100 years after Samil, descendants reap the legacy of Korea’s Independence Movement | By Doug Kim, Cho-lee Yeoul and the 100 Years Team (Winter 2019 issue)

The legacy of Mansei: 100 years on, March 1 marks the day independence emerged from a subjugated Korea | By Doug Kim

One century ago, Korea did not exist. If you searched for Korea on a map, you couldn’t find it. From 1910 to 1945, Korea was brutally subjugated by Japan. It’s hard to imagine today, as the hallyu wave washes the world over with K-pop, K-dramas, probiotic kimchi, and ubiquitous consumer goods, that Korea, now the 11th largest economy on the planet was once a colony —- occupied, exploited and abused for the benefit of Japan.

Korean Americans need to remember this nadir in Korea’s history, for it brings Korea’s character and modern achievements into sharp relief. Perhaps nothing in that 36 long years of occupation speaks more eloquently than the independence movement of Koreans that took place 100 years ago. This is also known as the Samil Movement (sam-il means three-one or March 1 in the Korean language), or the Mansei Demonstrations, because a Korean common cry for independence was “Mansei!” which means “May Korea live for 10,000 years!”

Understanding the Samil Movement requires some background. Any discussion must first recognize that Korea occupies a precarious strategic place in the world. It is an eternal buffer state, forever caught between larger powers. Korea has been fought over, invaded, overrun and occupied by the Mongols, Chinese, Japanese, Russians and NATO forces. An ancient Korean proverb sadly acknowledges, “When two whales fight, the shrimp’s back gets broken.”

Consequently, Koreans’ most foundational emotion is han. There is truly no English equivalent for this term. It encompasses anger, unrequited sorrow, resignation to an unfair fate, and quiet despair. Like dripping cave water forms stalactites, bitter experiences over millennia has solidified han in the Korean soul.

Understanding the Samil Movement also requires a review of Western imperialism in East Asia. China was forced to open its ports for trade by the British in 1842 (one of the British warships was the aptly-named HMS Nemesis). Japan was coerced into similar inequitable trade treaties and land concessions in 1853 by American Commodore Matthew Perry and his four “black” ships. Curiously, it was not a European or American that pressured Korea into westernizing. It was Japan.

This anomaly is even more remarkable in light of how quickly Japan nullified foreign incursion, and become an economic and military force in its own right. It took China 106 years (1843 through 1949, known in China as the “100 years of shame”) to throw off the yoke of foreign control and regain its sovereignty, but it took the small island nation only about 40 years. In 1894 Japan fought China over Korea, and after six months of consistent naval and land defeats China sued for peace in 1895. Less than a decade later, an increasingly confident and powerful Japan defeated Russia. The Russo-Japanese War (1904 to 1905) was also fought over Korea.

Having defeated the Russians and the Chinese, Japan was poised to take over Korea. This was not the first Japanese invasion/occupation of the “land of the morning calm.” Hideyoshi Toyotomi invaded Korea twice in the late 1500s. However, when Japan annexed Korea in 1910, it had the military and economic strength to secure and hold the peninsula. Korea, like many other formerly independent countries, was eventually forced into what the Japanese Empire euphemistically termed the “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.”

As a result of Perry’s 1853 “gunboat diplomacy,” the Japanese sent envoys to Europe and America to study technology, education and government. They learned how 13 small coastal colonies became a continental power, and admired America’s notion of “Manifest Destiny,” the belief that America’s duty and inevitable fate was to control the entire continent despite the presence of sovereign indigenous people’s nations within its borders. Japan’s leadership believed military/industrial build-up and conquest of her neighbors was Japan’s Manifest Destiny. Following the model of Great Britain, another island nation, Japan set about creating an economy and empire based on revenues from its colonies whose primary purpose was to provide material and manpower to benefit the island nation with its centralized government.

There were numerous political and diplomatic machinations engineered by Japan prior to the 1910 annexation of Korea, including the 1895 assassination of Queen Min, wife of the last Korean King Kojong, who opposed Japanese rule of Korea, and the Taft-Katsura agreement of 1905, which granted Japan control of Korea and the U.S. control of the Philippines.

Having annexed Korea, Japan set about exploiting Korea’s resources, enacting laws including:

— A 1911 measure that increased Japanese lumber companies’ access to Korean forests, and a similar measure in 1918 that transferred over four million hectares of forest to Japanese lumber companies. Excessive timber harvesting caused extensive erosion in many areas.

— A 1912 law that put Korean fisheries under Japanese control and enforced “joint sale” of all fish caught by Koreans. Eventually some 120,000 Japanese were competing for 200,000 Korean fishermen in the same fisheries territory.

— Another 1912 law that allowed Japanese to own Korean land. A large-scale resettlement program followed, and by 1918, 98,000 had settled in Korea. Displaced Korean farmers, left with no recourse, were often forced to work for the Japanese government.

Beyond usurping natural resources, the Japanese engaged in well-planned cultural genocide. F.A. McKenzie, a western journalist in Korea at the time, wrote:

It became more and more clear, however, that the aim of the Japanese was nothing else than the entire absorption of the country and the destruction of every trace of Korean nationality. One of the most influential Japanese in Korea put this quite frankly to me. “You must understand that I am not expressing official views,” he told me. “But if you ask me as an individual what is to be the outcome of our policy I can only see one end…. The Korean people will be absorbed in the Japanese. They will talk our language, live our life, and be an integral part of us…. We will teach them our language, establish our institutions and make them one with us.” That is the benevolent Japanese plan; the cruder idea, more commonly entertained, is to absorb the Korean lands…

McKenzie documented that Japanese regarded Koreans beneath contempt: “The Japanese believes that the Korean is on a wholly different level to himself, a coward, a weakling, and a poltroon. He despises him, and treats him accordingly.”

