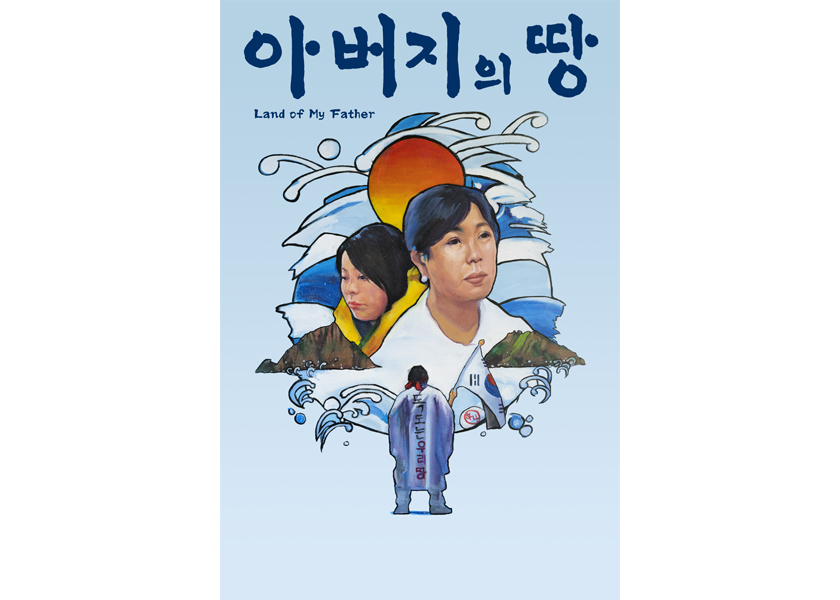

Documentary film Land of My Father explores the symbolism of Dokdo to Koreans today | By Martha Vickery (Summer 2020 issue)

A month after premiering his documentary Land of My Father at the virtual 2020 Minneapolis-St. Paul International Film Festival, Minnesota (see film review) filmmaker Matthew Koshmrl was still waiting to hear whether he could go to South Korea in August or September to see his film at the Jeongju International Film Festival (JIFF). The JIFF selected the film for the festival this spring, but there was no word on whether the films would be shown in a virtual format due to ongoing restrictions necessitated by COVID-19, or if there would be an in-person festival to attend and actual people to meet.

It has been inconvenient, to say the least, to premiere a new independent film in the middle of a pandemic.

Land of My Father is about a very Korean topic —- the controversy between South Korea and Japan over the ownership of a pair of tiny islands called Dokdo, which dates back to Japan’s seizure and occupation of all Korean territory starting in 1910. Japan went on to conquer and occupy many other Pacific Rim countries until it was defeated in World War II. The occupation of Korea and other nations and territories ended with the surrender of Japan in 1945.

Koshmrl and collaborator/editor Christina Sun Kim have shown the Dokdo claim controversy (or Takeshima Islands, as Japan calls them) in a fresh way, highlighting the symbolism of Dokdo as the last Korean territory to still be claimed by Japan, and how this symbol has become central to the lives of South Koreans today. In a larger sense, the film explains the importance of Dokdo as a symbol of Korean autonomy and independence.

Under current restrictions, going to South Korea requires a mandatory two-week quarantine in South Korea upon arrival. Koshmrl is up for it. “It was seven years in the making, so to wait two more weeks to do this is pretty minimal, really,” he said. The Jeonju film festival is “a dream festival” to get into for any film; it is a large, international festival with a wide appeal to the public and the film industry.

At the same time, Koshmrl is forging connections with organizations for screenings outside festivals, including the Korean Association of Minnesota, which expressed interest in having an in-person screening after pandemic restrictions are eased. A Korean Association of the southern states, and the Korean Association of Houston have also expressed interest in a screening and filmmaker talk.

When he is not working on his own films, Koshmrl works as a cinematographer on other people’s films. He spent part of the summer at the U.S./Mexico border filming at some immigrant detention sites as part of a filming crew. These days, he is spending most of his time in his home town of Chisholm, Minnesota, a northern region of the state known as the Iron Range. He is also working part-time on a new film about the history of families like his, the mainly Eastern European immigrants that relocated to the mining towns on the Iron Range in the early 20th century.

Since Land of My Father was paid for through grant money and self-financed, Koshmrl said there is no urgent need to get the film sold as soon as possible. “The point was never to get it out there to make money off it, so I am fine holding and waiting for a good time for people to see it,” he said. Koshmrl has made several short films; Land of My Father is his first feature documentary.

After graduating with a film degree, Koshmrl lived in Daegu, South Korea from 2009 to 2012 to work and to study more about documentary filmmaking. His interest in the topic of the Dokdo Islands initially stemmed from his complete ignorance of the topic, he confessed. He was initiated into the history in a spectacular way when he came across a street demonstration in Korea by Korean War veterans during which ring-neck pheasants, a national bird of Japan, were beheaded onto an old imperial rising sun flag of Japan.

