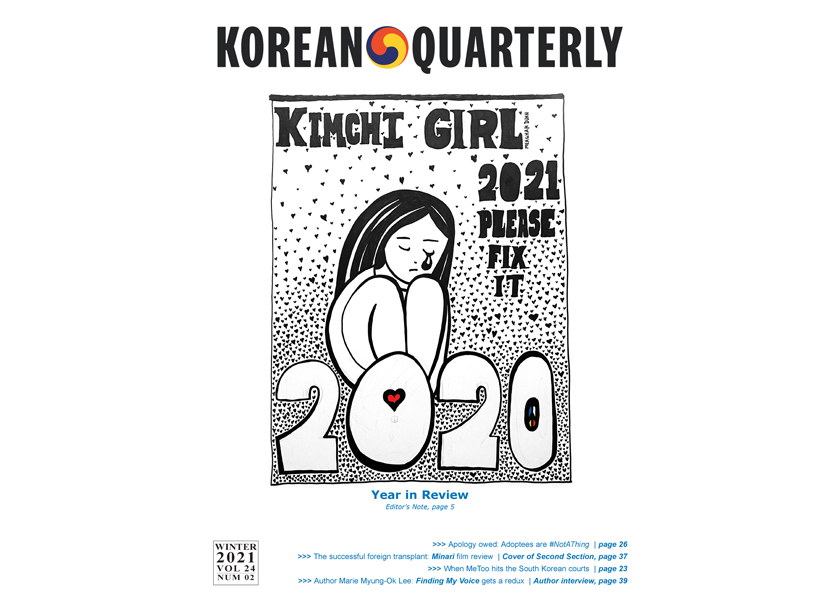

Korean Quarterly’s snippets and snapshots of 2020, the weird year that was | Editor’s Note by Martha Vickery (Winter 2021 issue)

Toilet paper. That is what comes to mind about the beginning of the 2020 pandemic. It was a silly and selfish beginning phase of what became a horrifying challenge for our country. The ridiculous specter of shoppers fighting over toilet paper in big box stores was emblematic. Toilet paper wars stood in for how our normal lives were, in fact, going down the toilet.

We learned quickly how important the many small things in life really are – going to the library, hanging at the coffee shop, hugging our loved ones, seeing our coworkers, going to a play or concert, because those things were suddenly impossible. We complained. We looked at our own four walls way too many times. We grieved the small things. Some grieved the big things, like the loss of a career, or the biggest – loss of loved ones from a disease that left them dying alone.

For all of us our small and large disasters, they all seemed to shrink in importance because so many were happening to others all around us. It was a shared year of loss.

It may be too soon even to have much historical perspective on 2020, or to draw many meaningful lessons from having gotten through it. Right now, it’s more a sense of “What just happened?” like being hit by a truck, and watching it lumber away into the distance.

But this year in review is a chance to look back, on some of the good, bad, and ugly of a very weird year, as seen through the work of KQ’s reportage and its very perceptive contributors.

Winter 2020, before toilet paper weirdness

At the time we published the winter 2020 issue, the toilet paper mania was yet to come. The new virus as something in China, too distant from our reality to worry about yet. Was it sort of like the flu? We weren’t sure, and as we would learn many months later, Chinese authorities were deliberately tamping down release of information they knew about coronavirus at that time.

As South Korea competently ramped up to fight the virus, Americans were told by their fearless leader not to worry, that it would one day disappear like magic. Impeachment was ongoing. Columnist John Feffer wondered in his winter 2020 KQ column whether impeachment would even harm Trump’s chances for reelection, opining that it would really depend on whether the economy would hold steady through the election year. That prediction was partially fulfilled. The economy has tanked, but the reason Trump was not reelected was way more complex than the economy. It was not something anyone could have foreseen.

