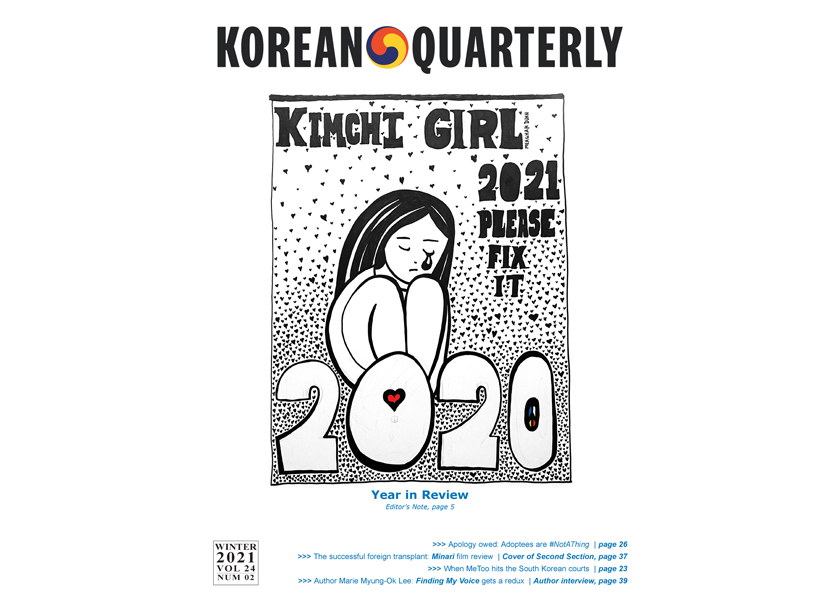

Author Interview: In We Are Meant to Rise, BIPOC Minnesotans write about being at ground zero of a racial reckoning | By Martha Vickery (Spring 2022)

In the pre-pandemic days of 2019, Carolyn Holbrook and David Mura, longtime friends, writers, writing instructors, and collaborators in conducting community conversations about race, put out a call to writers of color in the Twin Cities.

The initial goal was to assemble an anthology some of the life stories shared in the panel conversations held through a community program dubbed More Than a Single Story. However, after the topic was all decided, history unfolded in Minneapolis. Everything changed, including the trajectory of the planned anthology.

