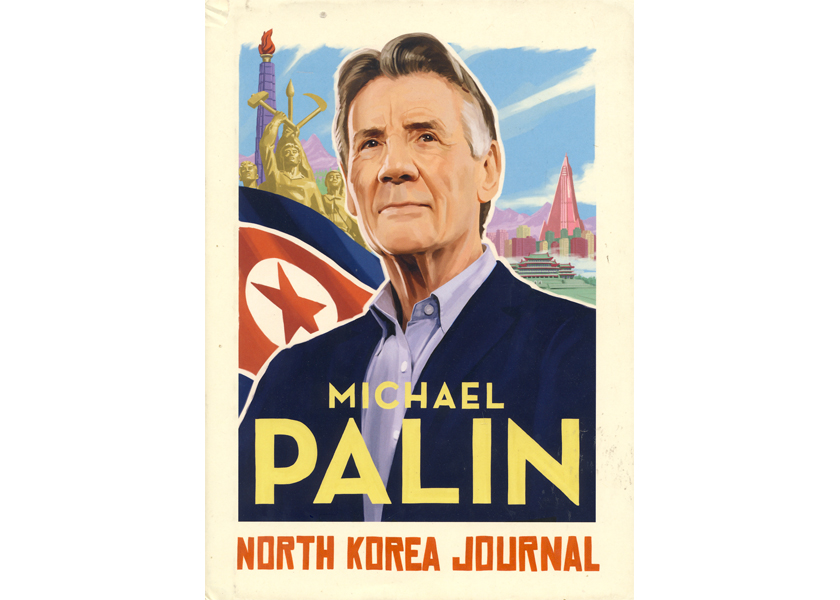

North Korea Journal ~ By Michael Palin

(Random House Canada, Toronto, 2019, ISBN #978-0-7352-7982-7}

Review by Bill Drucker (Winter 2021 issue)

In fall of 2018, the well-known British comic and travel journalist Michael Palin, formerly part of the team that created the iconic Monty Python’s Flying Circus made his way into North Korea with a four-man documentary crew to film one in a series of his off-beat travel shows, this one titled Michael Palin in North Korea. The next year, he followed up with North Korea Journal, his companion book to the film.

When a TV show promoter proposed to Palin the idea of a North Korea trip and documentary by ITN broadcasting, he was intrigued by the proposal. His wife and friends were less thrilled; they worried that this was a step too far for the adventurous traveler. The images of the young dictator Jong Eun Kim and a people subject to oppression and poverty by fearful state control were not good selling points.

Then prospects to visit North Korea opened up. North Korean tour operator Nick Bonner, who has led and facilitated trips to the DPRK for 25 years through his China-based Koryo Tours business, found a window of opportunity for Michael Palin. Other positive events moved in rapid succession in 2017 and 2018, including a diplomatic thaw between South and North that happened because of the Pyeongchang 2018 Winter Olympics, when North Korea’s second most notable person Kim’s sister Yo Jong Kim traveled to Pyeongchang, South Korea to attend the games. President Moon welcomed the dignitary; South Koreans got a glimpse of the mysterious woman.

The result was a hit two-part documentary series, and this companion book that describes some of the strangeness of North Korea, as well as some of the encounters of this funny and gregarious TV personality with North Korean people as people. The book is written sparely and illustrated with color travel photos.

With political tensions at a low, the author described how he and his and crew focused on their travel itinerary: First a flight to Beijing, and then trains across border towns Dandong and Sinuiju, with the final stop at Pyongyang Station. Before the trip, Bonner gives Palin and crew a concise set of do’s and don’ts in North Korea: No cellphone, no camera, no recorder, no this, no that.

Palin’s choice of technology for recording his travels was reduced to a blue spiral notebook and pen. His documentary crew —- director Neil Ferguson, videographer Jaimie, assistant Jake and sound engineer Doug were approved with all their gear. On the train to Pyongyang, the British travelers have a late meal of garlic shoots, pork and onions, cold Budweiser and Great Wall red wine.

In Dandong, the last Chinese stop, the crew transfer to a North Korean train. Other tourists included the Dutch, Austrians, fellow Brits, Canadians and the Chinese. Before leaving for Pyongyang, there is another extensive customs and traveler inspection. The military officials eye the crew’s cameras and equipment.

Annyonghashimnikka. Na-nun yongguksaram imnida. Hello. I am English.

