Stop Kiss describes a romance in a skillful story with layered meanings | By Joanne Rhim Lee (Summer 2025)

The title of Diana Son’s play Stop Kiss might seem a bit off-putting at first, sounding like a punk band or the cheeky ending of a haiku. But after viewing Theater Mu’s powerful production at the Gremlin Theater in St. Paul, it is clear that this seemingly enigmatic title is just like the play – rich with layered meanings.

In the breezy opening scene, Callie, a traffic reporter in her late 20s who lives in a spacious rent-controlled apartment in New York City, is fretting about how she agreed to meet Sara, a friend of a friend who just moved to the city from St. Louis. Sara recently received a fellowship to teach third grade at a public school in the Bronx, but her new apartment doesn’t allow cats, so Callie has agreed to keep her beloved Caesar temporarily.

Callie was planning a quick meeting and pet drop-off, as she has dinner plans with her on-and-off-again boyfriend George. However, the two women quickly move past the obligatory small talk and seem to forge an instant heartfelt connection, something they recognize as rare among strangers in such a big city. Callie cancels plans with George and opens a bottle of wine with her new friend instead. Over the next few weeks, Callie invites Sara to explore the city with her, and they both begin to see things in a new light.

Sara’s character could be a cliché as the wide-eyed idealistic Midwesterner who arrives in the big city with a desire to help underprivileged children, but Kelsey Angel Baehrens imbues her with such warmth and honesty that the character of Sara feels entirely genuine, like someone we all would want to befriend. Her vulnerability is contagious, and Callie soon begins to open up and peel away the hard shell that she has built up over the years.

As Callie, Emjoy Gavino is also relatable, a woman who used to love to sing and dance and soar, but perhaps has settled for “good enough,” in her job and in her relationship with George. The audience learns her recent past – that she relocated to New York for journalism school more than a decade ago, fell into the comfortable and stable job of traffic reporter, and then lost the impetus to leave.

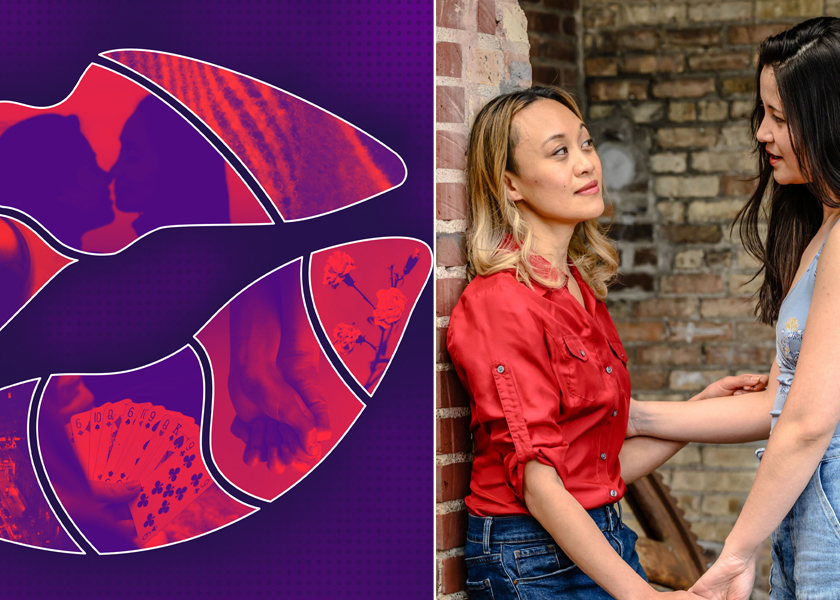

As the two women, who have both only dated men before, become closer, they begin to navigate their growing attraction to each other. They have both fallen for someone they didn’t initially expect to, and we enjoy their endearing playful banter and slowly melting hearts.

This tender, meet-cute romance is suddenly disrupted by a shocking and violent hate crime (not shown on stage). It’s a brutal wake-up call, indicating that not everyone believes that love is love, and feels sadly prescient, more than 25 years after Diana Son wrote this groundbreaking play in 1998. Just like Callie and Sara, the audience surely yearned to see how things would play out in this early-stage romance. Instead, Sara wakes up after having been in a coma, and Callie is injured as well.

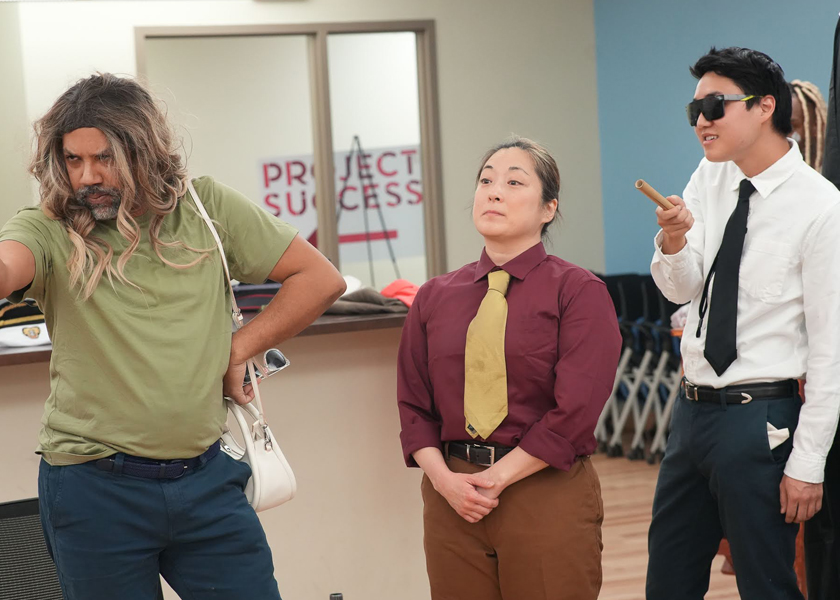

Under Katie Bradley’s assured direction, Stop Kiss unfolds in a non-linear structure, shifting from the budding romance to the aftermath of the attack, in police interviews and hospital rooms. In the hospital scenes, Theater Mu’s production becomes a showcase for the two main actors. Sara cannot speak and can barely move, but Baehrens conveys volumes through her subtle movements and expressive eyes. As the one who escaped the worst, Callie is wracked with guilt, and Gavino captures both her visible grief and the quiet unraveling beneath. Clay Man Soo is stellar as the sweet but sometimes clueless George, and Theater Mu’s former artistic director Lily Tung Crystal also shines in various supporting roles.

The Gremlin Theater is a tiny venue on St. Paul’s border with Minneapolis, with about 100 seats on three sides of the thrust stage, but it’s the perfect stage for this lovely production. Stop Kiss is a triumph – urgent, moving, and not to be missed!

Theater Mu’s Stop Kiss runs until June 29, 2025 at the Gremlin Theater.