Cuckoo explores modern loneliness and role of technology | By Joanne Rhim Lee (Winter 2024)

Cuckoo, written and performed by Jaha Koo, February 6-8, 2025 ~ McGuire Theater, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis

In 1997, South Korea was rocked by a catastrophic financial crisis which affected millions of its citizens, including longtime employees of corporate conglomerates (chaebols). There were immediate layoffs, and salaried workers and their families abruptly lost their financial security and status. In the years following the crisis, South Koreans worked hard to recover, but the emotional scars often remained, even after the economy grew and South Korea became a global powerhouse in manufacturing and technology.

Jaha Koo was a middle schooler at the time, and remembers the stress and anxiety that surrounded his family and his community. One of his friends even committed suicide, which shocked Koo to his core. Later, unlike many of his peers who felt pressured to pursue steady careers in science and technology, he chose to study theater and music in college and later moved to Europe to continue his studies in the performing arts.

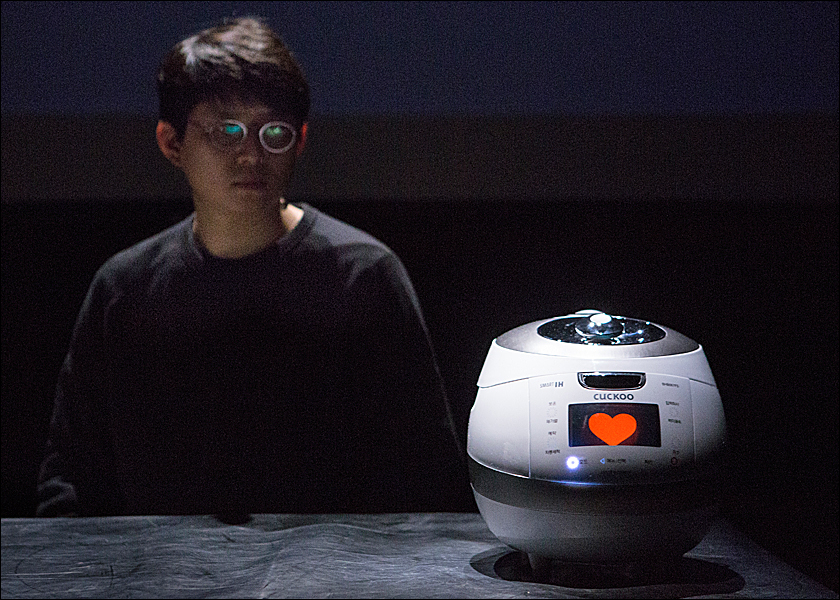

In 2017, he produced Cuckoo, a unique multimedia performance that highlights three talking rice cookers. Since then, he has performed it at various theaters and festivals all over the world. His recent performance was at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis from February 6 through 8. Cuckoo was part of a series of four plays, spanning January and February, in Out There, an annual Walker celebration of experimental plays and storytelling offered every winter.

Cuckoo is the brand name of a high-end rice cooker, a ubiquitous kitchen appliance in virtually every Asian household. It announces when the rice is done in a warm sing-song voice in Korean, like a helpful robot that you might want to be your friend.

Koo begins his show with a series of projected images on a large screen, with a narration about the financial crisis, and then announces a very important event in 1989 — his own birth. It’s an indication that this will not only be a serious diatribe about collective trauma in Korea, but a humorous running commentary as well.

The three rice cookers begin speaking to each other, first in a very basic instructional way, with their glowing lights indicating which one is speaking. But soon it becomes clear that Koo has managed to hack into their electronic code, unlocking their different personalities that can be quite competitive, funny, and sad.

Koo does not want to cede the spotlight completely to the rice cookers, and later climbs up on the table and joins their conversation. He asks many deep questions about the role of technology in society, but like a good writer and artist, does not provide easy answers. Instead, his audience is left pondering what exactly happened in Korea that has led to so much loneliness and isolation, and how can we study the past so as to avoid the same mistakes in the future.

A cuckoo world, diaspora style: Multi-disciplinary artist Jaha Koo discusses global Koreaness with Korean Minnesotans at the Walker | By Jennifer Arndt-Johns

A meet-and-greet that invited in the local Korean community was a welcome but infrequent opportunity for visiting multi-disciplinary artist Jaha Koo, who presented his experimental work Cuckoo at the Walker Art Museum in February. It was also unique for the guests, who talked to the artist about his work’s themes of modern South Korean life, and how Korean communities try to preserve aspects of their culture wherever they live.

Koo, who is based in Europe, integrates music, video and performance for his play, which includes three technologically-hacked rice cookers (named Hana, Duri and Seri, meaning first, second and third). His experimental performance was included in the four-play series Out There presented at the Walker Art Museum.

The reception was intended to welcome the artist to Minneapolis, and provided Korean community leaders a chance to connect with and learn more about Koo and his team in advance of the performance.

I learned that while Koo, as a part of his artistic process, tries to connect with Korean communities wherever he travels, he told the group that it was the first time that his performance hosts had organized a community meet-and-greet.

