Pastor Sue Park-Hur discusses a few loaded topics in a moment of emerging racial justice | By Seth Mountain (Summer and Fall issues)

Author’s note: In July 2020, I began a long online conversation with pastor/teacher/peacemaker Sue Park-Hur (who lives in California) from my home in Seoul. Along the way, we discussed faith, identity, power, and also the laughter, color and love that mark a journey of decolonization, incarnation, and liberation. What do these three concepts look like today, especially in the U.S. and Korea, and what might they demand from each of us?

Even to say “how are you doing” is a weird question to ask these days, mused Sue Park-Hur as a way of starting off what she didn’t know then would be months of intermittent conversation with me about topics ranging from whiteness and racial injustice to using language in a way that many groups can access. “We are living in crazy times.”

Part of Park-Hur’s work for the Mennonite Church is “intercultural development competency” with churches, that is, helping churches navigate the many cultures of their community and world. “There are different stages of cultural competency, and one is polarization,” she explained. “There is also what is called reverse polarization, and this includes people who are overly-critical of their own race or culture. It pulls them into the extreme other side.”

In reverse polarization, she said, “everything on the ‘other side’ is good. I think that’s what happens, you know, even with parts of the movement right now, right? …You find progressive white people acting as if no Black person can do wrong. No person of color can do wrong, and we just hate all white people. But that’s not what this is all about, right?”

Park-Hur also co-directs a peace center in Los Angeles called ReconciliAsian, which specializes in “conflict transformation, restorative justice, and trauma healing for immigrant churches.” Being an ally also means knowing one’s own group and history.

She recalled when an organization, Roots of Justice, in hosting a series for women about being a white ally, invited participants to “talk about their insecurities of messing up: How do you be an ally?” she said. “I think white people do need to get together to do the work and talk about their insecurities. Because now they’re so afraid of making mistakes in front of people of color that they’re not learning, or they’re frozen. They’re frozen as they are inundated with information and the systemic reality that they benefit from these systems.”

As much as she has to laugh about this timely problem for white allies, Park-Hur said she “really appreciated that there was space for them to have that talk. Honest, frank talk about fearing different spaces.” Whatever it takes to get more people on board helps, she said, because “this liberative work takes all of us and is for all of us.”

I wondered about how white allyship works in the U.S. at this key moment, and why is there so much positioning among whites claiming to be allies, as if everyone has to have a place or a role. Too often, it seems like the objective is not solidarity, I remarked, but rather showing what one knows about being a woke white person.

The issue of how to use language is tricky when disparate groups are trying to have dialogue, Park-Hur observed. “I am saying something, and we’re using the same language, whether it’s ‘Christian,’ or whether it’s ‘anti-racism,’ or whatever, we’re not always talking about the same thing, right? What we’re talking about is God, and forgiveness.”

Real dialogue also requires having a common glossary of words, Park-Hur said. “For a lot of people of color (or BIPOC), when we’re talking about racism, we’re talking systemic issues. And I think a lot of white people just think about it on a personal issue level. So, basically, when we’re talking about this, for many white people it’s ‘are you calling us all racist?’”

Racism is not confined to the U.S., Park-Hur said. “I think about this problem also with Korea, and especially North Korea. We have similar struggles of meaning and language when we try to raise awareness about Korea here in the States. It’s just that in the U.S., there’s almost no basis for us to even have a common dialogue about North Korea, right?

“Some people are so good with words,” she said. “Like those woke white people that you were talking about. They are so smooth, so you think they get it, and then you realize they don’t get it.”

“Forever War” narratives, church life, and memory

Park-Hur also discussed the Korean War as a “forever” war. I pointed out that of course we can say the war goes back further than 70 years, by half a decade, a decade, or many decades, depending on which angle we’re looking at. But, we agreed, “it remains and permeates everything.” In this “forever war” context, we discussed an unusual series of events: I detailed how “right as the uprisings in response to the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis officer were really hitting the news in the U.S. and getting covered in Korea, the U.S. Embassy was suddenly flying the Pride and the Black Lives Matter flags.”

