Mlima’s Tale uses playful humor to explore a moral and environmental topic | Review by Anne Holzman (Winter 2023)

Mlima’s Tale Script by Lynn Nottage

(Directed by Ansa Akyea, Open Book (Minneapolis) and other community venues, February 9 through March 12, 2023)

International ivory bans notwithstanding, the loss of elephants to the ivory trade continues, and it’s no laughing matter. A production of Mlima’s Tale, from the Twin Cities-based Ten Thousand Things theater company, draws belly laughs at human hypocrisy which is part of this remote conservation issue. The actors are hilarious; the story pulls at the heartstrings. It’s an evening’s entertainment that sends its consumers out into a world that needs changing. The phrase “if you’re listening” opens and closes the story, calling on the audience to hear and perhaps to act before more tusks are lost.

Before the actors took the stage on a February evening at Open Book in Minneapolis, Ten Thousand Things’ artistic director Marcela Lorca welcomed the audience back to the company’s first full-fledged production since the pandemic closed theaters. “We hope that this awakens conversations about our relations with the natural world,” Lorca said. And then she added, “Laugh out loud. Talk back to the actors if you feel like it. Have a good time.”

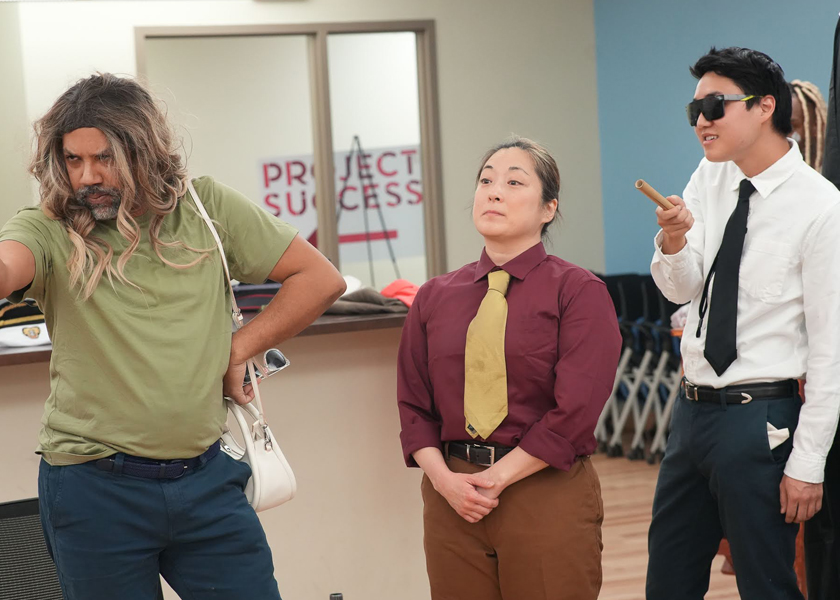

Ten Thousand Things designs all of its productions to be portable. The company travels to schools, community centers, parks, and prisons with a vanload of props, ready to set up in whatever rooms happen to be available. Their challenge is to do more with less, and they target their productions to audiences who might be seeing their first play. The actors develop their characters by means of gesture, posture and voice with minimal reliance on costumes or props. Anything that cannot be depicted through a few yards of fabric, or a stool and a board, has to be delivered through good acting.

In Mlima’s Tale, expert direction is provided by Ansa Akyea. Much depends on carefully-developed accents as the actors’ roles switch rapidly among social classes and continents. Kudos to the company for investing in that effort, with guidance from dialect coaches Patrick Chew, Anh-Thu Pham, and Wariboko Semenitari. The steady hand of Dameun Strange on sound effects also does much to create illusions of time and place.

In this script, written by Pulitzer laureate Lynn Nottage, five actors play many characters, four of them switching quickly from scene to scene, announcing each new location as they also change roles. Brian Bose enacts the painful death of the iconic elephant Mlima in an African nature reserve. He becomes Mlima’s ghost listening to human discussions of his fate, then Mlima’s tusks being shipped clandestinely from Kenya to Vietnam, then to China, and finally an ivory sculpture in the home of an American celebrity, before he joins the circle of storytellers to close the play.

The other four actors, Joy Dolo, Will Sturdivant, Katie Bradley and Clay Man Soo, cover half a dozen characters each. There is no protagonist, really, just a victim of corruption being carried along by series of transactions, variations on a theme that resolves itself with the appearance of an avatar of wealth and power from yet another continent, who ultimately carries the blame for the corruption.

The story opens with elephants singing together (beautifully!) and tossing out names, family lines and brief biographies. These elephants claim the dignity of individual souls. The refrain of names will ring out again as the tusks make their passage across oceans, and the play will end with a reprise, framing the story of losses for elephants expressed in human terms. It is an ambitious premise, and some of the fun of this production lies in our conspiracy as audience and actors believing there are elephants on the stage.

In the play’s early scenes, the motivations that drive illegal ivory exports are carefully explored. The hunters debate honor, compassion, and the need to feed their families. The officials who turn a blind eye – for a price – cite wealth and power beyond their borders.

Motivations on the Asian end of the trade are less developed and the characters less sympathetic. The lack of balance between the ethnic groups and nations opens the script to the danger of stereotyping the Asian characters, which is mitigated by mixed-race casting, but caused me some discomfort nonetheless.

The story holds together, much as some of Shakespeare’s shakier plots hold together, on the strength of compelling language. Nottage has a musical ear and uses repeated lines and images to great effect. There is lyricism in the appreciation of fine ivory sculptures with their ancient heritage. A hunter explains his choices in terms of Islamic morals. An American ship captain (Stars and Stripes propped on a stool, Georgia accent) tries heroically to resist temptation. A model container ship, roughly carved and painted, tosses about Mlima’s body to represent the tusk’s journey across the Indian Ocean while also evoking historic passages of enslaved people. The evocation of elephants’ names and lineages returns here in a haunting chant. The ship docks in Vietnam, and the humans reappear, bringing their corruption with them.

There is a Brechtian self-consciousness about all of this as the actors, mainly staying in character (an actor did lose it in laughter at least once in the performance I saw), appeal to members of the audience for sympathy or agreement. Much of this appears to be improvised, using gestures and vocalizations without straying from the script, and the cast carries it off with great panache.

Leading the charge is Joy Dolo, who plays several of the bullying officials with chilling enthusiasm and appears at the end of the story as the wealthy celebrity who bought the carved tusks. Her forays into the audience drew repeated laughter on the night I attended, including one episode in which she waded abstractedly between rows, clambering over the knees of audience members while shouting into a cell phone.

The best thing about the play is that it really is a “play” – the actors play with one another and with members of the audience, and it’s just plain fun. The aperture between elephants and people widens as human actors attempt to portray another species, with minimal props and costumes, inhabiting them as named characters and endowing them with histories and afterlives. Waves of sadness and joy, humor and regret, rise and fall but leave the central problem unresolved, with work to be done and many directions to explore before we figure out how to put a stop to the cruelty we inflict on another species.

Mlima’s Tale runs until March 12, to order tickets, visit: https://tenthousandthings.easy-ware-ticketing.com/events