Adoptee Kara Bos won a paternity suit in South Korea: What’s next? | By Martha Vickery (Summer 2020 issue)

A first-ever paternity lawsuit in South Korea by Korean American adoptee Kara Bos in June was a success, in that she won the case. Whether it will be personally successful for the young woman who poured money, time and energy into her quest over more than three years is still to be determined.

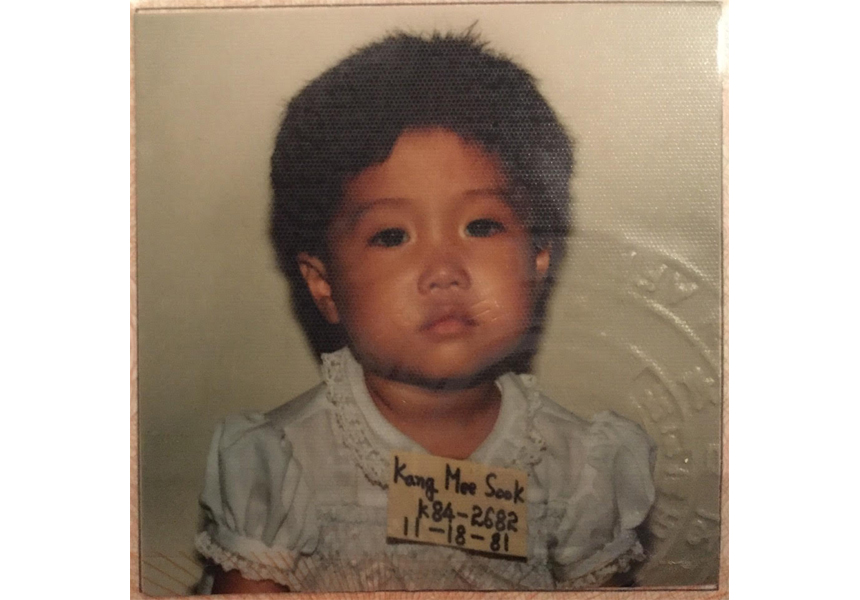

At this writing, Bos’s birth family on her father’s side are still refusing to talk to her. Her birth mother’s name and whereabouts are still unknown, but because of the media attention the case has drawn, a reporter from the South Korean TV network MBC is on the trail. Bos knows her original Korean name and birth place, and knows MBC is searching for “all the Kang, Mi Sooks from Goesan,” she said. Beyond that, she does not know what the investigation will include.

Bos, who grew up in Michigan, and now lives in Amsterdam with her two children and Dutch husband. She moved to Amsterdam in 2016, and, inspired by the bond she formed with her own daughter, began her birth search journey in earnest in 2017. She returned to Korea, saw her foster mother, and distributed leaflets in the market where her records said she was found. It was 2018 when she got DNA tested, and after uploading to a larger data base, the sample got a match of someone in Korea.

The match turned out to be a nephew on her birth father’s side (son of an older half-sister). The nephew was living at Oxford University (in England). The two developed a relationship of two friends. They even spent some time getting to know one another in London and Amsterdam. The nephew did not anticipate that the elders in his family would refuse to help, but that is what eventually happened. No one, except for a cousin of her nephew, who had studied in the U.K., would even have a conversation with her.

The elder family members rejected her, and were angry that she even approached them. They expected Bos to go away. Instead, she pushed back.

Bos followed up on many clues, which culminated in a successful lawsuit to force a man she had never met to recognize her legally as his own child. It was officially decided in June. She had to get a DNA test in March at Seoul National University. She returned to Seoul in June, and was granted an exemption from the 14-day quarantine law through some connections in the embassy in The Hague. Her birth father was required by the court to get a test by the same Seoul National University lab.

The day she got the news that his DNA showed he is undoubtedly her birth father was a good day. “I felt completely vindicated,” she said, after months of hearing that her birth family was shocked and angry about her accusations. “They had been characterizing me as a crazy con-artist,” she said. Having those results made all the work and stress worthwhile.

The first newspaper to do a story was the Manilla Times, Bos said, because the reporter wanted to follow up on previous successful paternity suit by a Filipina woman with two children against a Korean man. The Seoul bureau chief of the New York Times wrote two articles about Bos’s quest and successful lawsuit. Thereafter, other media jumped on the story. When Bos returned for the trial and promised meeting with her birth father, she did two or three interviews per day for many days, trying to draw as much attention to the case as possible.

Bos said that when she was investigating the practicality of doing a lawsuit, the lawyer she used, and other lawyers she asked, were in agreement that prosecuting a paternity lawsuit against the man she presumed to be her father, based on a lot of solid evidence, would be “easy.” It took an outlay of cash, about $5,500, which was a lot of money for Bos, but the procedure was fairly straightforward and there was little doubt it would be successful.

What she could not do, she said, was force her father to have a relationship with her, or even talk to her. She negotiated a meeting by telling her birth family she would keep the family’s details confidential from the media if they did meet with her and cooperate.

On the appointed day of their meeting, he showed up in a hat and sunglasses, with two body guards. At the time, she was horrified, but now she jokes that she felt like she was in her own Korean drama. She tried to give him a letter she had written. He refused it. She and her attorney talked, he listened, often interrupting with denials. “Saying I was disappointed is an understatement,” she said. The meeting lasted all of 10 minutes.

She is looking at her successful lawsuit as a precedent-setting event for fellow Korean adoptees, something that will help other adoptees in years to come, particularly those with no other recourse to birth family except for DNA. In an interview with Adapted Podcast by Minnesota Korean adoptee (and TV reporter) Kaomi Goetz, to an online audience of mainly Korean adoptees, Bos explained how she looks at how this legal tool can change the paradigm for searching adoptees:

In Korean society, if adoption never would have happened, and we all stayed in Korea …then Koreans would have had to accept biracial children, and all the scandals that resulted from affairs. Korean society would have had to accept and create measures socially to change this thought process. But because that has never been done, because there was always an easy way out, in sending kids away for adoption, and also because adoption always looked at adoption from the parents point of view. and never looked at it from the point of view of the child who becomes an adult, and …what are their rights then?

Since coming back from the June trial verdict and the meeting with her birth father June 15, (she missed the trial which occurred May 29, but some Korean adoptees went to the trial to observe), Bos has been waiting for word from the MBC Network on whether they have information about her birth mother, but here has been no news so far.

Bos realizes that using media for something as sensitive as finding a family member is a two-edged sword. It can work well during the searching stage, because a lot of people hear the information. But whether it will work well for a reunion is a different matter.

“Obviously, if there is a reunion, they will want to film it, because everyone wants a happy ending, right?” she said. “Even if that happens, I don’t want it portrayed in that fashion. I want the recognition of the pain and the story of why it was so difficult. The fact that it happened only because it had this kind of media attention, and only because I filed a lawsuit. That’s why I was able to even find her.

“So, the story line needs to have more than a glorious reunion where everyone’s happy ever after,” Bos reflected. “And a reunion does not mean that everything is happy and lucky. There’s a lot of shame involved. There’s a lot of guilt. There’s language and culture and all kinds of issues involved with it. That raw side of it needs to be recognized.”