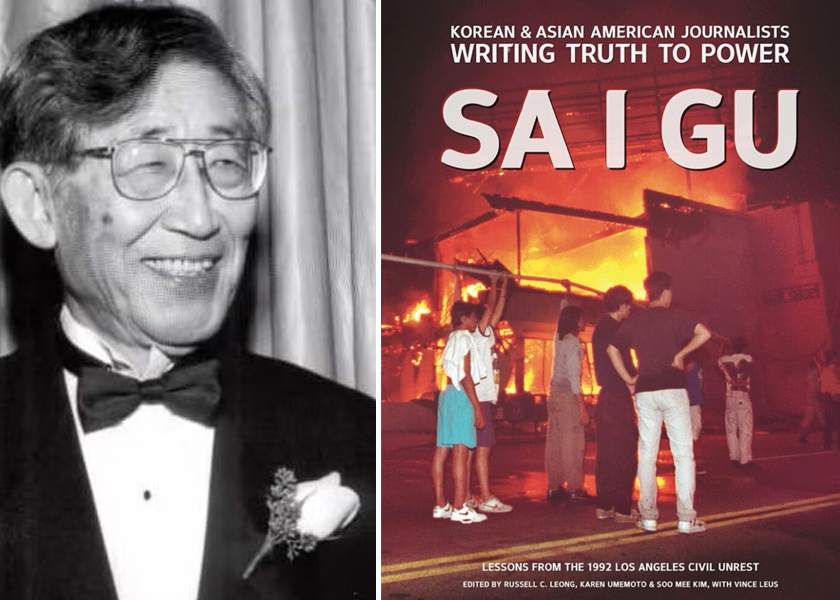

Sa-I-Gu: Writings of journalists on the streets of the LA riots, 30 years on ~ edited by Russell C. Leong, Karen Umemoto, and Soo Mee Kim; with Vince Leus

Korean and Asian American Journalists Writing Truth to Power

(UCLA Asian American Studies Center Press, Los Angeles, 2023, ISBN #9-780-9340-5256-6)

Review by Bill Drucker (Summer 2025)

This informative collection of essays and images presents the events of the Los Angeles civil unrest that began April 29, 1992 (in Korean, known as Sa I Gu or 4 -2 -9). Many of the contributing writers were also journalists at the time, reporting and photographing the horrific events that extended for six days of burning, looting, and killings. The contributing articles include retrospective writings, reflections on Sa-I-Gu after 30 years, and thoughts of social and political reforms that arose from the turmoil. This collection is an excellent reference, with many images and selected reprints of newspaper articles from the time.

The contributing 21 editors, journalists, activists, photographers, artists, filmmakers, historians, and other scholars also reevaluate the causes and consequences of the events. The retellings are vivid and the reflections offered are heartfelt and thoughtful. The photographs capture many disturbing, violent, and tragic moments.

People in the middle

A few famous incidents arising from racial tensions at this time in Los Angeles history became well known – Rodney King, Chol Soo Lee, Eddie Lee, Latasha Harlins and Soon Ja Du – and represented the societal conflict, racial inequality, media bias and injustice of that moment.

Rodney King, a Black Los Angeles man, was perhaps the most famous survivor of racialized violence. He was captured on video being beaten by the police after a traffic stop. The King incident pre-dated the ‘92 Riots, but the acquittal of five police officers who beat him was a catalyst of the April 29 riots that spread across the Koreatown area of Los Angeles. King had his day in court, was awarded millions and for a time became a spokesman for the movement against police violence.

Korean American Chol Soo Lee was not directly involved in the LA Riots, but he was a victim of racialized injustice. He was falsely accused of the murder of a notorious gang member, convicted, and put one death row in 1972. During his incarceration, Lee killed an inmate in self-defense.

The Korean and greater Asian American communities rallied in support of his exoneration, and with added effort from the Free Chol Soo Lee movement and due to the writings about the appeal process by journalist K. W. Lee, supporters raised the funds needed for his legal fees. Lee was acquitted and released after 10 years of incarceration. He received no apology or compensation from the state.

K. W. Lee’s role was indirect, but the Chol Soo Lee movement to support him galvanized Asian Americans in a quest for justice that was a wake-up call that LA Koreans needed to stand up for their community in the wake of Sa-I-Gu.