Nine years into the occupation the Japanese were dumbfounded as “weak” and “cowardly” Koreans initiated a highly-coordinated, non-violent independence movement throughout the peninsula. Many aspects of the Samil Movement are noteworthy. Resentment of Japanese treatment had fomented for years prior to March of 1919. Organizers had sought an opportunity to covertly initiate the movement for some time. They seized upon the recent death of King Kojong to disguise organizing efforts as funeral preparations.

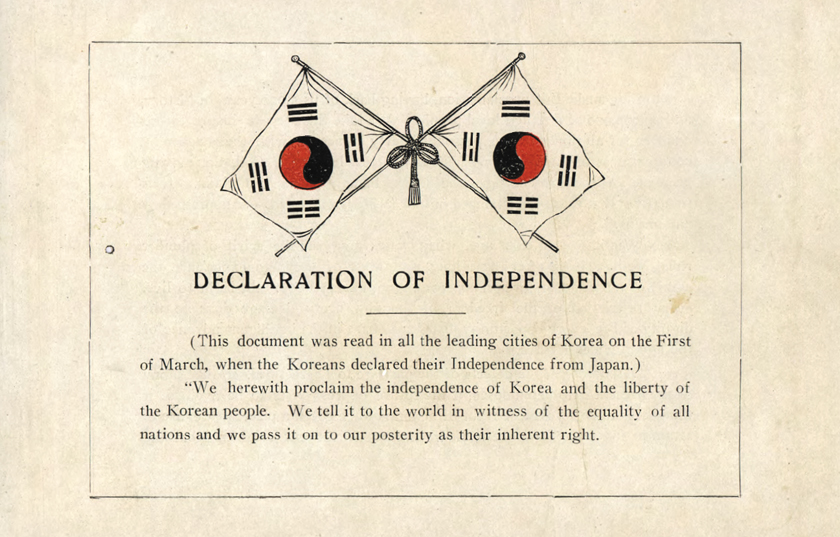

Also noteworthy is that the document, distributed nationwide on March 1, 1919 was modeled after the Declaration of Independence, which sparked the American Revolution 143 years earlier and freed colonial America from Britain. Doubtless, colonial Korea longed for a similar end to Japanese tyranny. The passage in the Korean Declaration “We shall safeguard our inherent right to freedom and enjoy a life of prosperity…” echoed the U.S. Declaration statement “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

The Korean Declaration, signed by 33 eminent religious leaders, was read publicly, while copies were distributed nationwide. After the reading, the signers had lunch and then turned themselves into the Japanese authorities in Seoul.

The Samil Movement was substantially inspired by the principle of “self-determination,” articulated by President Woodrow Wilson in his “14 points” speech before Congress in January 1918. Wilson’s hope for the post-World War I world resonated with the besieged Koreans. Koreans in exile sent envoys to the 1919 Paris Peace Treaty assembly seeking American support. Predictably, however, although Americans may have sided with Korea philosophically, Japanese pressure kept Wilson from receiving the Koreans.

Nonetheless the Koreans took Wilsonian “self-determination” to heart and shared his aspiration in their declaration:

We claim independence in the interest of the eternal and free development of our people and in accordance with the great movement for world reform based upon the awakening conscience of mankind. This is the clear command of heaven, the course of our times, and a legitimate manifestation of the right of all nations to coexist and live in harmony. Behold! A new world is before our eyes. The days of force are gone, and the days of morality are here. The spirit of humanity, nurtured throughout the past century, has begun casting its rays of new civilization upon human history.

The most exceptional dimension of the Samil Movement is its ethical foundation. Remarkably, the Korean people responded to relentless Japanese abuse, property misappropriation and cruelty with non-violent civil disobedience. After reading the Declaration, its 33 signers turned themselves into the Japanese authorities willingly and without protest. The document itself had a non-accusatory tone:

We do not intend to accuse Japan of infidelity for its violation of various solemn treaty obligations since the Treaty of Amity of 1876. Japan’s scholars and officials, indulging in a conqueror’s exuberance, have denigrated the accomplishments of our ancestors and treated our civilized people like barbarians. Despite their disregard for the ancient origins of our society and the brilliant spirit of our people, we shall not blame Japan; we must first blame ourselves before finding fault with others. Because of the urgent need for remedies for the problems of today, we cannot afford the time for recriminations over past wrongs.

Its authors concluded the Korean Declaration of Independence with the following charge to the Korean people, and open pledge to the Japanese interlopers: “All our actions should scrupulously uphold public order, and our demands and our attitudes must be honorable and upright.”

Koreans chose nonviolence as the basis for the independence movement for two key reasons. First, Japanese troops with modern weapons were stationed throughout the country. Armed revolt would have been futile and suicidal. Second, the Samil Movement’s non-violent ideology was inspired by Christian precepts (nine signers were Methodist, seven were other Protestants, two were Buddhist and 15 were from the Ch’ondogyo sect, which combines elements of indigenous religions and Catholicism) and Mahatma Gandhi’s then-ongoing non-violent struggle against Britain in India.

Korea’s doctrine of nonviolence in the face of Japanese oppression demonstrated the kind of enlightenment observed in the U.S. Civil Rights Movement, inspired and led by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. more than four decades later. King described the wisdom and rectitude of this strategy as follows: “Nonviolence is a powerful and just weapon. Indeed, it is a weapon unique in history, which cuts without wounding and ennobles the man who wields it.”