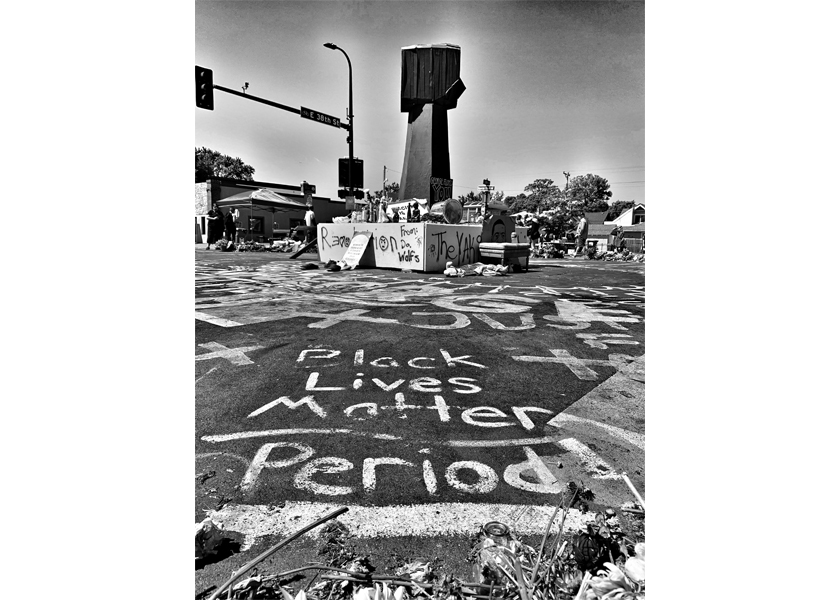

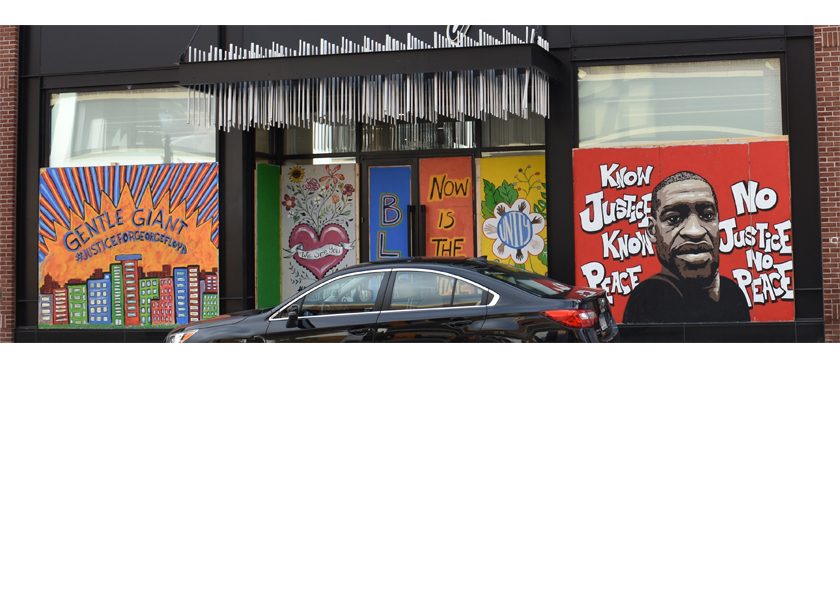

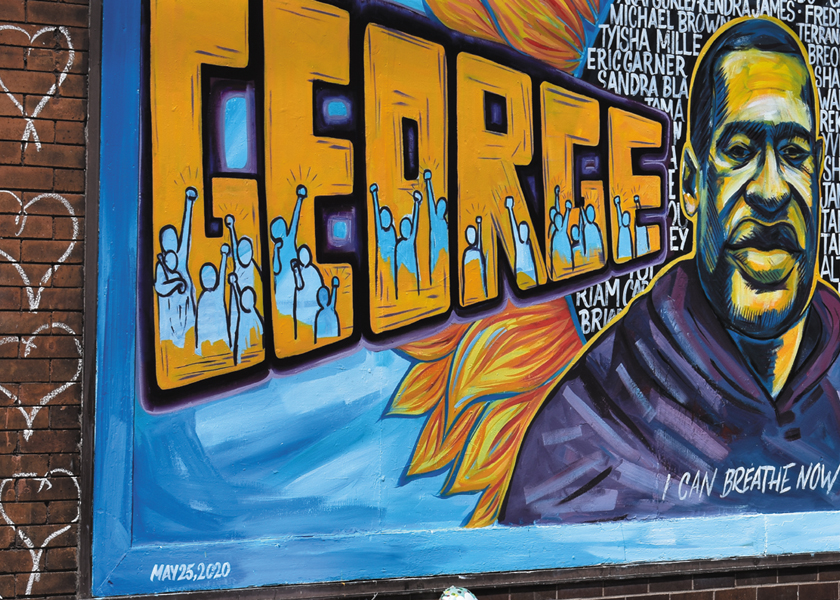

As 2019 turned into 2020, the two co-editors revised their call for stories twice; once to invite the writers to tell stories about the pandemic, and a second time, in the weeks following May 2020, to invite them to write of their thoughts about the George Floyd murder, the demonstrations in the Twin Cities afterwards, and the effect of these events on their lives.