“It was very sensational, and I just didn’t understand it… I had no context for thinking about the Japanese occupation of Korea.” Like many westerners, Koshmrl found the symbolism of the tiny islands difficult to grasp. On the face of it, the dispute about these tiny rocky islands seemed puzzling and trivial. He decided then that if he did a master’s level film degree, Dokdo would be his thesis project.

In 2012, he entered a master’s level program at the University of Texas at Austin, and by 2015, he was ready to do his thesis film. To complete the film, he knew he would need a bilingual film editor. Koshmrl was referred to Christina Sun Kim by a University of Texas professor who had taught her, and had hired her as an editor for one of his own films. After the fact, he learned that she also had a good understanding of conversational Japanese, which was an added bonus in editing the footage shot in Japan.

Kim was also born in Minnesota, but moved with her parents to South Korea at age five, and returned to the U.S. when she was a seventh grader. Although she had a “truly bicultural upbringing,” she also needed to dig deep to understand the pain of the generation that lived through the Japanese occupation. She found she was able to fill in some of the cultural gaps. “That was very important to Matt, to have an editor who had a full understanding of the language and also had a Korean cultural background,” she said. “He saw that that was important right from the very beginning.”

Before starting the film project, Kim said, she had last been in South Korea in 1996. Notably, she did not witness the growth of advocacy by the former comfort women and former forced laborers and the awareness of the Dokdo territorial issue that emerged in South Korea during the ‘90s and early 2000s. “I felt like I was an outsider to Korea as well, when we started the project,” she said.

With a grant from the University of Texas, Koshmrl took a four-person grad student film crew to Daegu for a few months for the initial filming in 2015, and made two shorter return trips in 2016 and 2019.

It was 2016 before Kim started watching the raw footage. When she was finished, Koshmrl had someone to talk to about it. “It was an incredible experience,” Koshmrl recalled. “I suddenly felt like I was out of the silo.”

Not every documentary filmmaker uses a film editor, Kim said, the addition of another person who knows the material can contribute significantly to the project. “Once you have a collaborator you can inject a freshness into your vision,” she said, “and you may end up making a better film that is more faithful to your original idea, in my opinion.”

At first, Koshmrl said he wanted to do a broader film about the Dokdo issue. In the end, Kim and Koshmrl pared 350 hours of footage taken over three years, covering five possible characters. It became a 75-minute film that follows just two Dokdo activists: Kyoung-sook Choi and Byeong-man Noh, who coincidentally, were both inspired to their advocacy for Dokdo by their own fathers’ stories.

The two “painfully” decided to omit a third character from the film, Kim said. The character was a student whose back story as a North Korean refugee was compelling. That left the film with two middle-aged characters whose fathers lived through the war and occupation. Koshmrl wanted a next-generation character, a younger person who also believed in the importance of Dokdo and would carry on the legacy into the future.

They finally settled on Choi’s daughter Hyun-byul. “We thought that Hyun-byul actually is a better representative of someone from the younger generation developing that heart-connection to the place,” Kim said. The connection to Dokdo is more removed for the generation that did not live through the war or occupation, “but in Hyun-byul, we kind of saw that evolution of how the idea becomes a real thing —- we pursued that.” Over the course of a couple years, Hyun-byul grows into a deeper understanding of the significance of her mother’s work. Kim and Koshmrl capture several significant conversations between the two.

The film concentrates on two people, but Dokdo itself is also an enigmatic character. Unique, alone in the East Sea, Dokdo rises out of the ocean, the top of a mountain sticking its highest peak above the surface. Like its geography, Dokdo seems to hide much more than it reveals. Koshmrl and Kim discover that the heart of the story is the significance of that place in other people’s lives, much more than the facts of the dispute between Japan and Korea about the territory itself.

As Choi relates in the film, she had lived with her father as a resident of Dokdo in the ‘60s and ‘70s, when a small fishing village was established there. Since the early ‘90s, there are no residents and the South Korean government maintains the island as a natural preserve. The film follows Choi’s efforts to have her father’s residency on Dokdo officially recognized by South Korea, and to educate about Dokdo history and her father’s place in it.

The film follows Choi’s work as a tour guide to Dokdo, which requires a two-day trip by boat, because it is so far to the east of mainland Korea. Depending on the weather, the boat sometimes cannot risk landing at the Dokdo wharf. When it does, visitors can only stay a half hour.

Byeon-man Noh, a farmer from the southern city of Namwon, was inspired to advocate for South Korea’s Dokdo claim because as an adult he learned that his father had been forced into slave labor by Japan, the fate of an estimated 725,000 Korean young men of that time. He was worked in a coal mine in Japan under inhumane working conditions; included in the film are photos of the painfully-thin Korean laborers who were often worked and starved to death.

Former slave laborers are one of the survivor groups that have advocated for an apology and reparations by Japan. However, Noh seldom demonstrates with any group. Instead, he regularly travels to Japan to demonstrate by himself in front of the Japanese legislature in Tokyo. He wears a traditional white Korean outfit with political messages written on it, shouting in Korean that Dokdo belongs to Korea and brandishing a sign written in Japanese. To Noh, Japan’s claim of Dokdo ownership is as false as its past claim on other Korean territory, and as false as its claim to the bodies of slave laborers and military sexual slaves from Korea.