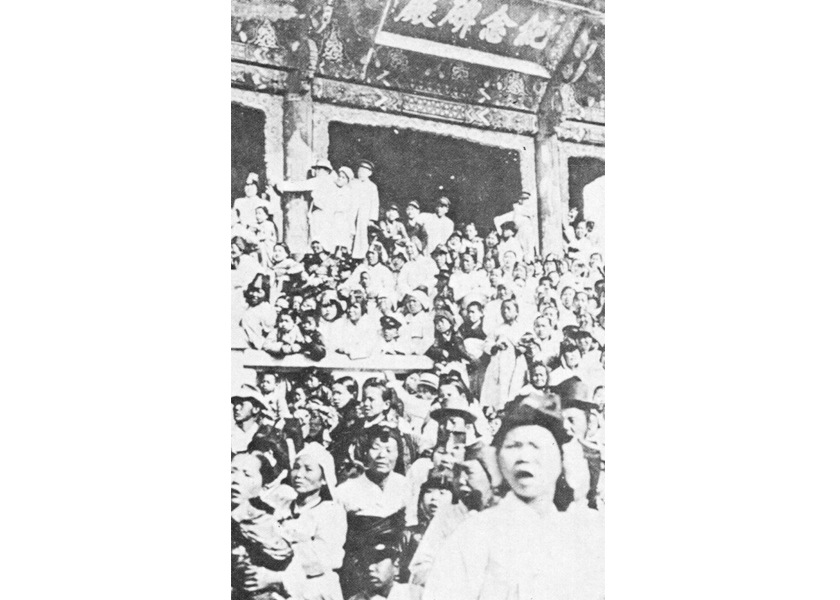

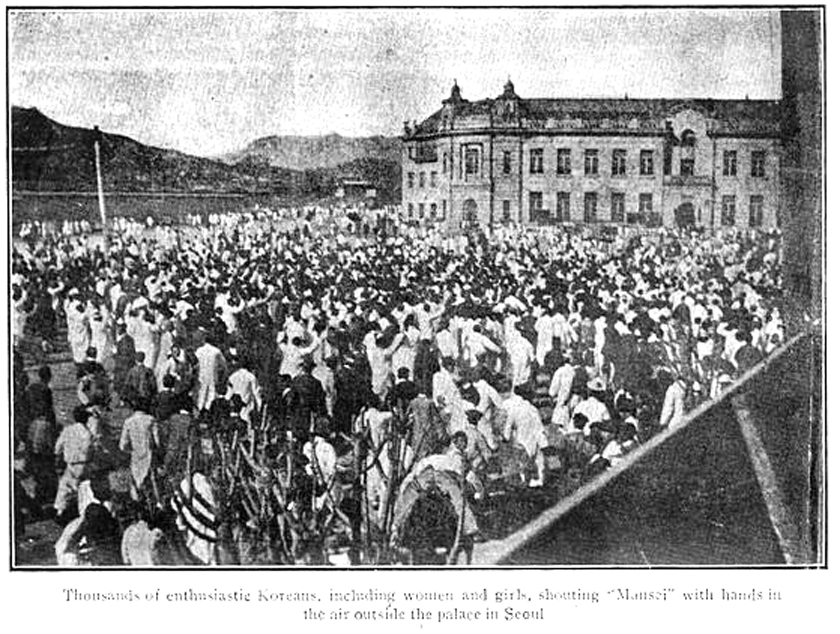

The March 1 Declaration of 1919 was intended to appeal to the conscience of the Japanese. It inspired spontaneous non-violent rallies, parades and demonstrations across the country on March 1 and for about six weeks thereafter. Protests included nonviolent raids of post offices, police stations, and various Japanese agencies. Protest participants included peasants, trades people, housewives, intellectuals, religious leaders and politicians. School children had not returned to class by March 5 and sporadic boycotts were ultimately unsuccessful. By mid-April, more than 1,500 protests had taken place in 300 cities, involving more than two million civilians (10 percent of the population).

Japanese reprisals were swift, violent: Protesters were met with torture and often death. They were herded into churches and schools, set ablaze while gunfire prevented escape. Over 7,500 people were killed and over 46,000 arrested. A principal outcome of the Samil Movement was to alert the Japanese that, although subjugated, Koreans were anything but compliant, passive or weak-willed. The movement elicited from the Japanese grudging respect for, and a new-found fear of, the people they held captive.

Tragically, though unsurprisingly, the Samil Movement did not result in Korea’s independence. Liberation would not come for 26 more agonizing years. Meanwhile, brutality, exploitation and systematic dismantling of Korean identity continued. In light of this, one might ask why March 1 is a national holiday in South Korea.

Aside from unbridled patriotism shown by Koreans, the spirit of the Samil Movement was notable and unique. It showed the world how, in the face of injustice, brutality and oppression, Koreans, who were still emerging from centuries of feudalism, chose the ethically sophisticated and ideologically precocious strategy of nonviolence in their pursuit of independence. In this strategy, Koreans created a rare, enlightened moral legacy uniquely bequeathed to future generations. African Americans take immense pride in the non-violent nature of the Civil Rights Movement of the ‘60s, and justifiably so. Korean Americans can take similar pride and guidance from the example set by our forebears a century ago.

The Samil Movement also serves as a painful reference point from which Korea’s progress comes into stark focus. A century ago, what remained of the Hermit Kingdom faced an uncertain and precarious future. Korea was to suffer a total of 36 years of Japanese occupation, and three years of civil war. In terms of national wealth or assets, what little the Japanese had not absconded with by 1945 was largely destroyed by the end of the Korean War in 1953.

Unlike Germany and Japan, post-World War II Korea had no industrial tradition or base on which to rebuild. Korea started from scratch —- with no Marshall Plan to rely on. Yet supreme effort, sacrifice, and an indomitable (and intractably stubborn) spirit propelled Korea from non-existence (as colony of Japan) to one of the largest national economies in the world today. The Korean people overcame untold adversity, mitigated the fatalism of han, and in the process, created a legacy of fortitude and resilience from which future generations can draw inspiration and strength.

Author’s note: My parents came from Korea to the U.S. in 1949. I was born in Minnesota in 1956 and grew up in the Midwest, and much of my adult life has been spent trying to understand my identity as a Korean American. I believe the Mansei Movement was one of Korea’s finest hours and is a cause for immense pride. It is also a reference point that casts modern Korea’s achievements in sharper relief.

