One Minnesotan connects with Atlanta Korean Americans post tragedy | By Mae Ouhr (Spring 2021 issue)

Mid-February 2021, I had just lost a long-time friend. The third in three months. Preoccupied with grief, on March 16, the first words out about the Atlanta spa murders only grazed my consciousness. My body connected to the upheaval before my mind did. My realization of what had happened there unfolded over time.

I read a few headlines late Tuesday. “Not another shooting…” I thought. Wednesday, the rest of the information trickled in. A witness quoted in the South Korean Chosun Ilbo newspaper heard the 21-year-old killer, Robert Long, scream: “I am going to kill all Asians” before the shooting at one of the three spas he attacked that day. Atlanta police Captain Jay Baker explained the killer’s motive to the nation sympathetically: “He was pretty much fed up, and kind of at [the] end of his rope, and yesterday was a really bad day for him and this is what he did.” From the police captain’s perspective, killing eight people (half of whom were Korean) seemed like nothing more than a tough/bad decision. An accident. Our lives might just have to be sacrificed for a 21-year-old’s bad day.

There were so many layers of rage and grief in reading the shooter’s declaration of hate. I am an adoptee. I grew up in a small town where I was the only minority in the entire school. I was no stranger to racial jokes and slurs, physical assault, discrimination; starting around age six. My well-intentioned white family did not understand, would/could not support my racial experience growing up. Before I learned to love my ethnicity, I had already spent four-and-a-half decades internalizing racism that became self-hatred. Ideas about being Korean made me very uncomfortable and alienated. The closest thing that I had to Asian pride was acknowledgements of my race through self-deprecating jokes.

Growing up, I had conversations about race that included whitewashing, such as “Everyone is the same/We don’t see color.” I noted inaccurate perspectives of post-racial America: “We marched for civil rights back in the ‘60s, so racism isn’t a problem in America anymore.”

I also heard a lot of denial, because, for some, making a problem invisible is the next best thing to solving it: “Why do you have to bring that (racism you experienced) up? Are you trying to upset everyone?” “Can’t we just have a nice time? You ruin everything.” “Get over it.” “Forget about it, keep working, you will be fine.”

I also was subject to outright gaslighting: “Racism is probably just in your head.” “You don’t know if that (bad behavior doled out to the only minority in a group) was racism. Don’t be like that.” “You are handicapping yourself by thinking people are against you.” I was conditioned to never play the race card.

I’ve worked a myriad of customer service jobs. Dealing with micro-aggressions, blatant racism, and intrusive questions affected me and continued to shape my ideas about the way others see me. The dreaded question “Where are you from?” sometimes included every ethnicity except Korean. I was asked if or routinely told that I looked Japanese, Chinese, Vietnamese, Hmong, Thai, Cambodian, Laotian.

I knew there were many Asian countries, but in America, Asians are perceived as “all the same.” Remembering Vincent Chin, I knew this could be fatal to people with faces like mine.

In 2018, decades after Hallyu the Korean Wave of pop culture, that also made Korea and Korean-ness visible, I returned to the Motherland. I learned to appreciate and take pride in being Korean for the first time in my life. In early 2020, I was one of the people who initially did not think the coronavirus was a threat. I perceived the first threat to be the immediate rise in violence against Asian people. When people I knew referred to COVID-19 as the virus from Wu Han, or the China-virus, or spoke negatively about China’s government, I would get upset. This was not because of national politics, but because I already was starting to fear for the safety of Asian Americans.

In 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) amended guidelines, advising national authorities, science and medical communities to not name diseases with terms that include: “Geographic locations, cultural or population references, or terms that incite undue fear” (WHO, 2015). A disease named after a location motivates backlash against people related to that place, which can include violence and murder. Yet some white friends, who claim to be liberal, still did/would not recognize how calling COVID the “China virus” exacerbates the threat to all Asians.

Asian Americans have been assaulted while grocery-shopping with infants, taking out the garbage, walking their dogs, going to work, sitting on the bus. In seeing so many headlines reading “Asian attacked” or “Asian assaulted,” the only commonality that I saw was an Asian face scapegoated. I know what I saw. I recognized it. And I recognized the denial by the media and law enforcement denying these were hate crimes. It was a very old and familiar frustration. I read of repeated acts of racism followed by public denials of prejudice in America. In a way the truth made public was finally validating, but it was the kind of validation that I never wanted.