I discussed from my perspective as an American resident of Korea, what it was like to see the reaction of U.S. officials in Korea in relation to the global outcry of “Black Lives Matter.” The U.S. Ambassador Harry Harris even made a progressive-sounding statement. But, as I asked Sue, “I wondered what is real here? What is not real here? What is performative?”

While the U.S. is displaying all the progressive flags, there are activities ongoing that showcase the imperialistic attitude of the U.S.in Korea. For example, the grandmothers living in Seongju are getting displaced so that the U.S. military can upgrade and install its THAAD anti-ballistic missile defense system, an action completely tied to U.S. military dominance of South Korea. Meanwhile, media and staff at the U.S. embassy are applauding these socially progressive symbolic actions. And then a few days later, both flags were taken down. I commented that, from a radical, anti-colonial, Korean viewpoint, this behavior can certainly appear hollow and perverse. Indeed, “perverted” is exactly how one of my closest Korean activist friends described her feelings about the entire displaying, public commenting on, and taking down of the BLM and Pride flags by the US embassy.

Park-Hur said the fraught history of power in Korea was at work in these attempts to show progressive support from its position as an occupying power. “I’ve been there a couple of times,” she said referring to the U.S. embassy neighborhood. “It’s a weird, whack place. Those examples are potent and complicated.” The U.S. thinks about branding when acting in South Korea, she said. “And branding is really big. You also have to seize the moment, right? This is a time where you have to do the right thing, and to show that we are up to date, and aware of what’s happening. Again, to appease, but also hoping this is not how things will stay, right?”

As a person from a divided, occupied homeland, Park-Hur continued, “my heart breaks when I think about it.” She related that she was recently called on to answer the simple question ‘where do you call home?’ as a self-introduction in an Indigenous People’s circle group.

Her initial answer, she said, was “as an Asian American, it’s hard when people ask where you’re from.” However, she knew the group was asking for something deeper. “I just said, you know, my heart always feels divided. My country is divided. And living in America, you have to compartmentalize yourself, and divide yourself into many pieces to survive, right?”

“I’m acutely aware of the layers, knowing this history,” she said, “but again being reminded through different anniversaries and such, that this is not normal. The boundaries are not natural. Somebody drew a line. And it wasn’t even debated.” Is the Korean War now the “forgotten war,” as it is sadly nicknamed in the U.S.? “Forgotten by who?” she asked. “It is forgotten by the people of the empire with power, but the Korean people have not forgotten and live with the consequences every day.”

With statues of past colonizers coming down, and the renaming and reclaiming of place names to honor indigenous peoples, many elements of current decolonization struggles for justice in North America have recently begun to swell into mainstream consciousness.

The struggles are not new, however, but taking them seriously requires more than mentions of land acknowledgements (i.e., a mention of the fact that a place has a native name and was traditionally native land) or inclusion of other new vocabulary in social justice lexicons. What does decolonization demand of all of us generally, and each of us specifically, who are living in a settler-colonial state?

I set up the discussion by asking “How much of this naming is about power? And controlling narratives? How are you affected by the current narratives of being Asian American? Or of being a Christian leader? Or of being a Christian woman leader in a peace church tradition?”