Girls ruled (in 1919): How the engine of the Independence Movement was powered by teenage girls | By Cho-lee Yeoul

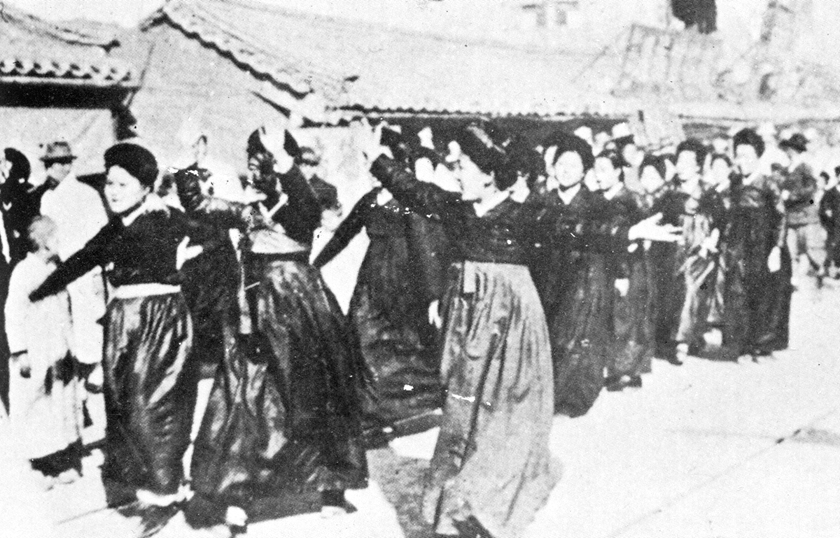

It is not very difficult to read women’s independence as a vital part of the March 1st Movement. A foreign journalist, Fredrick Arthur McKenzie, who was at the historical scene captured women’s leading role in the March 1st Movement, when he wrote in 1920:

The most extraordinary feature of the uprising of the Korean people is the part taken in it by the girls and women. Less than 20 years ago, a man might live in Korea for years and never come in contact with a Korean woman of the better classes, never meet her on the street, never see her in the homes of his Korean friends.

Frederick Arthur McKenzie (1869~1931) was a Scottish Canadian born in Quebec, Canada. He worked as an Asia correspondent of the Daily Mail, and in that capacity was assigned to cover events in Korea. McKenzie, an excellent journalist, spread the message to the world that “the Korea-Japan Annexation” was not wanted by the Korean people. When the March 1st Movement was taking place, he also advocated that the world powers, including the U.S., should listen carefully to Korean people’s voices.

With the information he collected while covering the March 1st Movement, McKenzie published his own account, Korea’s Fight for Freedom in 1920. The book sheds light on Korean society and its independence movement from the point of view of a journalist who keenly observed and recorded events and from the point of view of a global citizen who supported world peace.

In the last chapter of the book, McKenzie criticizes world powers like the U.S., which ingratiated itself with Japan and ignored the widespread and popular independence movement of the Korean people. He warned the U.S. that if it did not restrain the expansion of Japanese imperialism, there would be a huge conflict within 30 years and the U.S. would be burdened the most by it. History bore out the accuracy of his perception when the Japanese attacked the U.S. naval installation at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, in 1941 and triggered America’s entry into the Second World War.

McKenzie’s book, in which he wrote about the March 1st Movement with objective analysis and thoughtful insight into the geopolitical circumstances of Asia and the world, points out that the role of women, especially of young women, in Korea’s Independence Movement was remarkable.

“I have lived for a week or two at a time, in the old days, in the house of a Korean man of high class, and have never once seen his wife or daughters,” he said to introduce the social milieu into which women emerged as leaders in the movement. About 20 years earlier, when McKenzie had first arrived in Korea, he could not see any women on the street or even when visiting his friend’s home. Therefore, he was indeed shocked to see women showing up in large numbers in connection with the March 1st Demonstration.

Women’s public invisibility when McKenzie first arrived was hugely influenced by Confucian culture. They were supposed to stay in the domestic sphere, while the outside world was the men’s domain. A notable change during the 20 years before the Independence Movement was the establishment of girls’ schools, which allowed girls to learn about the world outside their traditional sphere. McKenzie theorized that the introduction of Christian schools and a modern lifestyle made young women choose the new culture and led to the collapse of conventional way of living.

They rejected obedience to work for independence

In The History of Korean Women’s Movements: Focusing on the National Movement During Japanese Colonial Rule, published in 1971, the author Yo-seob Jung explains that educated Korean women of the time were against the Japanese education policy and the traditional role of women. He also notes that these women sought social awakening as well as improvement in the status of women.

“In the days of the Japanese colonial rule, the education policy towards Korean women was a preparation to make them ‘Japanized women,’” Jung writes. The ideal model proposed by the Japanese was that of the obedient women. In other words, they imposed their education policy under the guise of “developing womanly virtue and good nature,” and taught Korean women to be absolutely obedient, according to Jung. “This brought about the regression of the modern women’s education. However, educated women pursued an ideal model of women’s education further developed than that of a good wife and wise mother.”

Even though girls’ schools were founded, and higher education was provided in early 1900s Korea, women and men still strictly kept their distance from each other and girls’ mobility was limited, as they needed permission from their fathers when they wanted to go out. They were also not allowed to speak about politics and society, and they adhered to strict social rules about preserving chastity; for example, their style of clothing had to be very conservative so as not to show the body. Society was dominated by such sexual norms. Despite such social restrictions, young women, especially those in state-run schools, organized demonstrations and participated in the March 1st Movement.

In the 1996 book Study of the History of Korean Women’s Anti-Japanese Movement, author Yong-ok Park reveals that female students encouraged the crowd and bravely led the demonstrations in spite of strong suppression from the Japanese colonial oppressors.