When Atlanta happened, my body physically reacted with shock, trauma and grief beyond what my brain was able to comprehend. It’s impossible for me to discuss Atlanta without relating it to George Floyd, and most recently Daunte Wright. Injustice to one is injustice to all.

When I just turned 21, one of my first Black friends explained to me why they would not tolerate anti-Asian/any racially hateful statements. He was one of the first persons to verbalize the idea: “I don’t tolerate anti-Asian talk, because the same people that call Asians “ch###s” use the n-word behind my back.” I felt I found my family. I started to learn about solidarity.

George Floyd was my age, we both worked in security around town. I felt connected to him. Perhaps it was because of these parallels that I was putting myself in his place as a person of color. For that and other reasons I can’t name even now, his public execution by police affected me. Deeply.

For about half of the summer of 2020, I couldn’t sleep more than a few hours. I was experiencing hypervigilance. Since I couldn’t sleep, I read, and learned quite a bit about trauma and the sympathetic nervous system, as I tried to make sense of what was happening inside me.

Following the Atlanta mass murders, I recognized this reaction returning. For the first four days, I would cry every morning, and throughout the day. By end of the week, I would only cry once a day. Progress. I constantly was frustrated and angry. I felt isolated. Alone. Enraged at the police press release that sympathized with the murder; “news” and law-enforcement that still insisted “there was no proof that the Atlanta shootings were hate crimes.”

One day, I offhandedly mentioned I felt like going down there. That thought, that verbalization, sparked the first alleviation of anxiety, stress, anger and frustration that I was feeling. I mentioned this to a few more people. On a Korean adoptee page, somebody I didn’t know offered to let me stay with their family. The more I started to plan, the less despair I felt. I wanted to go and see for myself what was really going on. I wanted to see Koreatown in Atlanta. I wanted to show up in solidarity for my community. I wanted to connect with some organizations, and bring back knowledge to help people in my city. I wanted to eat Korean BBQ.

A few nights before I left, I participated in a Zoom meeting with AFAB (Assigned Female At Birth) Korean adoptees from the west coast, east coast the southern U.S. and Europe. It was such a relief to be able to talk about the tragedy without having to navigate any white fragility. It was no surprise that our reactions were almost identical. Though the group members were different ages, occupations, adopted family experiences and religious/political backgrounds, we all were crying, anxious, unable to sleep, frustrated and exhausted. Even among those isolated from any incidents of anti-Asian hate, we felt the same, around the world.

I did not have many expectations. It was raining the day I left. It rained every day that I was in Georgia. I visited my first H Mart (an everything-Korean franchise super-store) in Atlanta, and then we went to Gold Spa and the Aromatherapy Spa. Approaching Gold Spa, my mind went momentarily blank. My shock melted into sadness, seeing the gigantic word “L O V E” arranged in the parking lot, constructed with tree branches and flowers. So many flowers. Signs. Messages. Memorial offerings. I read notes about each person lost. That was the most difficult. The pain of their families was my pain. The loss of their community was loss of my community. It was the loss of our family, our community, uri, (“our” in Korean) grief had rippled around the world. People could try to deny or ignore it, but our bereavement did not care, and did not rest.

