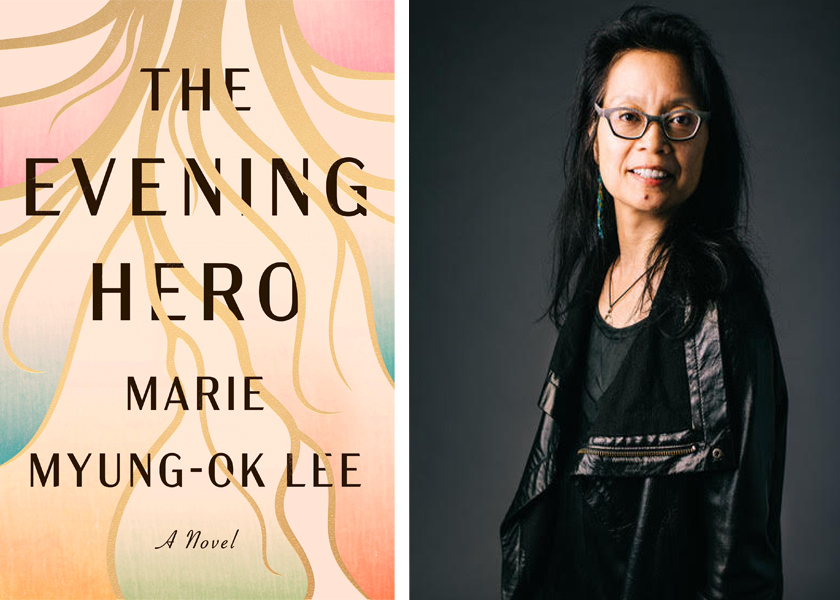

Marie Lee’s new novel honors immigrant parents’ struggle and finding one’s own authentic life | By Martha Vickery (Spring 2022)

How the immigrant generation and second generation of Korean Americans are linked by history and ethnicity, yet understand each other poorly across an immense generational divide of trauma, culture and language, is the topic of a new novel by Minnesotan Marie Myung-Ok Lee.

The title, The Evening Hero, is at once a wink at the literal meaning of the protagonist’s Korean name “Yungman,” and a foreshadowing of the choices facing her character as he enters his senior years, after surviving his youth as a war refugee and his adulthood as a driven, lonely obstetrician/gynecologist at a rural Minnesota hospital.

Lee, a professor at Columbia University, has published several young adult (YA) novels, including the acclaimed Finding My Voice, about a daughter of a Korean immigrant family growing up in a white rural Minnesota town. She also wrote the adult-level novel Somebody’s Daughter (2005), about the birth search of a Korean adoptee. Lee said she worked intermittently for 18 years on The Evening Hero, while teaching creative writing, publishing her own essays and investigative pieces for prominent newspapers and magazines, and being a mom to her medically-frail son. The life experience and the research was all fodder for her fiction.

Lee was born and brought up in Hibbing, Minnesota, and hers was the only Korean family in town at that time. Her father, William Chae-sik Lee worked as the only anesthesiologist in that city’s small general hospital. Like the doctor protagonist of her novel, her dad was a dedicated and gifted physician.

Her mother Grace Lee was educated at the elite Ewha University in Seoul, but after immigrating, spent her much of her adulthood bringing up Marie and her three siblings. Later, after moving to Minneapolis, her mother would co-found the Korean Service Center, which still exists, and still provides culturally-appropriate services to Twin Cities Korean American seniors and new Korean American immigrants of all ages.

The wife in the novel, Young-ae, is a gifted medical student who immigrates with Yungman because she sees potential in going to the U.S. and because she is pregnant by him. In the U.S., she gives up hope of a career and deals with a lot of pain and frustration due to separation from family, from culture, and from the profession she fought hard to achieve.

The author did not understand as a child or teen, or even as a young adult, how her parents’ war experiences shaped them as adults. It was well into her adulthood that her curiosity and thirst for history drove her to find out more. She knew, however, that there was only so much her parents were willing to relate.

Not satisfied with her parents’ filtered versions of their childhood under Japanese occupation in Korea and their survival of the Korean War during their youth, Lee interviewed many elder Korean immigrants over the years. The narrative derived from that research describes life in a fictional small town at the northwestern border of North and South. Due to outside political decisions, the town switched jurisdictions from North to South, and is described as a place where no one had enough to eat or ever felt safe.

There were a couple iterations of the book as it developed, Lee explained. In one, Yungman’s son Einstein was the central character. The final version has Yungman as the young, de facto male leader of the family after his father, a crop expert and botanist, is imprisoned for his politics. Sent south with his younger brother, Yungman attends Seoul National University, and through a connection he develops by working on a military base, is able to immigrate to the U.S.

For complex reasons he later regrets, Yungman decides to leave his brother behind without a word of goodbye when he heads to the U.S. with his pregnant fiancée. He feels so guilty that he never tells his wife or friends about his brother, who is his only known surviving family member. His brother finally obtains Yungman’s mailing address and repeatedly writes to him; Yungman hides the letters, not emotionally able to either read them or throw them away.