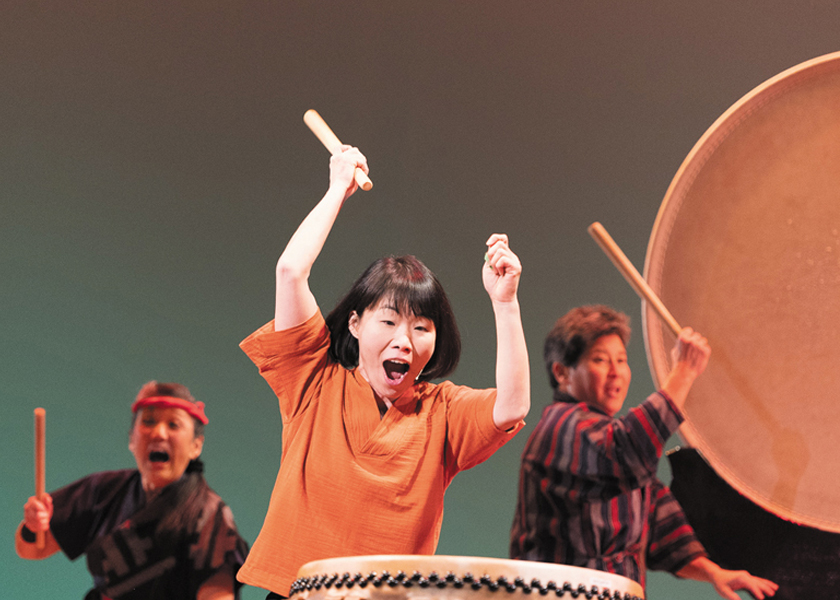

Also in February, KQ covered a once-in-a-lifetime get-together and concert HerBeat: Taiko Women All-Stars. Held at the Ordway Theater on February 29 to a packed house, the event took a year for local taiko artist/instructor (and Korean adoptee) Jennifer Weir to put together with funding, partners, timing, and invitations to 18 of the world’s most elite women taiko drummers. They had to be persuaded to come to Minnesota “in the dead of winter,” Weir remarked. No event like it had ever been held. Documentary filmmaker Dawn Mikkelson recorded the concert and other related events for a documentary film to be premiered sometime this year.

Weir spoke later about how the concert took place, serendipitously and luckily, just weeks before all performance venues had to shut down. If it had been two or three weeks later, it probably would not have happened at all. There is now a trailer for the film in which Weir says something like “This is the biggest thing I have done, ever, and it makes me very happy and slightly ill.” The trailer and other info about the film is available at a new website: www.herbeatfilm.com

Pandemic uncertainty

The spring 2020 issue of KQ had a graphic of three Korean faces wearing masks imprinted with U.S. and Korean flags. By then, the pandemic had arrived in the U.S. but it had arrived in Korea first. Some columnists felt we were headed for a drastic change in our own country, while others observed how Koreans were intelligently beating back the coronavirus through infection control methods (story here), contact tracing, testing, and plain old common sense.

Frequent KQ contributor and artist Lora Vahlsing described how there was uncertainty and change in the air during her trip to New York in early March to take a yoga instructors’ workshop and have some fun with her daughter (story here). One of the visits they made was to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The two went through many of the rooms of objects “from guitars to teapots,” enjoying the feeling of being around so much creative beauty. That night, they found out that the Met had closed its doors indefinitely that day, due to pandemic restrictions. She writes that is encouraged that a pandemic cannot take her creative spirit from her. “Art is necessary precisely because it allows us agency: It both grounds and elevates us, and it can even keep our hearts from breaking during these uncertain times.”

Vahlsing was busy creating during the pandemic year. Some new creations, made of paper, thread and canvas are in an exhibit entitled What the Paper Reveals, at a gallery in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin through March 28.

Columnist Seth Mountain, who writes from the perspective of an American living and working in South Korea delivered the bare truth that so many Americans hate, don’t want to hear and are still struggling with, that coronavirus is a “test for all of us”:

Coronavirus doesn’t care how we respond. But in a democracy, this contagion can only be subdued by people who understand that freedom requires self-restraint and caring for neighbors. The curve can only be flattened by collective effort.