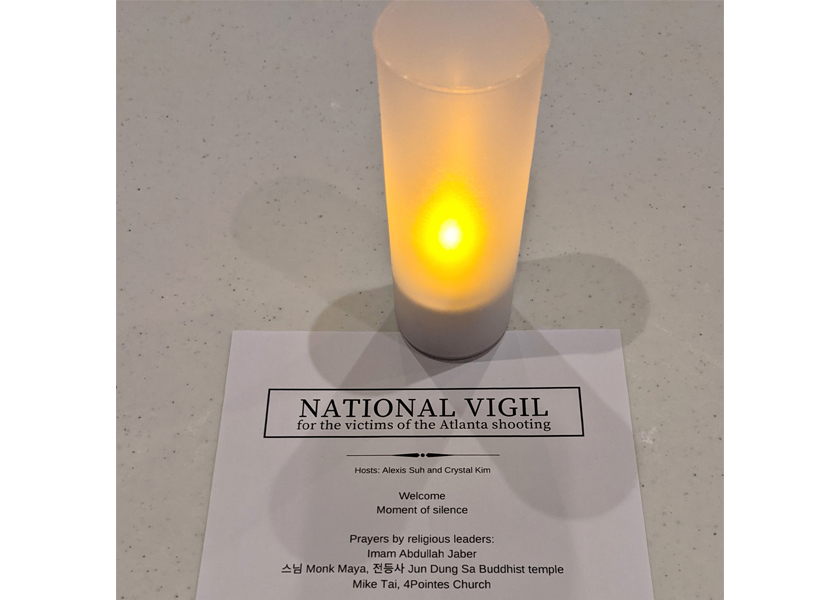

I also attended a conference at the Korean American Coalition (KAC) in Atlanta. Researching different Asian organizations in Georgia I noticed KAC did not list an address on their website. I assumed it was for protection of the building and Koreans who were there. KAC also held a vigil, which was grounding. There were prayers from Muslim, Buddhist, and Christian denominations. The Black and Jewish community showed up to represent, offering solidarity. There was music and poetry. There was a healing strength in unity.

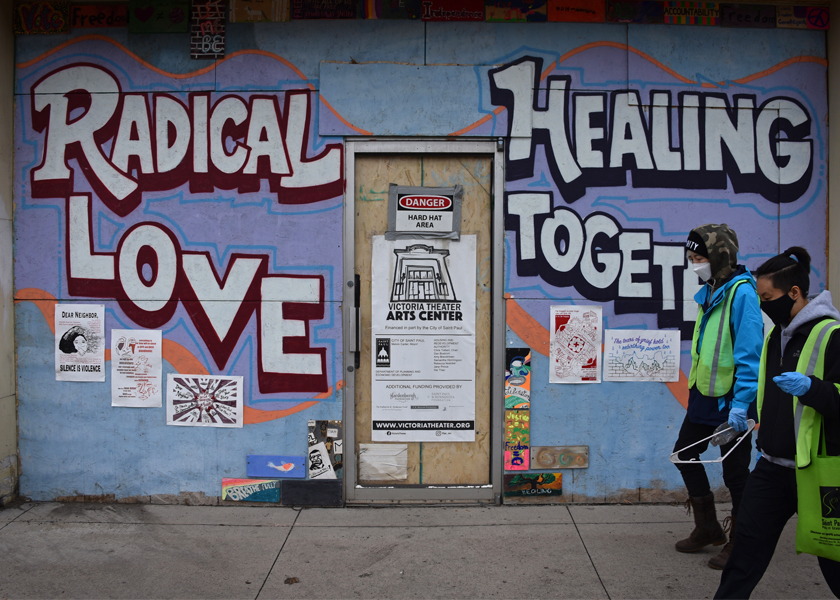

Takeaways: It is important to reach out to like-minded people, and that positive activity can decrease negative rumination, depression, anxiety and anger. I found like minds in the Twin Cities through the Minnesota Asian Safety Squad. The Asian Safety Squad is a volunteer group that does community security walks in the Frogtown neighborhood of St. Paul, in a popular Asian American shopping district. It also offers free rides to elderly/differently-abled people in need. Even walking together for this shared purpose has been very meaningful to me.

In all of our struggles, we are all interconnected — like it or not. As individuals, our struggles may be different, but there are important intersectionalities. We have more in common with each other than we do with our oppressors. Now is a time for change.

The old ways of avoiding racism as Asian Americans, to “Put your head down, let go/get over injustice, and keep working,” are not the path to safety that we were once led to believe. Not anymore. At this point, upholding silence and endorsing Asian invisibility has gotten us hunted and murdered. We (Asian communities and all marginalized people) need to continue to connect, adapt and evolve. We need to be seen, heard, recognized and respected. We need to lose the “divide and conquer” mentality.

Today, I had three work meetings discussing diversity, equity, inclusivity. I experienced the healing power of connecting, and I gained strength in just discussing our truths. Lived experience is real. People, both Asians and non-Asians, are learning about anti-Asian discrimination. Asians are coming to grips with the racism they have battled and navigated their entire lives.

Atlanta has been an awakening for many people. Now is a time for world change. We have a chance to redefine ourselves, and fight for our right to exist in peace. Unity is the only way. Solidarity for the win.

Lastly, demanding accountability of our police, politicians and our own communities is part of that. The status quo model of how marginalized communities and what we will put up with as minorities in this culture is not working. What is the definition of insanity? Repeating these same methods, expecting different results. We need to demolish and reconstruct. The disaster of COVID has left some benefits in its wake, including the opportunity to rebuild something for our future. Let’s build.

Inside the chaos, build a temple of Love. ~ Rune Lazuli