Palin describes the communist state as a blend of outmoded and somewhat new architecture and infrastructure. The country is pristine, but empty. A notable site on the Pyongyang skyline is the Ryugyong Hotel, built in 1987, and known as the tallest, unoccupied building in the world. At the Pyongyang Station platform, two guides welcome Palin and crew. One is a woman in her 20s, So Hyang Li, who speaks proficient English, the other is a slightly older man, Hyon Chol Li. There is a crowd of dark-suited officials nearby. Palin notices the anxious looks of the Korean officials assigned to him and his crew. Only So Hyang can pass off a natural smile.

The group stays at the Koryo Hotel. The cameras and equipment are impounded for yet another inspection. Palin is bold enough to ask So Hyang her feelings for the Great Leaders. She is hesitant and gives a scripted answer. “They are humble and simple.” Everywhere, leaders Il Sung Kim and his successor/son Jong Il Kim are depicted as the opposite; there is one set of bronze statutes that are 72 feet tall.

Palin experiences firsthand Koreans’ respect for their elders. Approaching 75, with salt and pepper hair, he is often assisted off and on the bus by So Hyang. Life in Pyongyang is simple and orderly, with no obvious poverty. At a local Korean barbeque event, the British crew enjoy bulgogi, prawns, rice and kimchi, assorted condiments, soju and a Taedonggang brand of beer.

North Korean hospitality is notable, the author writes. Everyone is polite, if standoffish. However, Palin adds that he cannot shake off an uneasy feeling. The guided visit has been for just three days, but it seems like three weeks. The strangeness of the city and people are exhausting.

Palin makes note of the ubiquitous singing and dancing. There are outdoor loudspeakers playing music, starting early in the morning. The people seem to enjoy singing and dancing; Palin guesses it is an opportunity for self-expression.

The crew had the luxury of its own brewed Marks and Spencer coffee, supplied by Neil. The Koreans look curiously at the westerners enjoying freshly brewed coffee. The officials did not bother to enforce the hotel one-coffee rule.

At one point, Palin writes, he experiences sleeping on straw mats on a heated wooden floor. The British crew and Korean officials become accustomed to each other, even sitting down to eat meals and drink together. One day, the crew travels to the DMZ, from the North Korean side. Palin initiates the rare chance to talk politics. It is clearly a trust issue for the reticent Koreans. But Palin knows from experience, the more the people trust, the more they offer.

What is referred to as the Korean War in the west is referred to as the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War in the DPRK. At the DMZ, the crew get a tour accompanied by North Korean officer and an official entourage. As expected, they hear a scripted, propaganda speech, with language like “Americans are hell-bent on destroying the DPRK armistice machinery.” Palin cautiously says that the military stand-off must have cost the Koreans dearly. The officer agrees.

Cautiously adding to the conversation, Palin adds that he visited 22 years ago, on the southern side of the DMZ, and heard the scripted American view. Palin says that perhaps, in another 22 years, the DMZ will be a park where children from both sides can play and eat and talk together. The North Korean officers says, “I hope so too.”

On the way to Wonsan, the British crew sees truckloads of uniformed soldiers going the other way. These are North Korean military, which is assigned to domestic chores. They are assigned to work on farms, and also on construction and transportation sites. It makes sense. What group of young people are better trained, disciplined, and mobilized for such large projects?

On a co-op farm, run by Hyang Li Kim, Palin observes the workers’ sense of pride. The woman supervisor gives a tour of the farm, and then feeds the crew. Palin raises the topic of the Arduous March and the years of famine. He asks if things are better. Mrs. Kim is hesitant but replies, “Yes.” With polite insistence, she brings condiments, side dishes, soup and kimchi to the crew. She tells Palin that he must finish everything.

His British poise and western values held in check during these encounters, Palin writes in this account how he tries to understand the people’s lives under the authoritarian regime. He wonders about the extent of intellectual discourse and ideas of spirituality in the well-regulated society where religion is anathema. In both the documentary TV show and the book, the behavior and discussion of Palin and crew are strictly according to North Korean standards. Palin makes a small score at the end of the tour with a video clips of himself, acting in the 1970s British TV comedy show Monty Python’s Flying Circus. The North Koreans show polite amusement at the British humor.

The world (and now North Korea) is familiar with Monty Python alumnus, actor, writer, producer, and fearless traveler, Michael Palin. The Oxford graduate lends his warmth and wit in this engaging book which reminds us of the importance of people-to-people contact, even in a country where diplomatic relations are frosty.