There is a story in the book about Jawaharlal Nehru (1889-1964), who led the Indian Independence Movement against British colonial rule. When Nehru was imprisoned for the sixth time, he sent a letter to his 16-year-old daughter Indira (Indira Gandhi; 1917-1984) about Korean girls’ independence movement. “The Korea-Japan Annexation is the most tragic and horrible incident in human history. I know you will be touched once you know these young girl students played an important role in the anti-Japanese struggle.”

News stories confirm women’s contributions

It is easy to confirm that the mansei demonstrations were planned and led by women by simply reading the news stories of March 1919. The Maeil Shinbo newspaper was flooded by short news stories about the mansei demonstrations in Seoul, Pyeongyang, Gaeseong, Jinju, Mokpo and many other places.

Headlines such as “Girl students started it,” “Riots of girl students,” “Conspiracy of girl students,” “Jinju — gisaeng led the way,” and “Old Masan — there were many women” began many news stories covering the demonstrations, indicating that women led the anti-Japanese movement in every corner of Korea.

In 1980, a women’s organization, the March 1st Sisters’ Group published History of Korean Women’s Independence Movement: 60th Anniversary of the March 1st Movement to commemorate the movement’s 60th anniversary. The book documents the history of the individuals and regional groups that carried out the women’s mansei demonstrations.

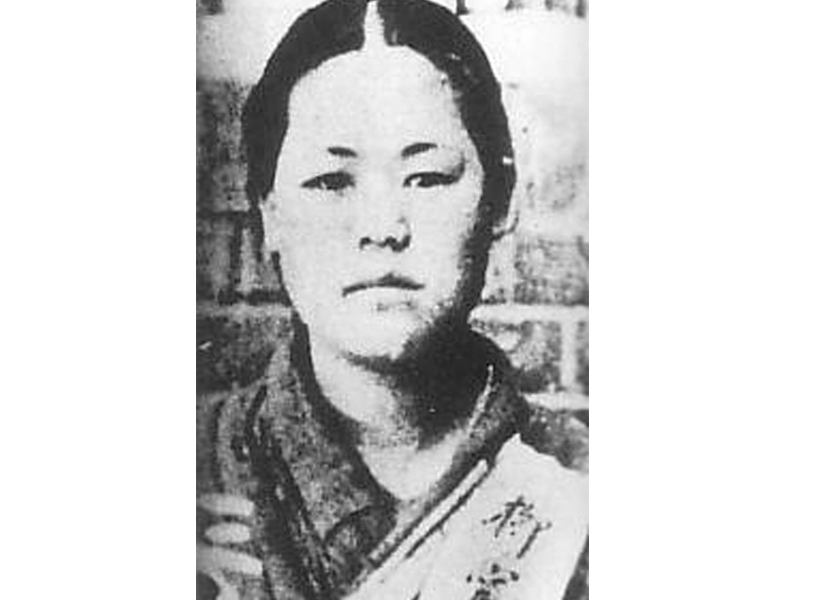

Many of the individuals who led the demonstrations were students from girls’ high schools, including the famous Gwan-sun Yu, who returned to her home town of Cheonan to organize the demonstration at Awunae Marketplace.

However, as an account of Ewha School, of one of the best-known girls’ schools, states in The 80-Year History of Ehwa, “There is no way to find out the list of participants and students who were imprisoned after being charged with a leading role.” The documentation of the names of 20 or so leaders leaves out many more nameless female students, teachers and religious adherents who organized and led the Independence Movement. The names of the women participants who were not students are not recorded anywhere, and so we can only guess how many women acted against the Japanese colonial rule and were persecuted.

No mastermind could be found

As McKenzie points out in Korea’s Fight for Freedom, “Female students were most active in Seoul. For instance, most of the people arrested in the morning of the 5th of March were girl students.”

Jung, author of The History of Korean Women’s Movement: Focusing on the National Movement During the Japanese Colonial Rule, estimated that about 10,0000 girl students participated in the demonstrations.

At that time, the Japanese police believed there was a mastermind behind the girls who were apparently organizing and conducting the mansei demonstrations. The Japanese police were desperately searching for this person, who they believed must be a man, by arresting and interrogating students. In actuality, the girl students had only their network and their strong will and belief in what they were doing.

In fact, girl students worried about their participation causing harm to their teachers and elders. They held their meetings in secret to avoid exposing their teachers and elders to their plans. Mission school students withdrew from the schools to participate in the movement to avoid causing repercussions for the missionaries.

Memoirs and testimonies collected for Modern History of Women in Korea, Vol. 1, published by March 1st Movement participant Eun-hee Choi, explain the girl students’ attitudes about the independence movement.

According to the book, 14-year-old Jeong-ae Kim of Mokpo’s Jeongmyeong Girls’ School shouted back to the questions of military police: “Why are you saying we can’t fight without being manipulated by teachers? Are you saying only grown-ups in Japan love their country but children don’t? …In Korea, even a mere child knows how to love their country. We are already grown-up ladies of 14 or 15 years old.”

The students who were arrested in the mansei demonstration in Gaeseong on March 3, 1919 were from Hosudon Girls’ High School. Yun-hui Eo, who got a two-year prison sentence, answered her interrogator “When it’s dawn, do roosters cry under the command of someone? We rise up because it’s time to become independent.”

Gwan-sun Yu, symbol of the teen girls’ campaign

The most famous young woman of the March 1 Movement is Gwan-sun Yu. In historical records, she has been called the “Nation’s Sister” and the “Flower of the Independence Movement.”

However, in addition to symbolizing the resolve of the nation to be independent, Yu also represents all of the women who led March 1st Movement. In addition to the women students, these independence fighters included many marginalized groups, such as gisaeng (entertainers), uneducated housewives and social classes thought to be low class, such as butchers’ wives.

