Exhibit and book project Placed: korean adoptees reclaiming identity gets launched | By Jennifer Arndt-Johns (Fall 2020 issue)

Navigating the puzzle that is growing up as a Korean adoptee and becoming an adult Korean American is the stuff that much documentary-style art is made of, including my own. The creations of a younger generation is now emerging, one of which is the recently-launched book and exhibition entitled Placed: korean adoptees reclaiming identity.

The venue of the launch —- a St. Paul outdoor event space in September, complete with lots of fresh air, some sprinkles of rain, and masked participants —- made this enhanced book launch a 2020 event to remember. The content of Placed was a reminder, especially to other Korean adoptees, that every new generation of Korean adoptees must address the question of reclaiming identity for themselves.

The call

I was juggling through a typical Wednesday afternoon when I received a call from a decades old friend, Teqen, who like me, is adopted. He was born in Colombia. I was born in South Korea. We hadn’t been in touch for about a year, but when we reconnect, it is always because something notable is happening. This was no exception. Teqen said, “I’d like to attend a reception for an event I think you might want to check out.” He texted me the event link. I quickly perused it and replied, “Let’s go!”

The event —- Saturday, September 26

Teqen and I zipped over to St. Paul, remembering our face masks. I pulled into the parking area for Paikka, a former mattress factory converted into a modern event space. We followed the event signs for the book launch of Diana Albrecht’s Placed: korean adoptees reclaiming identity.

At the host station, the people at the desk greeted us warmly, and checked us in, while we read the now-customary signs about mandatory mask wearing and the importance of social distancing.

The venue was open and airy with high ceilings, aged brick walls and large doors opening into a narrow alley space. There was a sparse crowd in the alley, sipping cocktails while mindfully navigating the space for safe social distancing. Propped against the brick alley walls were a series of large candid color photographs of adopted Koreans in different environments, mounted and artfully lit on wood backgrounds.

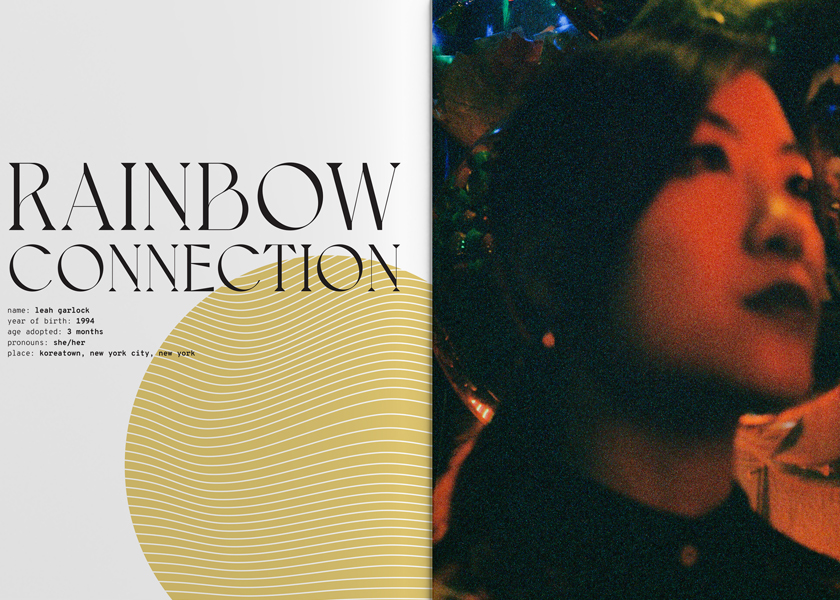

The portraits of Korean adoptees, photographed in a particular place, with auto-biographical narrative about the meaning of that place to that person, are the essence of the Placed project. At the exhibit, each portrait was accompanied by a statement extracted from their interview for the project.

Moments later, a striking young Korean American woman in a color-splashed, floor-length dress whisked by. “That’s Diana,” Teqen whispered. With an air of confidence, and a few hints of nervousness, Diana approached the microphone and introduced the singer/songwriter Mayda, who both participated in the project, and supplied the musical performance for the evening. Mayda, also a Korean adoptee —- petite, yet powerful —- stepped up to the microphone.