The Latasha Harlins and Soon Ja Du incident sparked anger among Blacks in South LA. The shooting of 15-year-old Harlins, who was Black, by Du, a Korean merchant, over a minor shoplifting incident, shocked the community and the nation, but was symptomatic of the strained relationship of the Korean and Black communities.

Du was convicted of manslaughter, and got a light sentence hat angered the Black community. Du’s liquor store was targeted during the ‘92 riots. Afterwards, the store was not reopened, and the family moved out of the LA area.

The story of Eddie Lee, a 19-year-old Korean American, is equally tragic. He was shot in crossfire while trying to defend a pizza parlor from looters during the riots. In the hectic confusion of the riots, the shot that killed Lee may have been from an armed local merchant, not by looters and not by the police.

Stories from the streets

The book has four sections that describe political and social environment of the times, look at what was reported in the heat of the moment, describe the notable contributions of journalist K.W. Lee, and add a broad swath of recent reflections, 30 years on, by journalists and other commentators on Korean America, on what came about as a result of the upheaval.

Journalist Kay Hwangbo makes some key arguments about the dual injustices suffered by Black Americans coupled with the scapegoating of Korean Americans in 1990s Los Angeles. She argues that racism was visited upon both groups and that the political and economic systems were racist and that those systems turned racial groups against one another.

Journalist K. W. Lee, who was editor of Koreatown Weekly (1979 -1984) and Korea Times English Edition (1990 – 1993), notes that the events that began April 29, 1992 did not erupt overnight. The racial tensions, the economic struggles of the Asians and Blacks, the dislike of the Blacks and Asians of each other, and the endless robberies, murder, assaults, auto thefts and burglaries created a fearful and resentful atmosphere. The mood was exacerbated by lack of city response and police insensitivity.

Observing the fires of rage fueled by the police acquittals and biased media that lasted six horrific days, K.W. Lee questions not why the violence happens but when the next one will flare up.

Edward T. Chang, a professor at University of California who, in an activist role, worked on racial reconciliation in the immediate aftermath of Sa-I-Gu, examines Korean American identity. He looks at how Korean and other Asian immigrants moved to poorer sections of LA, never losing their cultural identity, and nearly isolating themselves from the greater American culture and language. Chang criticizes the mainstream media at that time for its racial bias and cultural ignorance. The Asian community would suffer many unnecessary hardships of their self-isolation before demanding equal rights in their new and necessary identity as Korean Americans.

In a section on American Toxicity, Darnell Hunt explores American racial intolerance by describing how police and vigilantes racially profiled immigrants. Hate crimes toward Asians soared during COVID-19 pandemic. Hunt suggests that there has been systematic exploitation of white political and economic anxieties, and that immigrants have been blamed.

In the section on Roots, Riots and Reflections, civil rights attorney and longtime Koreatown resident Do Kim examines the common roots of Blacks and Asians in their racial profiling and their common need for representation in the greater society. As Do Kim remarks, it took three decades to heal the damage. The city, the communities of color, and solidarity movements of immigrants for rights and representation have all contributed to the ongoing healing. The city’s past is also a shared event, not to be forgotten or repeated.

In the section on Journalists Writing “Truth to Power,” Dexter H. Kim, journalist, filmmaker and website editor, comments how the events of April 29, 1992 still “elicit pain, anger, and sadness” among the people who remember and witnessed it. He brings up May 2, 1992, a day of commemoration when some 30,000 people assembled at Ardmore Park (currently Seoul International Park in K-Town) to call for peace among the people of Koreatown. It was a symbolic act for Asian Americans to gather and call for a new solidarity in order to be wiser, more aware, and ready to rebuild their community.

Kim points out that Korean immigrants were known for buying cheap property and doing business without understanding the class structures and economics of the community at large, which led to resentment and misunderstanding among non-Koreans in the community. Staying in a Korean cultural/language environment in the U.S. and crying foul when the American Dream is still unattainable is not the system’s fault, he argues. A key role for younger Korean Americans is to understand cultural disparities and racial disenfranchisement better, both for their own ethnic communities, and for other marginalized communities.