The reception was held in the green room off the McGuire Theater, where Cuckoo was staged. Koo was with his wife and collaborator Eunkyung Jeong, his producer from CAMPO Arts Centre in Ghent (Belgium) Marijka Vandersmissen, and Technical Director Bart Huybrechts for the February 4 event.

Representatives from the local community included members from the Korean Institute of Minnesota, Theater Mu, Jangmi Arts, and the Korean Cultural Association. The Walker was represented by Senior Curator Philip Bither, Senior Program Officer Julie Voight, and Project Manager for Performing Arts Sherisa Oie.

Light refreshments were served, and to the delight of Koo and Jeong, there were some yakgwa (Korean traditional cookies), honey oranda snack bars and roasted seaweed, along with fruit, cheese, crackers and charcuterie. I pointed out that the yakgwa and honey oranda snack bars were carried temporarily by Costco because of Asian Lunar New Year, to which Koo lightheartedly replied “We love Korean food propaganda.”

As the group settled into a circle, the conversation transitioned into spontaneous dialogue, providing the artist and his team with a laundry list of places to visit in the Twin Cities, including a discussion of the guests’ special request for Korean soup.

Koo shared the most interesting food-related experience that emerged out of his recent trip to present Cuckoo in San Paulo, Brazil. He said that in San Paolo, the kimchi retained the flavor of what he called an “old Korea taste,” something he thinks is fast disappearing through modernization.

The Korean Brazilian population in Brazil is estimated at 50,000, the most significant population in Latin America. Koo said he learned that the first Korean immigrants to arrive in Brazil were fleeing the Japanese occupation. In 1962, after diplomatic negotiations led by organizations and former anti-communist political prisoners with interests in helping the Koreans relocate, South Korea and Brazil agreed to allow immigration of workers from South Korea’s agricultural sector to Brazil.

I had a similar experience feeling that the “old Korea taste” as well as old Korean values are becoming scarcer when, last year, I was trying to identify instructors to help teach Korean cooking classes at Korean Institute of Minnesota. I met with a member of a church-based women’s leadership group to identify some candidates. I was surprised that she laughed when asked about people willing to teach kimchi-making, saying “None of us know how to make kimchi. We buy it at the grocery store!”

She suggested I talk to some of the “older elders,” as some still made their own kimchi. She also chided herself, adding that individuals in “your” community (referring to the adopted Korean community) probably have a different appreciation for learning about Korean cuisine because they weren’t raised with it.

Koo’s comment resonated with me with some sadness I often feel about generational loss of cultural knowledge. How will the traditions and traditional Korean food sustain and maintain its authenticity through time if no one teaches it, nor has the desire to learn it? Koo’s palate was attuned how the Korean Brazilian community had preserved some of the old flavors. The skill and sensitivity of that community in passing those flavors to the next generation is a reminder of why food is culturally important, not just for the food’s sake, but also as a form of self-preservation. As he described, food is an “asset to my own identity.”

The group also shared stories about cultural idiosyncrasies that they experienced, observed and wondered about in recent times. One topic addressed was the export, proliferation and visibility of Korean entertainment, also known as the Korean Wave, or Hallyu. Koo mentioned that in recent years in Ghent (Belgium), instead of hearing “ching-chong chants” when encountering young children, he and his wife have been greeted by their attempts to speak Korean, or have even received an impromptu serenade in the form of a K-pop song; an example of the power of cultural exports to transform attitudes.

On a local level, Koo and his team were surprised to learn about the adopted Korean population in Minnesota, of which they had no previous knowledge. After the last performance of Cuckoo, I briefly spoke to Cuckoo producer Marijka Vandersmissen. She told me that the most poignant and thought-provoking comments Koo had received about the performance were from adopted Koreans. Many said they deeply identified with the term golibmuwon which Koo explains as “untranslatable” in Korean but describing “a form of helpless isolation.” The feeling, he explains in the Cuckoo narrative, is deeply entrenched in his generation of South Koreans.

Prior to seeing Cuckoo, the term golibmuwon was an unfamiliar Korean term for me. Yet, I can understand how such a sentiment would resonate with the community of adopted Koreans culturally isolated from their places of origin. I also wondered about the distinction between golibmuwon and the uniquely Korean emotion known as han.

While the event had some thought-provoking moments, one that still remains with me is Koo’s explanation of the state of feeling as if one does not belong anywhere. He even remarked “I don’t know where I can die.” As I have gotten older, I too, have wondered about this question also. It’s a deep wondering and longing connected to one’s basic need of finding a true place of belonging.

Before receiving the invitation from the Walker, I had no previous awareness of Koo’s work. I am grateful for the opportunity to connect with Koo and his team, and the privilege of seeing his work performed on stage. I am hopeful that his other works, Haribo Kimchi and History of Korean Western Theatre can come to Minnesota so we may continue the process of exploring all the things we have in common.

Editor’s note: A Q and A interview published by the Walker Art Museum is at this link. Program notes for the performance are at this link.