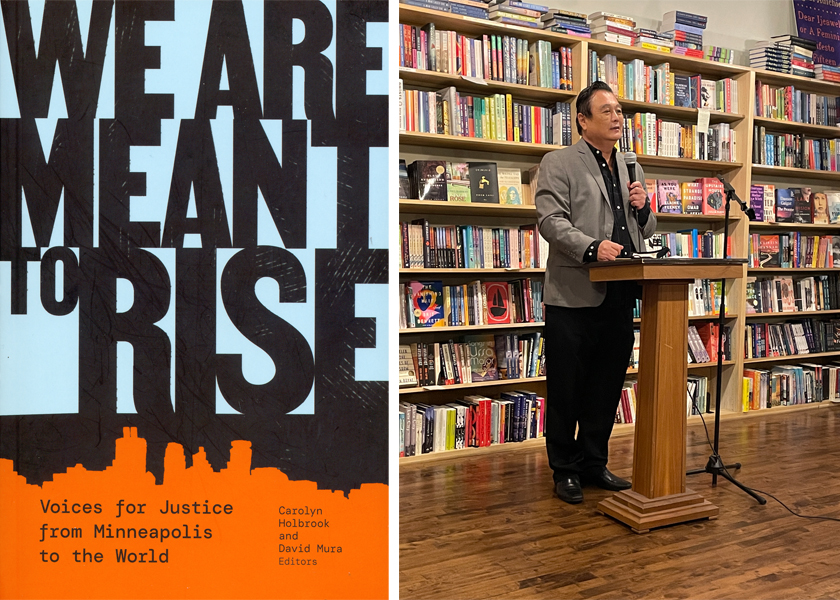

This turning point in history from the point of view of writers living in that place and time is captured in We Are Meant to Rise: Voices for Justice from Minneapolis to the World, an anthology of 34 stories that launched at the end of 2021 by the University of Minnesota Press.

In mid-2019, Holbrook and Mura were well prepared to embark on collecting the stories gleaned from a wealth of community conversations. There were five years of stories from Holbrook’s ongoing panel discussion series More Than a Single Story, originally designed as a panel series for black women of various ethnic backgrounds, which expanded to include other women of color. The program later added a writing component.

This ongoing program collaborates with public libraries, the Loft Literary Center, and other venues. Mura joined the program three years in, designing cross-cultural discussions for men of color, as he has done for other programs in the past.

Inviting the would-be anthology writers to write on the topics of pandemic and racial justice, particularly because many of the participants were Twin Cities writers of color, was instinctive.

Holbrook, a Hamline University creative writing professor, explained that the trauma of the times meant assembling the anthology would take longer than original calendar called for. “There were several people… they were just unable to write for awhile,” she said. “The pandemic affected people in such so many different ways. Many people who just write all the time were just flattened and couldn’t write anything.”

To encourage the writers, she said, “we had a Zoom meeting with several of those people and just had a really nice conversation with them, so that they could try to release whatever was holding them back.” After that conversation, she said “the pieces began to flow.” The editors also personally invited some well-known Twin Cities writers of color to contribute.

The collection in We Are Meant to Rise contains both prose and poetry. It includes first-person accounts of those who witnessed and/or participated in demonstrations following the May 2020 murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis Police. It also takes in reflections of writers with Minnesota connections, contributing their perspectives of how the moment of racial reckoning reverberated with them.

Some writers recall events that happened during the demonstrations, in that neighborhood, such as Melissa Olson, who writes a journalistic account of how she and family members saved a radio archive, 1200 reels of audiotape from 15 years of interviews by the Minneapolis Native American media organization Migizi Communications, by taking them home in her van, while the buildings on either side of the Migizi headquarters were burning. Two days after moving the archives, the Migizi building also burned to the ground. She writes that fire trucks never came.

Other writers submitted first person accounts of how the pandemic and the racial violence have affected them personally. Author/activist Shannon Gibney describes seeing play out before her a version of what James Baldwin wrote in 1962 about “the fire next time,” describing how as black Americans move out of what white society sees as their prescribed place “heaven and earth are shaken to their foundations.”

Minneapolis poet and writer Bao Phi reflects on living in and bringing up his young daughter in the place where George Floyd was killed. He and his daughter lay a teddy bear on the memorial for Floyd, and he describes in his essay how the traumas have penetrated her. He writes that she is afraid of police, and asks him often when she hears a sound at night if someone is breaking in.