Teen girls (and boys) have also participated in important recent non-violent struggles, such as the peaceful candlelight demonstrations in 2008 against the importation of U.S. beef suspected of containing mad cow disease, and the equally peaceful Candlelight Revolution of 2016-2017, during which South Koreans took to the streets every night for weeks to oust President Geun-hye Park and call for a new presidential election.

Gisaeng as independence fighters

In addition to the teen girl students, the gisaeng (women professional entertainers) were also key to the independence movement. In Joseon-era Korea, a society that existed until shortly before the Japanese occupation, gisaeng existed outside of women’s natural space, the home, and therefore they interacted with men and were informed about the larger society. Because their role was alternately dramatized or disparaged according to male intellectuals’ tastes in records of the times, little is known about the exact social position, role and identity of gisaeng.

In Korean Modern Women’s History, Eun-hui Choi wrote about the importance of gisaeng. Some of her information was based on the findings of Yeong-hui Choi, head of the National Institute of Korean History in the 1970s. Choi provided the following quote from a Japanese policeman:

When we were first stationed here, we never saw the Gyeongseong [old name for Seoul] courtesans drinking or dancing or playing around. The 8,000 gisaeng seemed less like courtesans than independence fighters. Sparks flew from their red lips, and they kindled the fire of independence in the hearts of the Joseon youth who came to be entertained. The 100 gisaeng houses in Gyeongseong have been reduced to criminal dens. Sometimes when we Japanese visit a gisaeng house to be entertained, their attitudes to us are as cold as ice, and they don’t speak or smile. That atmosphere makes us feel like we are ghosts, drinking in the afterworld.

Japanese police officer Chiba Ryo, stationed in Gyeonseong as Commissioner of Public Order, made this report to the Government-General in August of 1919. It indicated that gisaeng used their unique social standing to fan the flames of independence among their customers.

Gisaeng led large-scale demonstrations

Gisaeng also staged organized mansei demonstrations in Jinju, Tongyeong, Suwon, and other cities. In Haeju, there was a large-scale demonstration led by gisaeng in which the whole city took part.

People called these gisaeng who actively participated in the mansei demonstrations sasang gisaeng (or intellectual entertainers). They were considered part of the artistic class, who were educated people possessing a variety of skills. Others who worked in the gisaeng houses were known as the entertainer class.

There were mansei protests in Suwon every day, beginning March 25, 1919. The protests were begun by the Suwon gisaeng association, who marched to the front of the public hospital, where others joined in until the assembly became quite large. When Japanese military police came to arrest them, the crowd of students, merchants, and laborers protected the gisaeng, surrounded the hospital, and shouted, “Mansei!”

In Haeju, an “all-or-nothing” squad of five gisaeng, at considerable personal risk, formed a close-knit association and become independence fighters. They set a start date of April 1 at 10 a.m. to begin demonstrating. Because they could not obtain an actual copy of the Declaration of Independence that had been read on March 1, two of the members wrote it in the Korean alphabet and had it mass-printed to distribute to demonstrators.

Though mansei protests in Haeju-eup continued non-stop after March 10, the movement that began April 1 developed into a particularly large protest in which the whole city took part.

As the gisaeng, after the model of famous activist gisaengs Non-Gae and Wol-hyang Kye, took the lead and started the protest. This dedication motivated others, including housewives who came out of their houses to join the protest. People of all ages and genders ran to join the mansei fervor, and the protest led by the gisaeng grew to 3,000 people. Eun-hui Choi, in the cell next to the gisaeng in Haeju Prison, wrote, “The bruises and burns all over their bodies made it look as if snakes were coiled around them, so it was unbearable to look at them.”

Gisaeng systematically spread the movement

According to documents pertaining to gisaeng protests, far from being limited to one group or area, gisaeng involvement in the March 1st Movement happened nationwide.

Evidence of organized, gisaeng-led protests are in many newspaper articles of the day, including the Daily News (Mae-il Sinbo). Newspapers reported gisaeng wielding the Korean flag in Jinju, gathering in front of the public hospital in Suwon, and entering town offices to cry “Mansei,”, and climbing a mountain with the Korean flag.

This is documentation that shows that sasang gisaeng, through organized associations and other methods, started organized and systematic independence protests.

According to Prominent Women in History: Korea, after gathering March 18, 32 gisaeng in Jinju, including Geum-hyang Park, led the marching demonstrators on March 19. These women, carrying musical instruments and Korean flags, led protesters, and cried out “We are the proud descendants of Non-Gae. Do not forfeit the traditional pride of Jinju’s artistic gisaeng! Mansei!”

The lower-class women, the so-called butchers’ wives, took up the knives used to cut meat and joined the protest. After arresting the women, the Japanese police viciously carved the character “eda” (meaning “the lowest class,” or “butchers”) into these women’s foreheads.

In Tongyeong, intense mansei protests broke out and continued from March into April. Records presented in Prominent Women in History: Korea show that during that time, Tongyeong artistic gisaeng association members Hong-do Jeong and Guk-hui Lee sold their gold hairpins and rings to buy four rolls of cloth, which the gisaeng made into Korean flags and carried in the protests.

March 1 was a grassroots movement of people, but it is only in digging into the history that we can see how young women from all strata of society created the legacy of a peace movement that reached deep into the hearts of Korean people.

100 years on: Korean Canadian group inquires into the March 1 movement and the legacy they are living out in 2019 | By The 100 Years Team

Imagine the year 1919 in Korea. Emperor Gojong, the last emperor of the Joseon dynasty, has died. Amid rumors that he was assassinated by colonial forces, thousands of Korean people in mourning attire, straw sandals and white hanbok, arrive in Seoul to observe his funeral procession. It will be a rare instance of Korean people being allowed to gather in such numbers, and the Japanese colonizers are getting anxious.

