Standing for Black and Asian lives in Minnesota, two women find a partner in the battle | By Sarah Han and Kat Porter (spring 2021 issue)

Sarah Han: May 25, 2020

Four months into a global pandemic, the world had shut down. Violence towards Asian people had increased exponentially due to the racist tone of the Trump administration. I watched a Black man die underneath a white policeman’s knee. It lasted eight minutes and 46 seconds. Not only did I see the life drain from the eyes of George Floyd, but I joined my hometown as a spectator to the racism that had always been there. I witnessed destruction worthy of the start of an apocalypse. To be completely transparent, I could not connect the senseless killing of this man to my experience.

Although I didn’t understand where I belonged in this, something drew me to join the protesters to support Black Lives Matter. I marched with my sign. I taught the kids at my school the importance of this movement. I called out to my white friends on social media to do more. I did everything my white-adjacent person knew how to do. As time went by and I watched the destruction of my city, my fear mounted.

Kat Porter: May 25, 2020

I was off work that day. I had recently joined TikTok as a form of solace from the isolation of the pandemic. I received a phone call from my 25-year- old son regarding a Black man’s death at the hands of the police. It happened two blocks from where I raised two of the five of my children, in the Bancroft neighborhood of South Minneapolis. Not long after, I had watched many videos of this Black man’s death that happened in front of the store we had often frequented for essentials. He could have been my brother.

It sucked the life out of me when I saw, on TikTok, a Black man being pinned to the pavement by his neck. It was the same pavement on which my children and I had often stood, waiting to conduct the activities of our lives. George Floyd’s life leaving his body under Derek Chauvin’s knee tapped into the trauma of Alton Sterling saying repeatedly, “I can’t breathe” just a day before Philando Castile lay bleeding in front of his girlfriend and her child.

Sarah: May 30, 2020

My wife left me. A white woman walked out the door and out of a Korean adoptee’s life forever. I was left alone in a quarantine while the National Guard took over our cities. Fearing for my own safety, I locked all my windows and doors without hesitation. I downloaded a police scanner app to monitor if anything was happening in my neighborhood. I was left to fend for myself. The re-traumatization of the abandonment caused me to shut down.

I adjusted to the new reality of my existence. I questioned everyone and everything. I couldn’t trust anyone. The faith I had in love and in the good of people was gone. The hundreds of people dying from COVID-19, the ruin of the Twin Cities, and the ending of my marriage became too much. Everything I knew no longer existed.

Kat: May 31, 2020

Nothing about my world was the same. I woke up and observed that the free spirit of Pride Month in Loring Park had disappeared. Instead of rainbow flags, the drab camouflage of the National Guard replaced the colorful garments of the drag queens at the festivities. Windows were boarded up, a reaction to the unrest that had come to the Loring Park neighborhood of downtown Minneapolis. I took refuge in the closet of the 12th floor apartment where I worked and lived, fearing that white nationalists would blow up the gas station behind my building. The only thing that brought me a sliver of comfort was making facemasks for loved ones.

My job put me at the front desk of a luxury residence, protecting white people, while Black, indigenous and people of color (BIPOC) bodies were out there protecting my people. That was the afternoon that a semi-truck barreled into a sea of people while they demonstrated for racial justice on Highway I-35W. The finality of what I needed to do became clear. I sought help for my trauma, which led me to stop making excuses for my complacency. I had to fight.

Kat: November 6, 2020

After three days of waiting for the election results, a collective exhale was heard throughout the nation when Kamala A. Harris was named the first Black/Asian female vice-president of the U.S.

Sarah: November 6, 2020

I had hope again. One of my people was in office. Perhaps we could move away from the white supremacy that kills and hurts Black and brown people every day.

Kat: November 6, 2020

I cried for two hours while I kept checking social media and made sure that my pink and green pashmina was clean, my Converse were on point, and my hair was flat-ironed and ready to go.

Sarah: March 16, 2021

Six Asian women were shot dead near Atlanta by a 21-year-old white man. Authorities said the cause was a sex addiction and that the suspect was “having a bad day.” The fact of the matter is, I am Asian and although I didn’t grow up in my skin, I am in my skin. This was made very clear to me that day.

Already experienced in rallies and marches, I searched the internet for an Asian American event. Finding one in Levin Park, Minneapolis, I attended it with a strange sensation the whole time I was there. The speakers were talking about my people, our oppression, our history. We chanted, “Asian Lives Matter.” I saw many white men walking around and my thought was they were there to objectify and fetishize our women. My photo was taken by several photographers, an Asian woman with almond eyes brimming above her facemask, holding a sign that read “Say their names.”