The beginning of the story coincides with the end of Yungman Kwak’s long career at the hospital in the curiously-named northern Minnesota town of Horse’s Breath. Forced to a crossroads when circumstances are imposed on him, he decides to admit the truth to his loved ones, and begins to face up to the raw reality of his life. He has the choice to either keep hoarding the debilitating secret, or redeem himself from it and free his own future.

It starts on a winter Minnesota morning, when after his feet are soaked in ice water getting from the parking lot to his office in the obstetrics department, he discovers that the case load is high for that day, and that two more of his staff had been cut for budget reasons. He is wary of the overly-cheerful patient Lorraine Maki. His guts empathetically twist for her as he watches the baby monitor, timing her contractions. He’s equally cautious about another woman who is poor and comes in often. The staff calls her a “frequent flyer,” slang for a malingerer. Yungman is not so sure.

On the same day, the hospital president calls a meeting to announce that the hospital is closing immediately, and informs the younger doctors that they have lost their pensions. The stated reason for the closure is simply lack of profit for the company that has taken over the once-independent and non-profit hospital.

Later on in the day, Yungman’s thoughts go to the allegedly malingering patient, who he believes is genuinely ill, and may need an MRI scan and a variety of other tests. With the hospital closing, he tries to create an appropriate treatment plan for her, which is tricky since the neighboring town’s hospital has also closed. He also performs an emergency surgery on a pregnant young woman – her uterus ruptures and she almost bleeds out in the ambulance. He saves both the mother and her premature baby, but has to remove the woman’s uterus.

The baby is sent 70 miles away because his rural hospital has no neo-natal intensive care unit. The mother has to be transferred – he fights on the phone with another hospital director so she won’t be charged for the ambulance transport needed to change hospitals. There is interestingly no internal dialogue about Yungman losing his job; the situation with the patients is too dire for him to think of it.

Yungman’s character is one of great empathy, to the point of feeling labor pains in his own body, and an almost superhuman know-how of what to do for patients medically. His unique skills and instincts leave almost no space for him to think of personal needs and desires. He seems laser-focused on the patient in front of him.

The very real crisis of rural hospital closings is told with a fictional and personal spin by the author. Lee wildly juxtaposes the grim health care predicament of poor pregnant women in a rural community that just lost its hospital with the shiny new world of profitable aesthetic gynecology Yungman’s son Einstein has joined. At Thanksgiving dinner, Einstein, also an OB/GYN, invites his father to try one of the “aesthetic” jobs at the new trendy clinic in the Mall of America.

The new aesthetic gynecology practice is a “start-up,” Einstein explains. It is a word Yungman is not even familiar with. Through the hapless character of Einstein, the author dives into a description of the blackly humorous and nearly-science fiction world of profit-focused medicine.

Lee is quick to say that she has researched everything she has written about, and that it is “verifiable,” — from the historical Korean War scenarios to the scary future of high-profit pseudo-medicine. Inserting herself in the medical world took some doing. At one point she got to know a fellow professor, and fan of fiction, who agreed to imbed her with a group of third-year medical students, so she could do rounds at the hospital.

After being in that group, she received an email asking her if she, “Dr. Lee,” would like to “monetize” her gynecology practice, inviting her to a conference to find out how. Lee and another conference-goer were physically ejected from that Las Vegas conference – her for being honest, him for being found out to be from a rival conference. “We kind of bonded while we were getting our asses kicked,” she joked. The rival asked her to attend his conference, coming up the same year in Arizona. That was where she really got an education.

“I had so many details that it became distracting. I did two articles, one was for the Atlantic magazine about OB/GYNs leaving primary care and doing aesthetic treatments. It was good to get it out of my system,” she said. She wrote of how medical skills are employed to create many costly services which are marketed, and sold to mostly rich people, even if the treatments or surgeries are not medically necessary.

At the Mall of America clinic, Yungman works for a few days doing laser pubic hair depilation for women, which is not a real treatment, but could be done. “Lasers are used to take off back hair and stuff like that,” Lee said. “I’m sure there will be laser pubic hair depilation very soon.”

Similarly, she wrote a piece of reportage destined for the New York Times entitled We Need to Un-Forget the Forgotten War, into which she brain-dumped some of the historical research she did for the novel. The editorial committee rejected it; so far it has not been printed. “It is a really good piece, but … if you look at what the U.S. and allies did in Korea, it is veering towards genocide,” she said. “No one wants to think about that.”

One central tension of the story is Yungman’s recollections of the past, which he confronts in the course of the story in vivid flashbacks. He was supposed to be the educated son who saves the family. Instead, he loses his family except for his one brother, whose nefarious activities fund Yungman’s medical school education. Instead of saving his brother, he abandons him. In the U.S., he continues to flee from the trauma, grief, loss and guilt. But he cannot run forever.