The Korean people are unarmed. Most are malnourished; the end of the Joseon dynasty was marked by famine, and since annexation 15 years before this date, Korean rice has fed the colonizer’s people while Korean farmers have been pushed off their land. Koreans couldn’t defend themselves even if they wanted to; since 1907 it has been illegal for Korean people to own weapons.

But the Japanese are still afraid. Buoyed by a revolution in Russia and the publication of U.S. President Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points (a statement of peace principles to be used to end World War I), Korean students at the University of Tokyo had drafted a Declaration of Korean Independence just months before. Koreans had always resisted colonization, but now global support is rising for resistance to colonial violence.

In 1895, Japanese colonizers had assassinated Empress Myeongseong and desecrated her body. They cut the hair of Korean men. They drove mines into the flanks of sacred mountains. They appropriated Korean land and claimed Korean harvests while people starved. Now, as thousands of Korean people converge on the capital, colonizers prepared for violence in return.

Instead, they are invited to lunch. 33 Korean men invite reporters and Japanese officials to a popular restaurant in Seoul. There, they read the Declaration of Korean Independence, invoking a 5000-year history to call for the end of colonization. Shortly afterwards, baffled Japanese policemen receive a call from the 33, who offered themselves up for arrest. By campaigning for Korean sovereignty, they had broken Japanese colonial law.

In a coordinated move, runners disperse from the restaurant, and soon Seoul erupts in spontaneous demonstrations. Thousands of unarmed Korean children, adults and seniors throw up their hands, calling Dae han dok-rim mansei! Or “may Korea be independent for ten thousand years!” School children distribute Korean flags, stitched by hand from scrap cloth, and run door-to-door with handwritten copies of the Declaration. Shopkeepers go on strike to support demonstrators, while miners, woodcutters, entertainers (gisaeng) and farmers pour into the streets.

As Seoul fills with peaceful demonstrators, colonial police receive reports of simultaneous marches in Pyongyang, Busan, Jinnampo, Anju, Uiju, Jeongju, Seoncheon and Wonsan. Throughout the peninsula and beyond, two million people rise in coordinated demonstrations, reading the Declaration of Korean Independence and shouting Mansei!

The Japanese colonizers panic. They call in the military, and thousands of Koreans are wounded and killed as soldiers fire into crowds. The idea that Korean people had organized themselves so effectively and in total secret terrifies colonizers, who had justified their occupation by claiming that Koreans were incapable of governing themselves. Colonizers arrest thousands and brutally interrogate Koreans, looking for the foreigner who masterminded the March 1st Movement. But there was none.

The atrocities by colonial forces deepen the Korean people’s resolve. Reeling from the razing of villages, the flogging of elders and the murder of children, Korean communities rally to smuggle international witnesses out of the country. Missionaries are protected as they document “Acts of Japanese torture” in documents they carry with them to other countries. Others protect Korean people, using their British and American citizenship to advantage as they serve as human shields between the colonial military and Korean demonstrators. When they are deported, telegrams from Shanghai reach the world, and their testimony lends credence to diaspora Koreans’ calls for global solidarity and support.

Or so we’ve read. We are all young people in the Korean diaspora, part of a grassroots student team based in Vancouver, Canada organizing around the centennial of the March 1st movement. Many of us were born in Canada and never formally educated on Korean history or culture. We have all had good and bad experiences in the Korean community, and for many of us, the 100 Years Project was the first time we heard of the March 1st Movement.

For the past few months we have been learning this history, getting to know each other and reflecting on what drives us to commemorate the centennial. What does it mean to be Korean now, 100 years after 1919? What does it mean to be Korean in Canada, where colonial realities persist? What can we make of the past 100 years, and what is our vision for the next 100 years in the Korean community?

It is now January 2019. The centennial is two months away, and though we do not have clear answers, these questions have helped us solidify guiding principles as we work towards an event for intergenerational dialogue in Vancouver. After months of discussion over kimchi-making, karaoke and cheap pizza dinners, here are some of our thoughts.

We believe colonization is global

Fact: Vancouver lies on the unceded territory of three indige-nous nations: The Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh.

Colonization is real in Canada. In fact, as we write this, militarized police are converging on the lands of the Wet’suwet’en people north of Vancouver, arresting peaceful demonstrators, demolishing checkpoints and attempting to build a pipeline without consent in moves that draw eerie parallels with colonial activities in twentieth-century Korea.

As people carrying Canadian citizenship, we benefit in material ways from colonization in Canada. Korean people here have higher average life expectancies than indigenous people. We’re less likely to be apprehended as children, we’re more likely to complete school, we have access to clean drinking water… the list goes on.

As we speak with Korean people and sift through reports, it is becoming clear that what Korean people struggled against in 1919 was colonization. Wherever we are now, we are accountable to this history. In Vancouver, colonization persists and accountability involves building relationships with indigenous nations and understanding the complex histories of the land that holds us up.

We believe inter-generational trauma is real

Some days, we talk about the best joints for bingsu (a Korean frozen dessert) in the city. Other days, we discuss that one time our grandparents mentioned having Japanese names, or when we asked a haraboji how old he is and realized he would have been 10 when the Korean War started.

Being Korean seems to be marked with these moments of dissonance, when seemingly innocuous words and dates are revealed to be rooted in a grimmer reality. Though it doesn’t feel good to be faced with this history, we feel grateful to learn, rather than aching to know after it’s too late to ask. We wonder at the silence of parents and grandparents, and our own silence too: How does one ask an elder to relive and recount their trauma?

Traumatic things have happened to Korean people. It’s no secret that colonial displacement resulted in one-fifth of the Korean population being removed from the peninsula by 1945, that 2.5 million civilians were killed in the Korean War and that partition and subsequent political purges resulted in massacres long after 1953.

Whether or not we face this history, it leaks into daily life. A recent study found 80 percent of men in Korea had physically abused a girlfriend. Korea has the tenth highest suicide rate in the world. Child abuse is real in the Korean community, and stories abound of abusive disciplinary tactics that affect children for life.

