicts start as Ki-taek’s family uncovers the secret life of Moon-gwang (Jung-eun Lee), the ex-housekeeper. The movie quickly turns into what nobody would have expected from the opening scene. Here, I’ll save my words to prevent any spoilers.

Parasite is a masterpiece. Bong knows exactly what he wants out of each scene. He works with cinematographer Kyung-pyo Hong (Snowpiercer), who has also collaborated with Bong on several other films. Impeccable camera work perfects the tone and mood of Parasite. Using techniques such as framing, lighting and controlling the set, Bong provides the viewer a sense of satisfaction —- one of many emotions one experiences while watching this film.

Inspired by Kurowasa’s High and Low, Bong initially uses a camera angle shooting down on Ki-taek’s family. After the Kims infiltrate the rich family’s house, we look up at them. Ki-Taek’s family is shot in a small window whereas Dong-Ik’s family is shot with a more expansive, wide view. The lighting used by the cinematographer, Kyung-yo Hong, also helps Bong naturally address the issue. The banjiha, or “half underground” house where the Kims live, lacks natural light. On the other hand, the Parks’ house is filled with natural sunlight. With these techniques, Bong, also makes a subtle commentary about social class and other issues.

The rhythm and pace of the story change constantly, always adding more tension and stress, which ultimately provides catharsis when it is all resolved. Music by Jae-il Jung, whose work Bong has used in his previous film, Okja, contributes to a jittery atmosphere with what Rosie Pentraeth in a piece in Discover Music calls “minimalist piano pieces, punctuated with light percussion.”

The way Parasite critiques South Korean society makes the film easy to relate to for people around the world. Inequality and poverty are seldom discussed with real candor. It’s not a topic many people find amusing or entertaining. Considering that a large percentage of the cinema audience is not poverty-stricken, it might even be a topic many want to avoid. However, Bong tackles these issues without hesitation. No doubt about it, Parasite will be talked about for a very long time.

The burden of climate change in Bong Joon Ho’s Oscar-winning film

Review by Grace Ji-Sun Kim

The South Korean film Parasite has won four Oscars, including the first-ever best picture award won by a subtitled film. Seeing an Asian film dominate the U.S awards season might represent some progress in representation, or it might just represent the monumental achievement of filmmaker Joon Ho Bong. Either way, Parasite’s big night was a moment of collective pride and joy for Asian film lovers everywhere.

The film offers a witty story about a poor family and a rich one. The Kims live in a cramped semi-basement apartment in the dark depths of Seoul, while the Parks live in a sleek, architecturally-astounding home atop a private hill in the affluent neighborhood of Gangnam. Parasite comments on South Korea’s growing economic inequality and social divide.

There is also a secondary theme: Climate change, and specifically its disproportionate affects on the poor. Joon Ho Bong makes sharp observations about climate change, and the film uses literal barriers and levels to represent its inequitable effects. All this culminates in a rainstorm flood scene. The heavy storm leads the Parks to end a camping trip prematurely and then relish the beautiful sunny weather that follows the next day. The Kims, however, find their home and community ravaged by the flood of rainfall, sewage and waste. They have to sleep in an auditorium with other displaced people.

The rainwater sweeps down on the city, thrashing downstairs and basement homes at the lower levels of the city where cheaper homes are situated. This symbol of climate change —- wreaking havoc on the city’s less fortunate, who are quite literally located lower than the affluent —- is given further nuance through the introduction of even poorer people, located even lower than the audience imagined. Where one night of climate devastation takes the Kims’ home and livelihoods, the Parks watch the rainfall from their scenic backyard view and throw a themed outdoor birthday party the next day.

Class criticism is a common theme in film. But this genre-bending, plot-twisting movie says something more unusual: There is no moral dignity for the poor, and there is no corruptive armor for the wealthy. They all have the same flaws and complexities of character. Nor is there a clear answer as to how our world and our people will react to the climate crisis. We want to believe ourselves to be fair and just, but the important question is not how we perceive ourselves or how we perceive the rich and the poor. It is how we will act when the flood ultimately comes down on us.

Reactions to the climate crisis can largely be summed up as follows: A lack of action by those in power, and protest and engagement by our youngest generation. Young people’s efforts to make change are modeling a higher purpose, living meaningful lives through the action taken today for others tomorrow.

Parasite reminds us of the horrifying, perilous weight of today’s reality. We do not find refuge or comfortable solutions, but rather the palpable actuality of consequences to come. The voices of artists, writers and thinkers can help inspire and agitate us to take action in our existential plight. The film’s deeply meaningful message about the devastation of climate change makes me even prouder to be a Korean —- and excited that the film took the biggest Oscar prize home.

Korean Quarterly is dedicated to producing quality non-profit independent journalism rooted in the Korean American community. Please support us by subscribing, donating, or making a purchase through our store.