When glass shattered across the street, I left; returning, I saw South Uptown in a new way | By Tiffany Pauling (Summer 2020 issue)

My South Uptown, Minneapolis neighborhood is a gentrified environment where young, mostly white couples stroll the streets, often with very well-trained dogs. The smells of coffee, donuts, pancakes and lilacs permeate the air. I like to take a leisurely walk about a half-mile down to Bde Maka Ska, and loop over to Lake Harriet. When the mood strikes me, I wander over to the Lake Street area to buy groceries, go to the bank, eat some amazing food and otherwise enjoy the comforts of city living.

My lens on this peaceful vision quite literally shattered on Friday, May 29 at the height of the protests over George Floyd when looters came calling for the tiny little convenience store across the street from where I live.

George Floyd had been murdered over on 38th and Chicago the previous Monday on Memorial Day by (now-former) police officer Derek Chauvin as three other (now-former) officers stood by and watched. The whole thing was caught on video by a concerned passerby, went viral, and is now a piece of history as the pivotal moment in a new racial justice movement. The ensuing days saw mass protests, curfews, calls for change and arrests by the community. I watched in horror as I saw and smelled my city being set on fire and also watched over and over again instances of police brutality toward protesters, as uniformed police sprayed tear gas and shot rubber bullets to disperse what had been a peaceful group.

Each night since his murder, I stayed up watching the various live streams, Twitter and local news coverage of the protests. I became anxious when things grew violent on that Wednesday night around the Third Precinct police station and the Lake Street Target. I panicked hearing the glass shatter across the street. Then I left.

I packed a bag with a few clothes, broke curfew and went to stay at a friend’s house. I felt both panicked and guilty for doing it, thinking I should stay. I should be out there, fighting for fellow people of color: Black Lives Matter, Black Trans Lives Matter.

Didn’t I know that Minnesota has some of the largest racial disparities in the country? Didn’t I know that Black people are more often than not profiled by Minneapolis police. Haven’t I witnessed this before during the shootings of Jamar Clark and Philando Castille? The police department truly has systemic racism that needs to be dealt with. But, my heart had been jumping out of my chest for three days straight and my idyllic little neighborhood no longer felt all that safe. So, I got out of there.

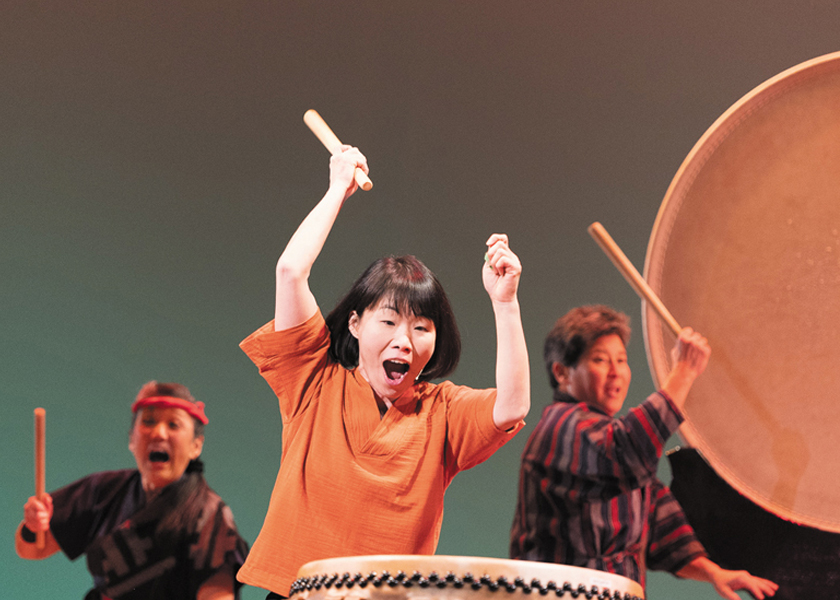

I am a Korean adoptee. I grew up in the northern suburbs of St. Paul in what was, at the time, a 99 percent white community. I’ve had my fair share of outright racial slurs and more than my fair share of microaggressions. However, I had a white family and all the privileges that come from that. I benefited from many advantages, from attending better schools to living in more desirable neighborhoods. I know that as a privileged East Asian person, my interactions with police are very different from those of a Black person.

I also confronted my own confusing feelings of racial identity versus racial bias. Korean adoptees and other interracial adoptees often experience a strange intersection of being the target of racism while also having their own internalized prejudices.