A second central tension between characters is the relationship between Yungman and his son Einstein, who despite being both OB/GYNs, are nothing alike, and have chosen completely different kinds of careers. Their lives are separated by trauma, culture, and even language. Einstein lives in a new gated community where the streets have storybook names, where his new house and his car with the fake gun turret on the roof have all been purchased on credit. He doesn’t have any real money coming in. His apparent wealth is all fake.

Einstein is married to a white woman who has no interest in her husband’s or parents-in-law’s culture of origin. “Please don’t speak a foreign language in the house! We don’t want Reggie to get confused!” she tells Yungman. The couple’s tween-age son seems to do nothing but play video games. When Yungman takes a stab at reacquainting himself with his grandson, he asks him about his hopes for college, but his daughter-in-law interrupts with a command not to “pressure” Reggie.

A week after the layoff, Yungman is having thoughts of “is this all there is?” He reflects that he had “never anticipated that it would end like this, his decades of accumulated experience rusting into oblivion.” Toward the end of the story, newly motivated about the future, Yungman asks Einstein if he would like to open up a clinic in Horse’s Breath so women will have access to medical care. Einstein is having none of it, not even after having his career upended by the implosion of the start-up, which was funded with private equity. When the start-up folds, Einstein is left flat broke.

The characters of Yungman and Young-ae are typical of Korean American post-war immigrants — isolated in the U.S. without any known extended family. Lee learned through her research that, like her own family, about three million families were separated by the war. Mass post-war immigration happened because 99 percent of North Korea was bombed; about 96 percent of South Korea was also bombed.

The book honors her parents and their unusual and courageous life in rural Minnesota, and even honors the scrappy people she knew in her hometown of Hibbing. It is not, however, a memoir. “My dad was different because he was super-assimilationist, and also super-Christian, so he was almost the opposite of Yungman, but at the same time, he did try to go back several times to North Korea with missionaries to bring in medical supplies.”

Her dad was always turned back at the border of China and North Korea, while the white doctors got in, Lee recalled. His last attempt was she was living in South Korea on a Fulbright scholarship. After being turned back in Beijing, he flew from Beijing to Seoul to meet her, and the two went out to a North Korean-style restaurant and had naeng myon (traditional cold noodles). He was depressed about not being able to go, she recalled. “What happened after that, of course, was that he died. Then, I applied to go to the exchange zone in Kaesong [North Korea].”

Lee was accepted as a faculty leader to accompany a student group from Brown University to North Korea. Miraculously, Lee was able to bring her mother too, her background hidden well enough in the midst of the student group. “Given that it was my dad’s dream, I felt I had to go, and had to go with my mom,” she said.

The interplay between the characters describes the chasm of understanding between Korean American wartime immigrants and the next generation. Her generational counterpart, Einstein, is written as a good example of how not to understand one’s immigrant parents. In fact, he seems incapable of seeing anyone else’s point of view.

However, many second-generation kids, particularly those of post-war immigrant parents, grew up in a vacuum of understanding even if they tried their best, the author explained. “People of my generation, our parents had so much war trauma, then came here and had so much immigration trauma,” she said. Lee said she has compared notes with other second generation colleagues, particularly a group of Korean American women writers she knows. “We kids just got so much of it, particularly about our moms being depressed. …Moms have trauma that comes out all over the place. Parents flip out, like Yungman does, and we don’t understand where that is coming from.”

The story is also about aging. Yungman has no thoughts of his own interests or ambitions, not even on the day he learns that the hospital where he has worked for many years is about to close. For many years, his leisure activities have been limited to mowing the lawn once a week. The future suddenly seems big. On a whim, he writes to Doctors Without Borders, to ask if he could join a medical team. In the flurry of activity that follows, he forgets he ever wrote the letter. In the end, he gets a chance for his own “Evening Hero” dream.

Coincidentally, around the time of her book launch, Lee’s 22-year-old autistic son, who has seldom spoken, suddenly started writing full messages on his I-pad, revealing his personality and thoughts for the first time. He wrote a toast to his mom that was given at the book launch, read by his dad. Parents and loved ones are enjoying the pure joy of the breakthrough. The book’s premise, that the future contains possibility and hope, was reinforced in this event.

Lee reflects on her own “Evening Hero” time to come. Despite the stress of being a working writer, she still loves it. “That’s the one thing I like about being a professor and being a writer is that you just get better as you get older. It’s not like being an athlete!”

The author gives herself some mental space to make a different “Evening Hero” decision in the future, as long as it is authentic one. After all, she reasons, great writers like Phillip Roth wrote a definitive last novel and stuck to their decision. Her hero Maxine Hong Kingston wrote that she regretted all the separation from her family required for her to put words to paper. She wanted a break from that. Anything could happen. The main Evening Hero lesson is to be open to the future.

“What can you do in your 70s?” the author said. “Should you just check out, or is there more life left in you? That’s part of why the title is Evening Hero, because he finds out he can do a lot of stuff at the end of his life. He doesn’t have to work at the Mall of America until he dies.”

The author will read from her novel The Evening Hero at an event in Stillwater on June 15. See calendar for more information.