Japanese embassy in Seoul.

Koshmrl notes that viewers have had a variety of reactions to Noh’s tactics as shown in the film. Particularly American viewers, he said “think he is totally sensational and hurting his cause for being sensational. But others see the police around him, suffocating his protest and feel total empathy for his disenfranchisement,” he said. He has seen friends cry when they see his lonely protest, while others “simply think he’s crazy.”

Koshmrl employs an observational documentary technique known as cinema verité, which typically involves amassing a lot of footage over a long period of time. The filming is done with little or no direction, and the story is put together during the editing process. Kim watched the film footage for a year, part-time and between other projects before she was ready to edit, she said.

Embarking on the editing phase, Koshmrl said “I knew the themes I wanted to explore,” but since the editing process took four years “I had to evolve with the film and the way I thought about Dokdo. …I was really interested in the passing down of this history, how to memorialize the generational trauma, and I was also interested in how to memorialize an atrocity without indoctrinating hate.”

Interviews of people on the streets of both South Korea and Japan are striking in the film because of the contrasts. South Koreans seem informed and have an opinion about the Dokdo claim issue; but in Japan, passers by are vague on the topic. The idea of Dokdo “still affects people’s lives, and it is very much a part of life for the subjects of my film. I don’t think that is true of any Japanese person,” Koshmrl said.

That Japanese people are hazy on aspects of their own country’s history is not unique to Japan, Koshmrl pointed out. “I think we are going through something in the U.S. right now where the majority of the public are not educated on the black experience in the U.S., and what the Civil Rights movement was about,” Koshmrl observed, adding that it has to do with who controls the telling of history.

The Japanese government has notably attempted to control the telling of their history even outside of Japan, such as the incident in which the mayor of Osaka in 2018 condemned the memorial to the former comfort women before its unveiling in San Francisco and cut his city’s “sister city” ties to San Francisco in retaliation, Koshmrl remarked.

The film also includes a short clip of a speech in which the Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe states that the generation of Japanese born after the occupation should not be made to apologize for the actions of their nation before they were born. Abe’s attitude about Japan’s war legacy and its affect on the Korean people continues to be contradictory, Koshmrl said. He has sometimes apologized for war crimes such as military sexual slavery, “but a week later he will say it was all voluntary. …they will admit and then deny in a very confusing way.”

There is also a short clip of a speech by Moo-Hyun Roh, when he was South Korea’s president, in which Roh notes that Dokdo was the first Korean territory to be occupied by Japan. Kim said the occupation of Dokdo preceded the occupation of other Korean territory because it was a military post for Japan during the Russo-Japanese War. That it should be the last place to be ceded formally to Korea makes Dokdo even more important to the war legacy, she said.

The lives of the two activists are shown as uneventful on a day-to-day basis. In one sequence, weather prevents Cho’s tour from taking off to Dokdo from the nearby island of Ulonggdo, and some of the tour participants are impatient with the delay. At one point, there is a mix-up with her permit to stay on Dokdo for more than the allotted 30 minutes. She works hard, but her efforts are often frustrated due to government permits and controls.

Noh is shown in his daily life, patiently trimming trees in his orchard, and going through the repetitive tasks of farming. He travels, uncomfortably and anonymously, to Japan to do his protests. Intermittently, police surround him, forcing him to shout his protest from behind them. He speaks no Japanese, and is frustrated at not being able to communicate with his minders. At one protest in Seoul in front of the Japanese Embassy, he is arrested and bundled into the back of a police car for trying to deliver a written message to the embassy door.

The pace was intentional, Kim said. “Mr. Noh’s and Mrs. Choi’s lives really haven’t changed much. …that is really what it is.” Choi is still fighting with the government over her father’s legacy and her right to live on the island with very few new developments.

Noh’s campaign continues on —- he calls himself an “egg” against the “boulder” which is Japan. He cannot hope to win, he says, only to be destroyed and make the boulder a little dirty in the process.

As observers, Kim said, she and Koshmrl learned a lot about the Korea-Japan dispute over Dokdo, and “we both sort of concluded that this fight is ongoing and will never end. Between the two countries, Korea has their own narrative about the war and occupation; Japan has its own narrative. …I feel like we hope there will be a dialogue and better relationship between the two cultures at some point, but it seems like this issue will just continue.”

At the beginning of this editing assignment, “I wasn’t fully convinced that Dokdo was a living symbol of the legacy of the occupation, forced labor sexual slavery and all of that. After doing the film, now I am,” Kim said. The people of that generation are now dying out, she said, and as time passes, there are fewer eyewitnesses to Korea’s occupation. The one witness that will be standing after the generation is gone may well be that lonely pair of islands, she said, and its symbolic meaning in the hearts of the next generation.

The Land of My Father website (www.landofmyfather.com) will post updates of future screenings, to be determined, and with links to paid downloads that will be available from film festival websites.