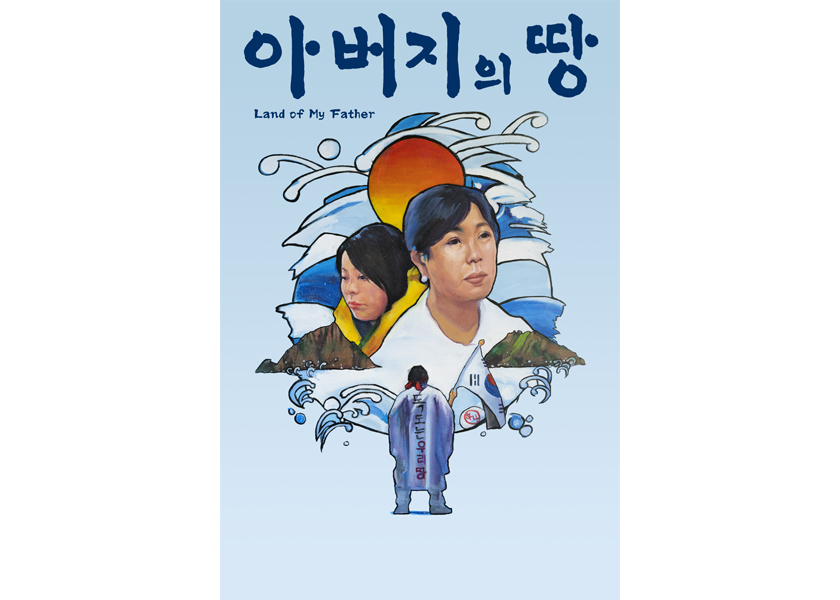

Land of My Father explores national and family love through advocacy for a lonely island | By Joanne Rhim Lee (Summer 2020 issue)

Land of My Father is a new documentary film about Dokdo, two tiny, picturesque islands in the Sea of Japan (East Sea) about halfway between Korea and Japan. Directed by Matthew Koshmrl and edited by Christine Sun Kim, two native Minnesotans, the film was chosen for screening by the Minneapolis-St. Paul International Film Festival in April; that festival pivoted to a virtual format in May due to the restrictions of COVID-19.

Originally recognized as Korean territory, Dokdo was annexed by Japan as part of its colonization of Korea in 1910. With Japan’s defeat at the end of World War II, Korea regained its independence, and assumed that Dokdo was part of this restoration. Japan disagreed, and has continued to view the islands as part of Japan, which the Japanese renamed Takeshima. This territorial dispute has lasted 75 years, and is now being shared with new audiences through Koshmrl’s excellent documentary. (see related feature story on the KQ website)

Who is the father that the title of the film refers to? There are actually two fathers, as Land of My Father centers on two individuals with personal and family connections to Dokdo —- a man whose father survived being conscripted into forced labor by the Japanese before and during World War II, and a Korean woman who grew up on Dokdo with her father. Both of these individuals have dedicated their lives to reclaiming Dokdo as part of Korea, at great personal cost. The films producers (Koshmrl and Kim) have clearly gained their trust in being a part of their documentary, as they share many public and private moments on camera.

Byeon-man Noh, a farmer from Namwon, about three hours south of Seoul, grew up with a father who harbored a deep hatred of Japan. As a child, Noh did not understand the roots of this hatred, but as an adult he learned that his father was forcibly conscripted, in 1939 at age 17, by the Japanese to work in an underground coal mine. He worked day and night in dangerous conditions, and the Japanese even injected experimental drugs into him and others to increase their productivity. At one point, a tunnel collapsed, injuring his foot while he was working in the mine, and it never healed properly. The film shows pictures of young Korean men working in the Japanese mines; they are skeletal, with gaunt eyes and ribs sticking out on their ribcages. Noh reflects on his father’s past, saying, “When I think about what they did to ruin my family and my father’s life, I can’t help but feel angry.”

These days, Noh regularly travels to Tokyo to protest in front of the National Assembly building, hoping to gain the attention of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and other Japanese leaders, as well as passersby. During his solitary protests, he wears a traditional Korean white robe and carries a large white South Korean flag. People on the street watch curiously as Noh shouts at the top of his lungs, “Dokdo belongs to Korea! Takeshima is Korea!”

In interviews, Noh explains that he wants the Japanese government to acknowledge its past, apologize for its 36 years of colonization of Korea, and make changes to Japanese textbooks which list Dokdo as part of Japan. He realizes that these are big asks, but insists that they must be achieved in order for Koreans to live with peace in their hearts. He says it is more than just about the islands, but about Japan’s unacknowledged war crimes during its brutal colonization of Korea, including the kidnapping of thousands of young Korean women to be used as sex slaves for Japanese soldiers.

The other father is Jong-Deok Choi, who was Dokdo’s sole resident for almost 25 years. He made a living harvesting the abundant sea cucumbers and abalone, until he died of a stroke during a huge typhoon in 1987. His wife gave birth to their daughter while they were living on the island, an event that was covered by the Korean news media in the 1970s. In the archived footage that is shared in the film, the young mother cradles her newborn baby and says, “I hope to raise her well, so one day she can help protect Dokdo.”

That baby grew up to be the passionate advocate interviewed in Land of My Father, Kyeong-sook Choi. Though Choi no longer lives on Dokdo, she travels back frequently, organizing tours of the island designed to inform participants about the need to formally recognize it as part of Korea. These tours began in 2005, and are run by the Korean government. Choi admits that while her main frustration is with Japan, she believes that her own country’s government is also to blame by not being more proactive. She says she will continue running the tours until the story of Dokdo is told correctly.

The filmmakers take part in one of Choi’s tours, and the footage looks like a travel agency advertisement for a beautiful, pristine, untouched island —- like a tiny Hawaii but with no inhabitants.

In interviews in her home with her family members, it is clear that some of her children are conflicted about their mother’s work, particularly her young adult daughter. In a moment of striking honestly during a meal, her daughter says, “I don’t think it’s good to be supportive when one continues to fail… If I see you stressed out all the time, as your daughter, should I want you to continue?” As a tear starts to roll, she says that the work is starting to take a toll on her mother, and that she is beginning to resent her for it.

But Choi has been faced with greater obstacles than her daughter’s tears, and explains that she wouldn’t be doing this if she didn’t feel deeply passionate about Dokdo, and hopeful that she can eventually achieve her goal. It’s a tense, private family moment, but demonstrates Choi’s commitment to her cause.

Likewise, Noh sees Dokdo as a higher calling. As he faces aggressive Japanese police and security forces, he says that he is not afraid of any consequences. He hints that he is willing to sacrifice his life for Dokdo, and that his current life is only a bonus life; he already achieved comfort and happiness in his past lives.

The Korean concept of han, which has been described as a sense of grief or longing stemming from personal or national injustice, is clearly at work here. Noh and Choi have a deep longing in their hearts, but rather than being a source of sadness, it is a passionate and admirable longing. Like Dokdo, their han is beautiful, and Land of My Father does an excellent job of portraying both.