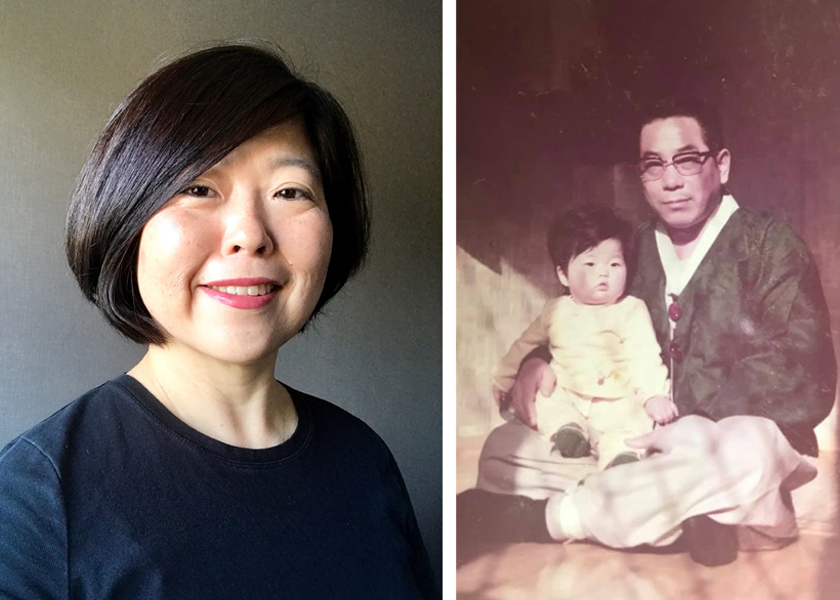

“I’ve been trying to do a lot of decolonizing work on my own,” Sue Park-Hur said, “of my story, of my narrative that I’ve claimed as my own as a settler immigrant. And to deconstruct that has been complicated. I have been tracing back how we even came to the States. In 1980, on May 9, we all came. My aunt invited us. She didn’t have any of her side of the family in Los Angeles for nine years. Then in two days in May 1980, all of her four siblings and 19 members of their families were with her.”

There was a lot of political intensity in South Korea in the year the family immigrated. Park-Hur remembered, as a child, seeing extensive coverage of military dictator President Chung-hee Park, who was assassinated in late 1979 by a close associate. She knew that her family left due to the political unrest and the opportunity of her aunt’s invitation to come to the U.S. Upon digging more into her history, Park-Hur learned that her aunt’s sister-in-law was married to an American GI. “This was another piece of imperialized history that was directly connected to my story. I was able to come to America because America came to Korea.”

Another branch of the story is about her dad, Park-Hur said. Born in 1933, he was 18 (in the Korean age-counting system, 17 in Western age). He enlisted, fought in the war “and then he had PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder] all of his life, that we were not able to name until he was in his 60s.”

Her dad could not hold a job in Korea, Park-Hur said, “so my mom worked, and again, there was a shame factor, right?” Her father heard voices, “mostly the voice of his former military commander, for most of the rest of his life,” Park Hur recalled. “And so, when he had his episodes, he would drive strangely. He’d be driving and I would be like, ‘Dad, we need to get off the freeway!’ And he wouldn’t because he’s hearing a voice that’s telling him to go make a left and a right, and to go in circles.”

Park-Hur said she lived with that kind of “insecurity and not knowing quite how my dad was going to respond, day after day.” Everybody knew, yet no one talked about it, she said. “We had these code words. ‘Oh, is dad sick?’ ‘Yeah, he’s sick.’ I’ve thought a lot about why we did that. It was a way to honor my dad. He was not physically abusive to us. He was emotionally abusive because of his illness but again, we had no words for PTSD until later, right?”

The shame of mental illness in Asian culture kept the family quiet about their father, even with one another, Park-Hur recalled “I realized later that there must have been a whole generation of people like me! People who never talked about it, who were and are probably still suffering from the trauma of war. If you’re a gentle, normal 17-year old teenager, and you’re suddenly uprooted and seeing blood and slaughter – how could you stay sane, right? So, for most of his life he suffered.”

To make up for her dad, Park-Hur said, her mother “felt she had to overcompensate, and she was never home. It was my grandmother who came to all the yuchiwon [kindergarten] parties, and all the undong-hae [sports competitions] and stuff. …And I hated and felt embarrassed that my grandmother had to go in place of my mom.”

Coming to America was a second chance for her family, Park-Hur recognizes, but she still ponders many questions. “…we’re grateful. But who created the situation so that we had to come? And why was it that my dad had to suffer?”

Her learned attitude after immigrating, she said, was “Thank God I’m in America! Thank God I had a chance. And thank God my brother and I could be educated. And we could A-B-C, right?” But in more recent years, her older self has reflected on this, and wondered “’I have gained much, but what have I lost?”

In learning the gains and loss in her life, she became more curious, and the story became more nuanced. “And so, I’ve been re-narrating my story, to tell the full truth as I am learning it. …Yet I am grateful, to have this life, to live in such a moment, as an Asian American woman, in a Mennonite church, and as a faith leader. I also mourn that I can’t be in a Korean church where I can be fully myself, and where I feel like I can use my gifts the most, knowing that culture. But it’s a patriarchal, Christian culture that will never accept me fully, in the faith, as a reverend, right? You know Mennonites, we don’t like using titles. But when I’m in a Korean context, I am intentional about my reverend title!”