Korean Minnesotan poet/playwright Ed Bok Lee’s 23-part prose poem Pandemic Love observes the pandemic loneliness and the impossibility of understanding the moment even as an eyewitness, as he walks around in South Minneapolis in the summer after the George Floyd murder and demonstrations. Holbrook described Lee’s work as “an invocation,” and said she wanted it to be the first piece in the collection, after the introductory essays.

Lee was quarantined with his then three-year-old daughter in summer 2020 in their third-floor apartment, just blocks away from Cup Foods, where George Floyd was killed. Cut off from friends and other family, and many of the usual ways of amusing his daughter, the two of them took a lot of walks, he said, listening to constant sirens, observing what was happening in the neighborhood. Her ability to express herself with words grew fast that summer, and she asked a lot of questions. Amid a lot of confusion, external and internal, he treasures the one-on-one time he spent with his child at a critical time, noticed how their relationship deepened, and how she kept him grounded.

He attaches the word “alone-ness” to how he and others experienced the pandemic amid other new and unfolding traumas. He searched for what was just below the surface of consciousness during the summer 2020 events, trying to get at that level in his poem. “Not a lot of people had the language to process what was going on — it was all coming so fast,” he said, with pandemic confusion, racial uprising, jobs and events cancelled, with parents and kids suddenly at home together. “People were sitting with all these questions, in alone-ness.”

At that moment, Lee said, he was trying to record what happened internally, and it spilled onto the page with what words he could gather up at the time. In five years, he said, he would be able to do a better job, but he felt a duty to write what he could.

Creative writers are “journalists of the interior life as they’re experiencing things — on the streets but also deep within them and within the psyche,” he said. “And not just their own individual psyche but the psyche of society. That is the poet’s and the creative writer’s job.” He describes himself in Pandemic Love as cynical, but writes that “at your core, it’s hope more than habit that gets you up in the morning.”

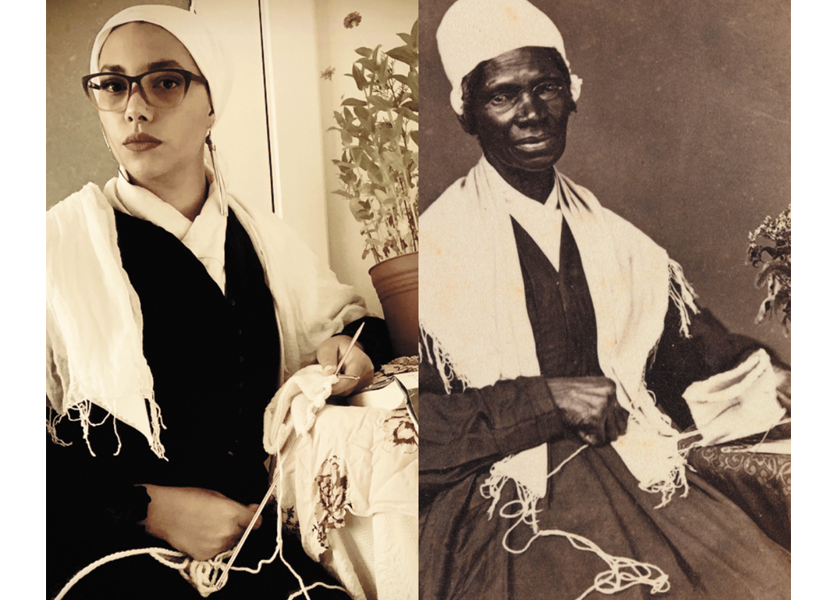

Minneapolis poet/racial justice activist (and Korean adoptee) Sun Yung Shin penned a first-person self-interview entitled A Tangent to a Story About the Smith & Wesson .38, or Attempts to be Fully Assimilated into the White American Project Have Failed Miserably, in the Form of a Self-Questionnaire, in which she is the interviewee, a Korean adoptee who has little information about her origins, and apparently also asking the questions, in the voice of an interviewer who is frustrated that the interviewee seems not to be able to provide the simplest information. With some dark humor, she brings out many questions that Korean adoptees cannot answer about themselves, even “when were you born?”