As the clouds loomed above us, Mayda thanked Diana for the introduction and said she would get going before the rain started. Accompanying herself on guitar, she sang her own song Lions (from her 2011 album Tusks in Furs). As if the clouds had been listening, raindrops started falling just as she finished. A team effort by the guests quickly followed to move the portraits from the alley to the warehouse.

Diana’s presentation was next, and she proclaimed “I’m really an introvert” before beginning. After that, it was as if the introvert took a back seat, as she acknowledged individuals who had helped her to make the Placed project and the event happen.

Placed consists of Diana’s story, and 10 additional stories of Korean adoptees and their significant places. Diana read an excerpt of her own story from the book. As an older observer, it was a proud milestone for me to witness a 26-year-old learning to how to live and express herself, as adopted, on her own terms.

Once the reading was over, I introduced myself to Diana, congratulated her on her accomplishment and asked her for a dialogue about her project for Korean Quarterly at a later time. She accepted and I told her I’d be in touch.

As Teqen and I departed with our Placed books in hand, the two of us reflected on how, decades later, our adoptions continue to have a defining role in our existence. We debated about how race has played an integral role in contributing to our personal trauma. We found comfort in being able to share our experiences without judgment. We reminded each other, when I dropped him off at home, how we should not let so much time pass between visits. “Let’s make it a point to get together at least once a month, okay?” I said.

When I arrived home, I tucked my son into bed, checked in with my husband, and curled up with a blanket and my new copy of Placed. As I do with nearly all things “adopted Korean,” I read the book front to back in one sitting, because it’s not that one has the luxury of discovering a project so close to one’s intimate self.

The dialogue

A week after the book launch, Diana and I conversed via Zoom. She told me she began the process of creating the book in early 2019, when she began exploring academic literature about Korean adoption history. She is quick to point out that her book is not academic reading, rather it is a creative, personal, and artistic exploration of identity. More specifically, it is an examination of the emotional impact that one’s environment (place) has upon one’s identity.

In this exploration of self, and other Korean adoptees, she questions about how one’s environment and surroundings contribute to one’s values and identity formation. She also wonders, in contrast, what kind of space or environment is needed to “unlearn” some of the inaccurate things we are taught about our adoptions and our identities. With those questions in mind, she moved forward.

The inspiration for the project, she said, came from recollection of memories of a place she once went to when she was stressed out or anxious —- a hammock in a secret spot in her ‘hood by the river. She remembered the reflections she had in that place were “easily accessible, comfortable and sacred.” This feeling, or sense, was something she wanted to explore and understand.

From start to finish, Placed was a 22-month-long process. Pretty impressive, I thought, considering that Diana juggled a real-world job, with the complications of a pandemic and an emerging racial justice movement thrown into the mix! Despite the adversity, Placed is a beautifully-executed project that explores another storied chapter in the larger Korean adoption narrative, which is still in the process of being written.

Including her own narrative, there are 11 stories of adopted Koreans, between ages 26 and 46, in locations that included Los Angeles, New York City, Minneapolis, and other Minnesota locales such as Sunfish Lake, St. Croix, and Blaine. Each story describes experiences that are unique to the individual, but also common to many adoptees’ lives. Diana accompanied each participant to the places where they feel supported, safe, validated, seen or just comfortable.

The environments include: A participant’s apartment; the streets of Brooklyn, New York; New York’s Koreatown; the candy aisle of a Los Angeles Korean grocery store; the woods; a culture camp for Korean adoptees in the Twin Cities, Camp Choson; a velodrome; the record store Cheapo Records; the Southern Theater (Minneapolis); a rooftop and one participant’s childhood bedroom. In common to each place is the importance to the participant in how that place helped them unwind, and find understanding of the many challenges an adopted person encounters as they navigate life. These places are particularly significant because adoptees are often in places where they do not feel welcomed or comfortable.

In reading Diana’s narrative, I learned that her father was also an adopted Korean, and I asked if she felt that helped or hindered her identity development. She candidly shared that her father did not help offset her “shame” around being Asian and added, “The very few conversations around Asian-ness in my family were jokes” (and not positive or constructive jokes).