Columnist Christine Heimann, a Korean adoptee from the Twin Cities, works with children through a service organization for adoptees she co-founded, Adoptee Bridge. After seeing Korean adoptee kids be the subject of racist remarks related to coronavirus, a beautiful, spare essay poured out of her that has enough food for thought for a year’s worth of podcasts or perhaps a Ph.D. thesis.

The jist of the essay is that through the ages, there were always racist or homophobic theories as to the origin of pandemics. In the 1300s, Jews got the blame for the bubonic plague, in the 1980s, gay men got the blame for AIDS, and in 2014, West Africans got the blame for Ebola. The flames of racism in the 2020 pandemic were further fanned by Trump as he continued to call COVID-19 “the Chinese virus.”

Heimann wrote with hard-headed commonsense about realities that became clouded by the speculation, suspicion and rumor that was the daily news cycle around coronavirus. “New diseases have been and will always be a part of our lives. We cannot let new diseases (or any new unknown) cause mass hysteria, and most importantly, we cannot permit new and unknown diseases to be an excuse for hate and racism.”

Teachers, actors, restaurateurs, and others who come into daily contact with the public had to either suspend their activities or retool to cope with new structures needed for a COVID reality in 2020. KQ checked in with friends and resource people around the Twin Cities about how coronavirus has affected their lives (story here). One group we spoke with were several people engaged in education, from kindergarten to college.

Laura Sharp, a music teacher and Korean adoptee who works for a school in Roseville, observed how teachers re-tooled a whole system in about three weeks to provide online education, child care for essential workers, and breakfast and lunch delivery to students in their homes. The really tricky part, however, was persuading students to participate in their on-line education.

Some students take to online like a duck to water. Others drop out, and teachers don’t even see them again. Others are just too young. Teachers have a duty to make the online education as accessible and equitable as possible, but they can’t do much about the inequitable living situations some students experience. “That’s the powerful thing about teaching,” she said, “is that you do care about every single one of them.”

KQ also checked in with the Minnesota Theater Alliance, which reported that an estimated 2,933 Asian Minnesotans’ jobs were affected by theater closures that happened in mid-March – they are coming up on a year of closure in March. Katie Bradley, a Twin Cities actor, said in March that her future was uncertain. “Our job is to get in front of a lot of people crowded into one room. We won’t be able to do that now, but for how long? That is the terror, of not knowing.”

Actor Sun Mee Chomet had almost a year’s worth of performances scheduled when all her contracts were cancelled in March, and she was wondering what was next. In the midst of the uncertainty, she was trying to stay grounded and work on positive activities, like learning Korean. “Life is more important than art …and there are things more important than plays. We will come back, but this is one of those times.”

Minnesotan George Floyd, and how it happened in our neighborhood

A couple days after George Floyd was killed on Memorial Day, KQ’s board chair Phil Lee got in touch and asked if he could submit an essay. Because our new online edition had been launched a couple weeks before, we planned to put it on the website because his topic — Asian Americans in a moment of racial reckoning — was so timely, and the shock was still so new.

Lee wrote his essay from the point of view of a Korean American whose north Minneapolis church was mobilized to distribute food, water, and basic supplies to people whose neighborhood stores were burned down in the violence and anger that spilled out after the videotaped murder of George Floyd went viral. While packing and hauling groceries, he had a lot of conversations in early June with people of many races and economic classes.

As a 1.5-generation Korean American, Lee wrote, he has been the subjected to both racism and privilege. Reflecting on how people have asked him “why are Black people looting, rioting, and burning buildings?” he said if police did nothing about a crime committed against his family, such as a child getting murdered, he might burn down a building or do something else to get attention. “For the Black community, it’s not just one child, it’s generations.”