Shin, who was the editor of the 2016 anthology A Good Time for the Truth: Race in Minnesota, a collection of stories of Minnesotans with racialized prejudice, oppression and violence, said her creative piece for We Are Meant to Rise was freeing in that she could just write on a topic from a Korean adoptee perspective. It was good not to be the editor.

Issues of belonging echo in the Korean adoptee experience, Shin said, and broadly in the community of Black, indigenous and people of color (BIPOC) “in terms of white supremacy and the society that is created and sustained, saying some people belong some places, some people belong in other places, some people don’t belong at all, and some people don’t deserve to live, some people don’t deserve safety.”

This is the paradigm that led to George Floyd’s murder, she said, “which is that an alleged counterfeit $20 bill is more important than a human being’s life,” and that police authorities and other hierarchies get to make those calls.

As an activist, Shin said, her work to educate about racist policies and heal racism has also been through “cross-racial” efforts to do work to “understand, repair, and transform” relationships. She notes that racialization is bigger than just Black and white; it is part of a bigger system that takes in Asian Americans and others of many races. Participating in the anthology was one way to be in discussion with others. She seeks out such discussions, whether virtual, digital, or in person. In-person gatherings are the best, she said, because of the sensitive nature of the topic. Shin will speak at some in-person events for We Were Meant to Rise later in 2022.

Mura describes the collection as a moment of history observed from many angles. The rainbow of perspectives, from people of different ages and generations, he said, as well as the perspectives of people who grew up in the neighborhood or who live in the neighborhood now, make the collection unique. Including descriptions of the racial reckoning by indigenous Twin Citians puts the moment into a broad historical context of white oppression and genocide in Minnesota, he added.

Korean adoptee artists and writers like Sun Yung Shin and actor Sun Mee Chomet are examples of artists who have also become activists in the Twin Cities. Mura credits Theater Mu for showcasing adoptee stories and encouraging adoptee playwrights and actors since the 1990s.

The anthology also showcases the maturity of the literary community of color in the Twin Cities. “It is a very activist and politically-engaged community, also a very diverse community and one that has produced incredibly excellent art.” At the same time, he said, this diverse community is very personally interconnected, even within families. He related how comedian/storyteller Tou Xiong, addressing an local audience, asked how many Hmong folks in the audience had a black family member, and watched many hands shoot up, amid knowing chuckles.

As a Twin Cities resident since 1970, Mura said the notion of who Twin Citians are has undergone some shifts, but that it needs to continue to change in order to reflect reality. South High School in South Minneapolis, Mura said, where his kids went to high school, is now 30 percent white, with the rest indigenous, black, East African, Asian American and Latinex. This indicates that the diversity reflected in the anthology is a realistic demographic mix of the present and future Twin Cities.

“The traditional viewpoint of what Minnesota is comes from Mary Tyler Moore and Garrison Keillor’s Lake Wobegon, and that’s not what this area is any more,” he said.

Lee recalled that after the Obama election, there was mainstream talk that the U.S. had entered an era of a “post-racial America” which meant that ongoing racial tensions got much less attention in popular culture. People of color never bought the “post-racial” notion, he added. Although the same kinds of police brutality and racial tensions have been happening for many years, Lee observed, the George Floyd moment gave it a kind of identity and attention it never had before. Contributors to this collection, and many other artists of color, he said, have grabbed the moment to advocate for greater recognition of longstanding and systemic racial injustice issues.

Lee said the anthology captures a moment in time that is not available to those who did not experience the aftermath of the George Floyd murder as it unfolded in Minneapolis. It is also a testament to democratic ideals that writers of all different backgrounds and walks of life added their voices to this collection. “They are all BIPOC writers, but that’s almost the only thing they have in common,” he said, “that’s why it’s such a good microcosm of the democratization of whose story gets told.”

Events for We Are Meant to Rise will be held later in 2022, and are listed on the website of More than a Single Story, at: www.morethanasinglestory.com. Events are also listed at the website of the University of Minnesota Press, at: www.umnpress.edu.