When I got home, I processed this experience, and for the first time in my life I accepted the skin in which I was born. Things changed after that. A level of fear and anxiety entered my body and became significantly worse when I stepped foot out of my house. I was afraid to walk my dog. I was afraid to get groceries. I had a rational fear that someone driving would see me and run me down with their car. The thought of wearing sunglasses to hide my Korean eyes actually crossed my mind.

The next day I had received a message from a Black woman I matched with on a dating app.

“How are you?”

“A little crazed from the whole Atlanta thing yesterday. How are you?”

“I’m feeling a little heavy, if I may be honest. This world is not a cool place right now! Are you okay?” My own parents didn’t reach out and ask how I was. This complete stranger who had survived years of her own injustice and violence showed concern for me. Little did I know that this was the beginning of something special.

Kat: March 16, 2021

I was exhausted. When I heard about the Asian women near Atlanta, it was the same violence I had witnessed in my own community. Another murdering white man who, after committing such violence, was still granted a level of humanity and decency by police, although his crazy act had just cost many BIPOC women’s lives. I was tired of trying to explain what mattered in my world. Being a Black woman in a sea of BIPOC folks, buried under white people, I just wanted to reach out to make sure my sisters were held up.

I saw somebody with whom I thought I could share a connection.

Social justice. Check.

Wanting better for our communities. Check.

Not being seen as an object or fetish. Check.

Validated for who we are. Check.

She wanted the same quality of life that I sought, and she was a woman wanting love, regardless of race, gender, class or beliefs. Most of all, I saw her as a human being. That may be generic, but over the past four years, dealing with the previous U.S. administration, it was easy to close myself off to others. I think my closed-down thinking also came from the reality of being a Black woman in a world where Black and brown ideas of beauty seem so devalued.

Kat: April 16, 2021

The violence against Black people never stopped. A week before the Derek Chauvin verdict, a Black man was killed by a white policewoman during a traffic stop. We went to peacefully hold space in front of the Brooklyn Center police department. Thirty minutes after we arrived, the police announced that demonstrators had to disperse. I looked at Sarah and said, “we need to leave or else we will be arrested.”

We headed to the car which was half a block away when we spotted a line of law enforcement coming towards us. Given my experience with the authorities during protests and the violence that they are capable of, we had no other option than to run.

We turned to head in another direction and were met with another line of police. It quickly became chaotic, with people running every which way, jumping in their cars and dodging the men with the batons. When we realized there was no possibility of a safe exit, Sarah showed physical distress and I was done running. A military vehicle pulled in front of us as 100 suited-up men screamed at us to get on the ground and put our hands up. We complied. Alongside hundreds of others, our hands were zip-tied behind our backs and then were escorted to police vehicles. Our identification was recorded, pictures taken, and we were put on a heavily-guarded prison bus.

Sarah: April 16, 2021, 10:30 p.m.

I thought I was going to vomit sitting in the back of the cop car. Adrenaline pulsed through me with the fear for Kat’s and my own safety as women of color. They ripped me out of the car and put me on the bus. I sat there with 20 other arrestees, and prayed that Kat was okay.

Kat: 10:30 p.m.

I knew the drill. Stay calm. Don’t be flippant. Observe. Much like I’ve done in the past. I could tell by Sarah’s face that she didn’t understand what was happening. It was more important to observe everything that was going on, versus demanding that I be treated fairly. I wanted to know what my arresting officer looked like, the tone of his voice, any remarkable features or anything out of the ordinary that I would need to report later if I was mistreated

Sarah: 11 p.m.

The door to the bus opened and she was there. I moved to sit near Kat and we quietly discussed what might happen. She was calm, cool, and collected. I was not. The prison bus left Brooklyn Center around 11:45, and headed towards downtown Minneapolis to the Hennepin County jail.

Kat: 11:45 p.m.

I checked out (emotionally) by the time the bus drove underground to the jail entrance. My only hope was that I would make it out… alive. The processing began, and they put me on the men’s side. Sarah went to the women’s side. I was alone throughout the booking process. Sarah had support from about 10 other women who were arrested. I complied with everything, but I was treated like an animal.

Sarah: April 17, 2021: 1 a.m.