Unfortunately, growing up in a white family also means becoming instilled with a fair amount of racial biases. Since Memorial Day, I’ve been grappling with my own biases and prejudices, like realizing that while the route to Cup Foods is the same distance as my usual walk, I almost never walked in that direction —- out of Uptown and into South Minneapolis.

Walking around the George Floyd memorial in the wake of the uprisings, I met and spoke with various volunteers and speakers. One group of women, including Jessica Ford, Shaynna Bradford and Brittany Carucci, was running a food stand and handing out snacks and water for free. They said that later in the day, they were planning on grilling hot dogs and hamburgers. Another volunteer was standing near the entrance squirting hand sanitizer on everyone who walked in.

was killed in Minneapolis. Photo by Tiffany Pauling

Emotions ran high at the memorial with community leaders speaking on megaphones, church groups singing and individuals voicing their opinions, grief and anger over the situation. Rev. Tommy Russell, an African American minister from Greater Mount Vernon Missionary Church, spoke about unifying the people and the police, bringing peace to the city. Multiple people in the crowd didn’t want to hear good things about the police. One group, upon hearing him, started singing church songs very loudly to try to drown out his voice.

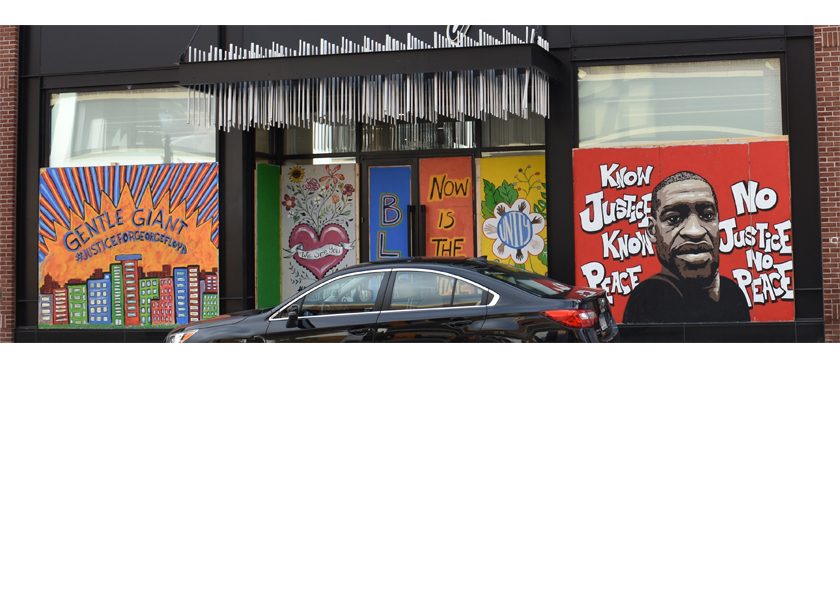

Over in Uptown, roughly two miles from 38th and Chicago, in response to all the plywood boards that had gone up to protect store fronts, artists came out in full force. People were painting the walls with memorials to Floyd, Black Lives Matter slogans and the names of other African Americans who died at the hands of police.

Payton Russell, founder of Spray-finger, a graffiti arts and education program, was working on a piece on the corner of Lake and Lyndale. A father assisted his children with their own graffiti art pieces. As he worked, he spoke about how this is an opportunity to show how graffiti can bring good, and how it can be a way for artists to showcase their talents. He tied it to the struggle for racial equity, saying that people have to get rid of racism and injustice before trying to get rid of illegal and unwanted graffiti.

It continues to jar me to see the destroyed buildings in my neighborhood, like my post office and bank. Slowly, the plywood murals are being taken down, but it will be a long time before it starts to look like my old neighborhood again. Like our entire society, my neighborhood may have undergone a permanent change because of what happened on Memorial Day. In fact, I may never see it in the same way again.

As I engage with my neighborhood again, I am seeing its scarred and beat-up storefronts in a new way, as an epicenter of the fight for racial justice in our country. It has been a scary time but also a privilege to witness what happened here. There are many cities where this could have happened, but it happened here, outside my windows. In time, we Minnesotans may feel gratitude that this reckoning day for racial justice started here first.

Personally, I continue to hope for, and work for, meaningful change which will help do away with the systemic racism against African Americans, and bring hope for better neighborhoods and a better society for the rest of us.