In A Daughter of Koreatown, writer Sophia K. Kim recalls the past and present of LA, from the perspective of Korean immigrants. Los Angeles Koreatown was once a poor neighborhood of Blacks and recent Asian immigrants. She discusses social disenfranchisement as a shared experience of Blacks and Asians. She also points out that tightness of a group creates an exclusive, closed attitude. In general, Asians and Blacks held negative, stereotypical images of the other, creating not mutuality but mistrust and caution.

How one journalist brought out the voice of Koreatown

The work of K.W. Lee, known as the “godfather of Korean American journalism” because of his leadership during Sa I Gu and his mentorship of young Asian American journalists for many years, is honored in this collection. His writings during the events of those times show how he witnessed the violence and then became a catalyst in the work of racial reconciliation. He had a reputation for taking firm stands on civil rights, having an unwavering belief in justice, and for making blunt remarks in his writings (and in person) about racism, inequities, and media bias.

Reporter Soojin Kim profiles K.W. Lee’s life. She tells the story of how he grew up in Japanese-occupied Korea, and was a soldier in the Japanese army. After immigrating to the U.S., ostensibly for a college education, he stayed on and had several reporting jobs in the “Jim Crow South” during the years before the civil rights era of the 1960s. He pursued many stories of about Blacks in the rural south.

After moving to California, he spent decades pounding the streets as an enterprising beat reporter in Sacramento and Los Angeles. Lee started a second career as an editor, founding two English language newspapers covering the Koreatown beat. This new direction started with his coverage of the Chol Soo Lee false conviction story, which he followed with fierce conviction as a reporter for the Sacramento Union.

After retirement, Lee became a spokesman and activist, and continued to plead with the culturally-competent and bi-lingual second generation to speak up for the rights and representation of their first-generation elders.

Moving on, with caution

Since the 1992 LA Riots, the racial, economic and cultural issues have subsided, along with a new generation of more aware Blacks, Koreans, and Latins. The city operates with political caution, though an undercurrent of resistance and mistrust are still there.

In recent years, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated new anti-Asian hate when rumors that the disease originated from China ran wild in the media. Random shootings of Blacks by whites and/or by police have escalated new fears. The 2020 George Floyd murder in Minneapolis became the new poster of racism and police brutality for the nation, arguably for the world, harkening back to the Rodney King incident in 1991.

This book is excellent as a reexamination of a key time and place. The writings, retrospective and reflective, seem sensitive after 30 years. Not all writers are forgiving of those racially-tense days. The blame game and depiction of Koreans and Blacks as victims of white brutality is an over-simplification of the complex social milieu that is Los Angeles. The sentiments of racial tensions are still there, as are the economic and political issues at the root of those tensions.

Each of the writers reflect on the lessons of those times, and what can be done for future civil stability. Civil unrest in any city or country occurs as a reaction to the insensitivity of the state or people. People’s movements and attention by media counter lack of progress by police and other government bureaucracy.

A section on Reflections and Resources includes a detailed timeline of events before, during and after the April 1992 riots. There are final comments, including how, in the 30 years since the events, the Koreatown of that time has been rebuilt. New generations of Korean and Asian Americans, African Americans and others live in a multiracial environment.

However, the transnational city of Los Angeles struggles to deal with many issues of justice and social welfare, among them continuing rampant gentrification and escalating residential prices, related homelessness and economic disparities.

A new kind of misery has been recently visited upon Los Angeles and other big cities in the form of the rounding up and kidnapping people of color, assumed unjustly to be undocumented immigrants. Los Angeles residents are unlikely to put up with this kind of disruption and injustice long term before more widespread resistance breaks out.

We Americans have long experience with and recognize the causes of social tension and the actions needed to resolve them. Many of the writings point out how the LA civil unrest and the healing afterwards exemplify how reform must come from the very people that need it, through the solidarity of protests, legal channels, the sway of the media, and persistent efforts towards social change.

This unique collection is a description of a time and place, but includes many reflective articles on how the LA civil unrest can inform ongoing struggles of marginalized communities. The fact that it happened 30 years ago means that the reader can reflect on the long-term impact of this seminal event on the Korean American community and other ethnic communities today.