In this reality, we see the face of inter-generational trauma, passed on through behaviors and coded into peoples’ DNA. 100 years down the line, it would be nice to pass on a different experience to future generations. We believe that starts with inter-generational dialogue now.

We are looking for Korean self-determination

Fewer moments make us prouder to be Korean than March 1st. In a long history of corrupt officials and world powers forcing the hand of Korean leaders, March 1, 1919 was a rare moment when Korean people looked inward and asserted their self-determination in the face of great odds.

We wonder what Korean self-determination would look like today, especially coming from the diaspora. What do we need as a community? How do we see ourselves connecting with other groups? What has been left unsaid, and how can we ensure that people are safe voicing their concerns?

We sense that other Korean people see the need for self-determination, too. When we approach them to share the 100 Years Project, we’re often met with wariness or suspicion. The most common question we are asked is, “Who’s funding you?” When we share that we are a grassroots team: “Yeah, but who’s your leader?”

Despite people’s initial response, we have been warmly supported by so many in the Korean community. After meeting us in person, people introduce us to friends and neighbors. They invite us to their homes, share their stories for hours, and send us back with gifts for our parents. Korean people have a soft spot for students, we guess. Many seem thrilled that any young Korean people anywhere would be interested in this history. We in turn are overwhelmed by the support. It is a gift to see this side of the Korean community. We feel nourished by the relationships we have made with other Korean people, and see this as the start of understanding what Korean self-determination looks like in practice.

We are looking for Korean community

For people in the 1.5 and second generations and adoptees, it can be hard to find community in the diaspora, especially without the Korean language or access to the church.

Children of the diaspora are not alone in feeling rejected and isolated. Queer Korean people, trans-Korean people, mixed Korean people, adopted Koreans, poor Korean people and many others are often marginalized within the Korean community, in opposition to the values of the March 1st Movement.

In 1919, people on the margins seriously pulled their weight in contributing to the start of the Independence Movement. Gisaeng (women entertainers who were formally government property) provided critical funds for the Independence Movement. Butchers’ wives, part of one of the lowest ranks in Korean society at the time, joined demonstrations at great risk of physical harm. Korean Christians, who had been persecuted by Korean and colonial governments, influenced the peaceful nature of demonstrations and later faced intense violence at the hands of colonial officials. March 1st was also a pivotal moment for Korean women, normalizing the role of women in the political sphere in a time when public exposure was seen as erosive to feminine morality.

The March 1st Movement re-centered Korean identity and redefined Koreans as an independent people who yearn for peace and self-determination. Now, 100 years later, we would like to carry forward these values of inclusion and community by including those who are marginalized today. This means acknowledging moments when Korean people have done harm, both within and outside the Korean community. It means addressing anti-blackness in Korean spaces and ensuring the safety of black Korean people. It means discussing the role of Korea in the Vietnam War to contextualize the impacts of military conscription on Korean families. It means expanding conventional understandings of what it means to be Korean so that people in our community are not left behind or driven away.

We are proud to inherit this history

Reading accounts of the March 1st Movement, we were struck by the brutality of colonial backlash. It was clear that Korean people participated at great personal risk, and we wanted to understand why.

We found some answers in the Red Cross Pamphlet on the March 1st Movement, published in the summer of 1919 (and accessible for free online). The pamphlet includes an English translation of the Declaration of Korean Independence. Here is, in part, what it says (boldface added by the writer) :

We make this proclamation having back of us 5000 years of history, and 20 million of a united loyal people. We take this step to insure [sic] to our children for all time to come, personal liberty in accord with the awakening consciousness of this new era…

Assuredly, if the defects of the past are to be rectified, if the agony of the present to be unloosed, if the future oppression is to be avoided, if thought is to be set free, if right of action is to be given a place, if we are to attain to any way of progress, if we are to deliver our children from the painful, shameful heritage, if we are to leave blessing and happiness intact for those who succeed us, the first of all necessary things is the clear-cut independence of our people…

May all the ancestors to the thousands and ten thousand generations aid us from within and all the force of the world aid us from without, and let the day we take hold be the day of our attainment. In this hope we go forward.

We were moved to realize that the future generations mentioned in the above excerpts include us. A hundred years ago, millions of people heard this Declaration and made the conscious decision to risk torture and arrest by marching for Korean independence. The unborn generations, people like us, were part of the reason why.

Among the 100 Years Team, we joke about being the worst descendants ever. We live far away from our ancestors’ graves, so we aren’t able to participate in many rituals. Many of us don’t speak Korean fluently, so we don’t have access to stories of what our ancestors were like. We’re hard-pressed to remember their names, never mind their biographies.

Yet two months from now, we’ll be sharing our pride and gratitude in being part of this history. In 2019, the ancestors to the thousands and ten thousand generations would include many who lived through the March 1st movement. Though the major forces of the world may have failed to bear witness to Korean people in 1919, it is comforting to think that ten thousand generations of ancestors might have. We intend to bear witness, too, by sharing our pride and gratitude at inheriting the legacy of March 1st.

So what’s happening on March 1st, 2019?

In Vancouver, the 100 Years team is organizing intergenerational dialogues at the Korean Community Centre. The intention is to bring together elders, youth and everyone in between for good food and bilingual (English and Korean) discussions on Korean identity and the significance of March 1st.

Leading up to the event, we’ll be releasing interviews with Korean Canadian people and people in Canada who are connected to the March 1st Movement. The idea is to explore what it means to be Korean and to develop a place-based understanding of Korean community.

The event and interview series will culminate in a zine of our vision for the next 100 years. We’ll be distributing the zine to Korean organizations across Canada and other places in the diaspora to share what we’ve been up to and engage in conversation.

This essay is also a call for networking. Anyone organizing a centennial event of their own (or if you would like to), we would be so grateful to get in touch. Let’s pool our resources and coordinate our organizing.