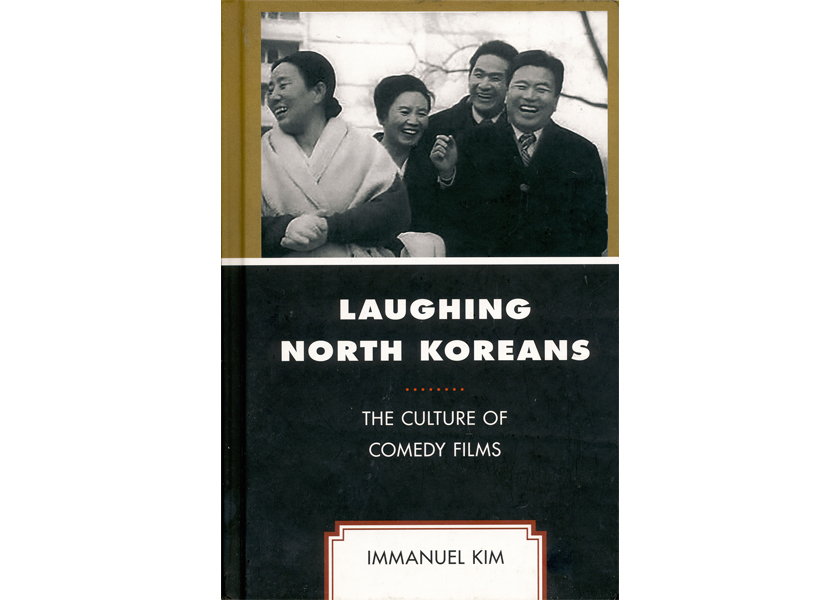

Laughing North Koreans: The Culture of Comedy Films ~ By Immanuel Kim

(Rowman and Littlefield Press, Lanham (MD), 2020, ISBN #978-1-7936-0829-1)

Review by Bill Drucker (Fall 2020 issue)

North Korean specialist Immanuel Kim explores the historical and cultural aspects of North Korean films, particularly comedies, in this recently published study. Kim shows, through the message of its films, that the hermit kingdom does not function in a domestic or international vacuum. The 25 million North Koreans do indeed view domestic films, watch TV, and even see South Korean and foreign films and shows. Films are a soft engine of cultural change, particularly in North Korea, which has been focused on not being vulnerable to South Korean or western influence.

The development of the North Korean film industry was controlled by the nation’s small dynasty of three leaders, and has been influenced by Communist Russia. First leader Il Sung Kim used film as a social vehicle for state propaganda and a means of controlling and educating masses. Second leader Jong Il Kim, who loved western films, saw film primarily as a means of entertainment, but also used it to maintain the official ideology.

The second Kim also wanted to use film as a means to gain international recognition for the country. That wish was never realized, but Jong Il had a heavy influence on North Korean film content and format. The current leader Jong Un Kim does not seem to have much interest in film as a state tool, though he has acknowledged the North Korean films of note and awarded well-known actors for their contributions.

Author Kim believes that North Korean comedies can provide insights into North Korean modern society, marriage and dating, familial constructs, and human interactions. The state ideology, as it emerges in comedies, is softer and less direct than most ideological material. For example, while North Korea officially espouses a classless society, its comedies strongly express Confucian values, such as the dominance of the male hierarchy and the existence of many traditional family obligations. The films tend to show the father in a classic role as head of the family and clan. This mirrors the role of the state leader Kim as the “father” to his people.

The book explores comedy film history from the early ‘60s to the present. While North Korean films rarely are screened outside the country’s borders, author Kim shows that the state produces new dramas and comedies on a yearly basis. According to the author, comedy films actually “challenges, subverts, and, at times, reinforces the dominant political ideology.” North Korean filmmakers in the comedy genre are walking a fine line. If the patriarch is too much of a clown or fool, it reflects poorly on the authority figures the characters are supposed to mirror. Should a character of a son or daughter rebel, the plot line can be viewed as a message of open rebellion against the state.

Western film critics and the author see the North Korean comedy genre overall as comedy of manners. Family obligations, domestic responsibilities, and social rules are depicted in the characters’ gestures and speech. Family members may be overly rigid in their social behavior and come off as ridiculous. In North Korean comedies, there is no western comic fool that generates humor with physical comedy, the classic bull in the china shop. The North Korean funny character is a more serious fool, who “tries to do everything correctly and believes that everything is under control,” Kim explains. Chaos ensues despite and because of the very earnest intentions of the character.

This study is excellent at analyzing why the comedic film is reflection of society. The most famous North Korean comic actor is Se-yong Kim. Two films of note are Our Meaningful Life (1979) and I Will Play the Drums (1977) that celebrate the comic actor and is devoid of any heavy ideological message.

The author also looks at the spy genre in the parody Boasting Too Much. Starring Se-yong Kim in a slightly different type of role, the film spoofs the world of spies and national security. There is no suave James Bond character, no fancy gadgets or sexy girls. Just a bumbling worker caught up in the frantic paranoia of spies threatening to destroy the social fabric of the beloved state. This is a fascinating subject for comedy, since North Korea takes security very seriously.

There is also a sub-genre of family foibles, typified by the popular and long-running series, My Family’s Problems, which spanned 1973 to 1988. It built careers for the actors, writers, producers, and directors. As popular as the series was, it received negative reviews from domestic film critics, censors, and even Jong Il Kim, who stated that the topics of the film series were not ideological enough. The production quickly placated the leader with some ideological messages.

A comedy of manners is the style of the film Day at the Amusement Park (1978). Mistaken identities and confusion ensue as two couples meet at the park to arrange a marriage between their children. One notable feature is the actual Mount Taesong Amusement Park, located 12 miles outside Pyongyang. The park was the state’s offering to its people, a place for fun, relaxation, and escape from the city. The actual location is also historic, since the backdrop of mountains and foothills was as natural fortification for the ancient capital of Koguryo in the first century.

Love and marriage are fodder for comic situations in any society, and North Korea has quite a collection of them, including O Youth, Urban Girl Comes to Marry, On the Green Carpet, and Our Fragrance. The lovers are portrayed in line with state ideals, but there is also a Hollywood-style treatment of the characters as somewhat glamorous. The male is the epitome of masculinity, loyalty, and high morals. He is a dreamy image for the females of the audience. The woman lead is pretty, well versed and obedient, the ideal candidate for wife and daughter-in-law. This image also aligns with state, Confucian, and male-centric ideals.

Of note in Our Fragrance, the young woman is first shown wearing attractive western attire, then in following scenes, she wears a traditional hanbok. One can speculate this is an ideological message that she finds happiness in things Korean, not western.

In a more recent film project Comrade Kim Goes Flying (2012), there was a rare collaboration between North Korea and Belgium. In it, a humble coal miner Yong-mi dreams of being a world-class trapeze artist. Undaunted by her failed audition, she trains hard and falls in love with her trapeze partner Chang-pil. The film’s popularity was what leader Jong Il Kim hoped for; outside recognition and cinematic cooperation. The themes and storyline are pure state ideology: Follow your dream, work hard, do not be discouraged, success will be yours, and you will make the state proud.

North Korean comedy, like many art forms of North Korea, is an art form unto itself. None of North Korean’s leaders, not even the film freak Jong Un Kim, wanted to appropriate western comedy styles and standards. So to compare the notable award-winning comic actor Se-yong Kim to, say, Charlie Chaplin is a stretch.

Nothing remains static, not even in North Korea. As outside cultural influences persistently seep into the culture, there are hints that subversive elements for social change under the guise of comedy could make that change a reality.