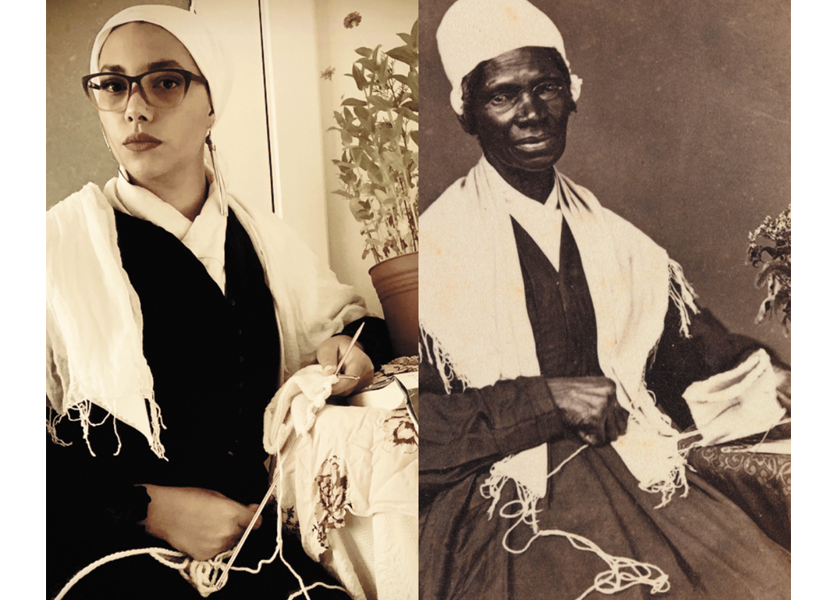

Park-Hur persists in representing who she is, to other Koreans, particularly. “To say ‘this is what a woman pastor looks like!’ And ‘I’m a mother and I am a pastor.’ I think this visibility is important because I want to make space for other women, other Asian American women, and faith leaders, to be like, ‘Oh! I can. Maybe I’ll be like her! …Maybe I can lead the church too.’”

Park-Hur lives with the tension as creatively as she can. “I feel very blessed, but then also, it hurts,” she said. “Why can’t I be where I feel like I’m most at home? Whether that’s the church, or whether that’s being in America, having the privileges that I do. Just the fact that I can speak English, as my heart language, is you know… sad!” she said with a laugh. “Right? It’s sad, and yet I’m blessed because I can have access to different platforms because of my Westernized education and experience.”

“I live with that division, and I live with that dichotomy, wanting to integrate,” she said. “And I think the best way to do that is to know my story better. And not just my testimony, but to be able to put that in context of history, put that in context of economic push-and-pull and all the social, political, economic forces that shape who I am.”

Being a woman of color is a “rare commodity in a way.” Realizing that, using that power, and getting beyond the real risk of being “tokenized,” has been a learning moment. “That has also empowered me to learn how to be who I am and to just be stretched. I am being stretched all the time. And I am not just in an Asian American or Korean context, but I am having to put myself out there more, on the national level or in inter-cultural, inter-racial dialogue. This pushes me, again, to continue learning to narrate my story, and to better understand how I am a product of these struggles, and how these threads help me to connect with others with different backgrounds. To know one’s own unique story rooted in history, I think, is one of the best ways to be a faith witness and leader.”

Knowing one’s story is a start of ministry, “and somehow that call for the ministry of reconciliation is still at the heart of who all of us are called to be, including me.”

Decolonization, incarnation, liberation

In terms of decolonization, I reflected that as Eve Tuck [academic who co-authored a well-known article on decolonization and repatriation] famously said, ‘decolonization is not a metaphor.’ It can’t be something else. It can’t be subsumed by other narratives, even by the narratives of justice that we have. One must ask “what kinds of incarnation and liberation are possible without decolonization,” as well as how can we be “active participants in decolonization, incarnation, and liberation – of the spirit, the body, the land, the narratives?”