After a moment, she clarified that she knows it was “super special” to him when she was adopted, because they both shared the same country of origin. She said she has compassion for what her father was incapable of sharing, acknowledging that “diversity was not likely celebrated or talked about in his era… he faced his own racism and shame that was never addressed… my dad never got what an Asian kid needed from my grandparents, so he didn’t know what I needed.” Diana’s sentiments recall the old adage that “You can’t teach what you don’t know,” and exemplify how unspoken and unaddressed emotional issues become unintended burdens that children must bear into their adulthoods.

In answer to the question “what’s next?” Diana laughed and said, “A lot of people have asked me that question.” Her goal was to meet other adopted individuals and for her project to be a catalyst for powerful growth.

“I’ve never written to this extent before and even though I have done photography for 10 years, I’ve never even printed my own photos,” she said. “I’ve learned so many things along the way making this project.” If the book can be a “minor” contribution to another individual’s personal growth, she said, that is enough to make her feel fulfilled.

Diana’s process reminds me of my younger self, I told her, when I stepped into the public eye with my documentary film about Korean adoptees Crossing Chasms 24 years ago. It struck me, reading Placed that it has been nearly 70 years since the inception of Korean adoption, yet after two or even three generations of Korean adoptees going to the U.S. and other countries, adopted people still experience the same challenges with identity and wholeness.

So I asked her —- a newer, better, version of my younger self —- “What do you feel really needs to happen to shift the paradigm? Where do we go from here?”

“It goes beyond the Korean adopted community. Any marginalized group or people always has to work so f***ing hard to create our own space,” she said, “and that in itself is such an emotional labor that is draining… we shouldn’t have to work this hard to validate our own being and our own existence. A change has to finally happen culturally in the media and culture so that groups that have been ‘othered’ don’t have to work as hard to be heard.”

Said another way, there are still systemic problems with multi-culturalism. All cultures deserve to be accepted on their own terms; not designed and limited by a white majority. Diana said she feels that minority experiences need to be “normalized” and “amplified” in the mainstream. She states, “…and our traumas don’t always have to be the main story line… as an art director, I am always aware of the story and how it is told.”

I pause for a moment, reminding myself that it is an act of self-empowerment to change the narratives of our own stories. Only then can we refuse to be “othered,” and only then can we reject the role of the victim in the greater society be free to define ourselves by our own terms. We need to reject having others realities and definitions imposed on us.

With time running out, I asked Diana about one last topic in her book that moved me. She writes about returning to her childhood bedroom. “This place represents an unconfronted animosity: Not only because of my distant relationship with my adoptive family, but my own misguided attempts to disguise the discontentment I held towards myself.” The image of Diana on the adjacent page dressed in black, juxtaposed against stark white bedroom walls and furniture, holding a Korean doll encased in a glass box, shows the contrast between the environment she once lived in, and the physical being she inhabits.

But upon returning to that same room months later, near the end of the production of the book, she writes, “…I return to this place seeking forgiveness from myself.”

Forgiveness is such a powerful, yet often neglected tenet in life. I asked Diana, “What was your process in realizing that forgiveness was necessary for your growth?”

She replied, “I am so hard on myself in every facet of my life… and I’m working on that. And some of that is because of the way I was raised, with high expectations, and I placed those expectations upon myself. I think when I was going into that moment of returning home, nervous and needing to talk to my parents, I had this vision of going home, talking to my parents and then everything would be perfect or good …and that’s not how it happened at all! I remember asking Ben [a participant in Placed], ‘Is there any resolution to this?’ and he replied, ‘Yeah, when we are six feet under.’

“I am so empathetic and understanding with others, but why can’t I do that for myself?” Diana continued, “Why can’t I give myself enough grace to pause and change my mind and not apply all this pressure on myself?”

Once she finally confronted her own place, her childhood bedroom, and decided to treat herself like just one of the project participants, she said, “once I treated myself like I treated all the participants, that’s when I was like, ‘I’m fine. It’s ok not to be ok. And it’s ok not to have all the answers. But I am doing something about it!’”

Embracing forgiveness, Diana has stepped into her place. Empowered now to take the reins of her own narrative, she is redefining a place for herself, while sharing the stories of others striving to do the same. These are the lives embodied in the Placed documentary project. It is a welcome new addition to the canon of creative work by and for the adopted Korean community.

Placed: korean adoptees reclaiming identity is available through Diana Albrecht at: diana-albrecht.com/placed