KQ contributor/volunteer Tiffany Pauling wrote an essay from ground zero of the movement to demand justice for George Floyd – her own neighborhood. She also contributed photos of some of the early George Floyd and Black Lives Matter mural artwork in the neighborhood. Pauling wrote that she got nervous when there was violence at the Lake Street Target and the Third Precinct police station (which was later burned down). But when she heard glass shatter in the window of the convenience store across the street from her home, she grabbed her car keys and went to stay at a friend’s house.

Later she attended the George Floyd memorial, spoke to the volunteers, and watched some of the now-iconic murals in the making.

After the memorial, after the crowds left, and she wandered the now quiet, beat-up, boarded-up neighborhood, she was left with conflicted feelings, and in her essay, she described them. “Korean adoptees and other interracial adoptee often experience a strange intersection of being the target of racism while also having their own internalized prejudices.” Understanding that intersection was, for her, a personal racial reckoning in a year of national racial reckoning. Likewise, her neighborhood may have undergone a permanent change. “In fact, I may never see it in the same way again.”

Despite everything, moving forward

Between summer and fall there was a movement to a new normal, in part because of the urgency and the excitement of the general election. Emphasis was on the hard work to push forward initiatives like getting out the vote among Asian Americans in the Twin Cities, and the Reclaiming the Block initiative. There was a sense of getting on with work that needed doing with or without a pandemic.

On the cover of our fall edition were the faces of five Korean American candidates for the House of Representatives, the most that ever ran at one time (story here). Only one, Andy Kim (D-NJ 3rd District), was an incumbent, fighting to get reelected in his swing district where only a few percent are Korean Americans. Of those, four were elected, and will (when they have time) form a small, but presumably mighty, Korean American Caucus, the first in the history. They have now changed their notoriety from the most Korean Americans to run at one time to the most to serve at one time.

The Coalition for Asian American Leaders (CAAL) in the Twin Cities went after the Asian American vote in the Twin Cities with energy and a smart strategy. The online session State of Asian Minnesotans: Fired Up and Ready to Go discussed the challenges of getting Asian Minnesotans to the polls, including language accessibility, and the large numbers of voting age that need to be reached in a variety of ethnic groups. Turnout for Asian Americans has been in the 50 percent range, and 75 percent for the overall population in Minnesota.

At the same session, activist Jae Hyun Shim discussed her work for the advocacy collective Reclaiming the Block. Shim worked with the group over several years to propose ways to shift financial resources away from the huge Minneapolis police budget to other neighborhood initiatives like social services and mental health support. The job took on more urgency post-George Floyd’s murder. Nationwide, while the idea of defunding police has gathered strength in the last year, opposition to it has also intensified, Shim pointed out, as police response has become more violent.

Also, very much behind of the scenes, the lobbying group Adoptees for Justice has been working to get now 91 cosponsors for the bill that would make every inter-country adoptee a citizen with no exceptions (story here). An estimated 18,000 or more Korean adoptees may be without citizenship, according to South Korean statistics. The bill needs only to get before Congress for a vote. A brand new short promotional video and letter of support to sign is now available at: adopteesforjustice.com/supportletter

As Georgia led the way to stop voter suppression and find voters of color to go to the polls, turning the state from red to blue in the general election, it also sent its first-ever Black senator to Capitol Hill. At the same time, Asian American participation has risen, mainly due to similar efforts to get out the vote, in Minnesota, Georgia and other states as well.

As a nation, there has been one reckoning after another. In dealing with white supremacy and the recent insurrection in the Capitol there have been contradictory cries of “America is not like this,” and “no, this is exactly what America is like.” At the same time, diverse candidates are stepping up and winning elections to show the rest of us exactly what democracy can look like.

It has been a year of turmoil, loss and lessons; it has also been a year of getting back to the most important basics of life. Many Korean Americans have reckoned with their own racial identity in an environment of heightened racial tensions. At the same time, there has been a new representation of Korean Americans in politics and advocacy. It is an energy that can no longer stand on the sidelines. With more Korean American leaders and activists to get us through 2021 and beyond, despite everything, the future is looking bright.