Park-Hur said she had a recent deep conversation about “enemy love.” Specifically, it delved into how are we to understand Matthew [chapter] 5, in which Jesus tells us that rather than love our friends and hate our enemies, we are to love our enemies and pray for those who persecute us. “How do we contextualize that in our understanding of our relationship with North Korea, and the work that my husband and I do with ReconciliAsian? How do we understand this language of “enemy” in our relations with North Korea?”

Indeed, she affirmed, “North Korea is not our enemy. They are our brothers. They are our sisters. They are people who are in pain.” However, she said, that was a hard conclusion for her. “I’ve been doing this work for so long, but there is still a part of me that has always seen, and has always correlated, North Korea as my enemy. It made me think about ‘who are the ones that have given me this message that North Korea is my enemy?’ And ‘why is it so hard for me to declare that they are not my enemies?’”

Extricating oneself from this mindset is a process of decolonizing one’s thoughts. “It made me think about the process of how I’ve been taught. How have my thoughts been colonized? Because of my lack of historical understanding, I could not understand why these things are as they are. Living in America, as an ethnic Korean, I grew up not understanding the depths and complexities of the history I embody,” she explained. “I also lived with a lack of awareness of the U.S involvement in the Korean War, the benefits that the U.S. has gained from the division, the placement and proliferation of military bases, and the U.S military industrial complex multiplying after the Korean War. These are things that I had not pieced together until I was in my 30s.”

Decolonization – in theology, and in our understanding of history “is critical work,” she said. “And it is work that I feel called to continue to learn. …It’s really personal as well. I have three children. I want them to recognize scripture, I want them to recognize their callings, and to have a deeper understanding of history than what I’ve been taught.”

Hope, laughter, and seeing people in full color

Park-Hur related a memory of her son’s first trip to North Korea as a senior in high school. Upon returning, he said he expected North Korea to be “very gray, drab, and covered in cement,” but when he got there, everything was “full of color.” She pointed to that description as a “really vivid example of the process of decolonizing. We are seeing people in full color.”

She said her husband reflected on laughter as resistance after a recent trip to North Korea. “Laughter is a way to come together. It humanizes us, the fact that we can laugh together. It is an important part of resistance and decolonization – going back to the talk about enemy love – to imagine breaking bread or eating rice together.” Her husband described laughter in the restaurant that night as so raucous that the owner came out to see what was going on. “The minders [North Korean officials assigned to monitor foreign guests] said they had not laughed so much since college.”

Seeing people in color, without their labels, unburdened by ideology, one-on-one, is a simple goal, but it can be a complex process for an individual to get there. Decolonizing our minds, she said, allows us to “build a new reality that is closer to the Kingdom of God – that is what excites me, and that is the work that we do. …And we have to have the freedom to speak, to speak about the past in new ways, to name truth more fully.”

People with decolonized minds can also freely speak truth to power. In a Korean American context, that truth is “to help people recognize that the U.S. has a huge part in keeping North and South Korea divided, and the ways in which the U.S. resists ending the Korean War and signing the Korean Peace treaty,” she said. “It is a political act, but it isn’t just political. It comes from our conviction and our faith in truth and setting people free with a message of liberation – which is all about Jesus.”

After 2020, “a really rough year,” Park-Hur said, the present “time of unveiling’ is “helping us to recognize the false power that the U.S. has. In our election, in the way that we have dealt with the pandemic, in the way that we have handled or denied our history of racism, all of these things are unveiling. I think it’s an opportunity for us to decolonize our minds, and to reconsider our history. And I think the real hard work will not only be to deconstruct, but to construct a new way to peace, to envision a future.”

Sue Park-Hur was born in Seoul, Korea but has been an immigrant settler in the land of Hahamong’na, part of the tribe of the Tongva people, in what is now Southern California. She works for the Mennonite Church USA as the denominational minister for transformative peacemaking. She is an educator, church planter, and an ordained pastor, and also co-directs a peace center in Los Angeles called ReconciliAsian, specializing in conflict transformation, restorative justice, and trauma healing for immigrant churches. With her husband, Hyun, Sue feels most humbled by their three children who remind them that peace begins at home.