I had to disassociate. If I allowed my emotions to attend this experience then I would have had a panic attack. I somehow survived the four-hour booking process, the body search, the mugshot, the constant questions, the medical check and the sitting in the dirty, tiny holding cells. At 4 a.m. they walked us up to Block B on the fourth floor.

Kat: 1:30 a.m.

I unrolled the itchy wool blanket. I looked around my cell and saw a disgusting toilet and sink. There were drawings on the wall, bodily fluid stains and other unknown stains. I sat on my bottom bunk and held onto the blankets. The bright fluorescent lights dimmed and I noticed that one of the drawings was dated April 27, 2012. I was sick. I didn’t hear anyone else come into the area. I resisted sleep.

Sarah: 4:30 a.m.

I laid on my bunk afraid of the quiet. My cell had a drawing on the wall of a potted cactus flowering. I am pretty sure it was drawn with feces. I didn’t sleep. I couldn’t sleep. I worried about Kat.

Kat: 7:30 a.m.

The lights came back on and breakfast was delivered, consisting of milk, juice, and cereal bars. An hour later a guard opened our door and said we had an hour to walk around the common area. I walked across the room, and through a slatted window I saw Sarah’s tattooed arm. I approached her cell and we talked through the slot in the door.

Sarah: 7:30 a.m.

Seeing Kat’s face through the window after not knowing where they had taken her made my heart skip a beat. She was unharmed, that was all I cared about.

Kat: 1:30 p.m.

A guard banged on my door and said, “Porter, roll up your bed and go through that door.”

Sarah: 1:30 p.m.

I was on the phone making a collect call when I saw a guard tell Kat to get her stuff and exit the block. I hung up and she approached me and said she was being released. We were both released and breathing fresh air by 2:34 p.m. Right after that, we discovered that my car had been towed. It cost $300 to get it out of the impound lot. I had numbness and pain in my left hand, and later found out I had suffered nerve damage from the zip-ties being too tight. Another $250 for a doctor visit. Peaceful protesting costs a lot.

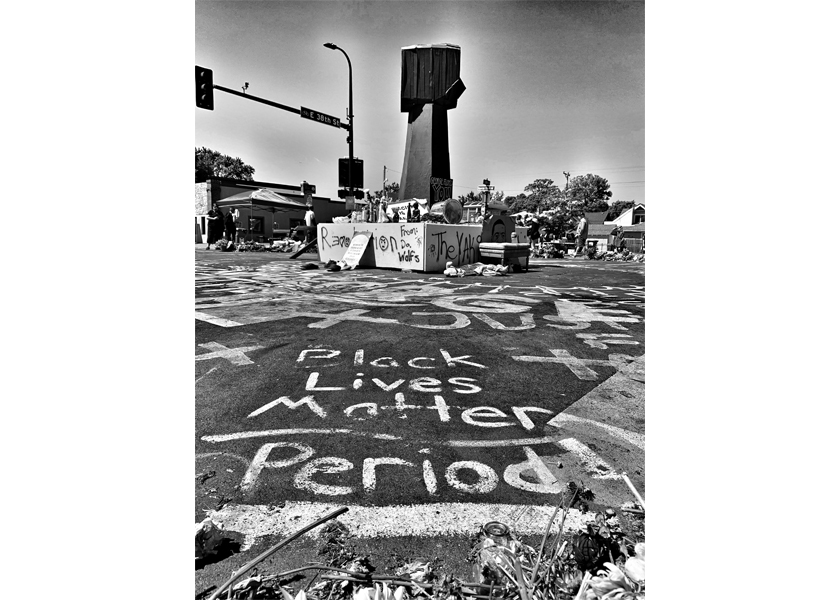

Kat and Sarah: April 18, 2021

We travelled to George Floyd Square to attend a celebration honoring the historic connection between Black and Asian communities. Standing side by side in a sea of white people, feeling distrustful, given the past 24 hours, all we had was each other. This experience that we weathered through together as a Black woman and a Korean woman secured the need to continue to fight for both races despite the white supremist wedge. For Kat, embracing the Asian folks in her life allows her to understand the commonalities that exist, but she doesn’t take for granted the path that her Asian sisters have to walk. We build each other up. We put our heads and hearts together, and through that, we find respect. When we stand alone, Kat sees 180 degrees, Sarah sees 180 degrees. But when we hug one another, Sarah sees Kat’s back and Kat sees Sarah’s back.