Author Interview: Minnesota novelist Marie Myung-Ok Lee reprints Finding My Voice | By Martha Vickery (Winter 2021 issue)

The experience of being the only Korean, particularly the only Korean in a high school, is one that many Korean adoptee teens and many second-generation Korean American teens can relate to.

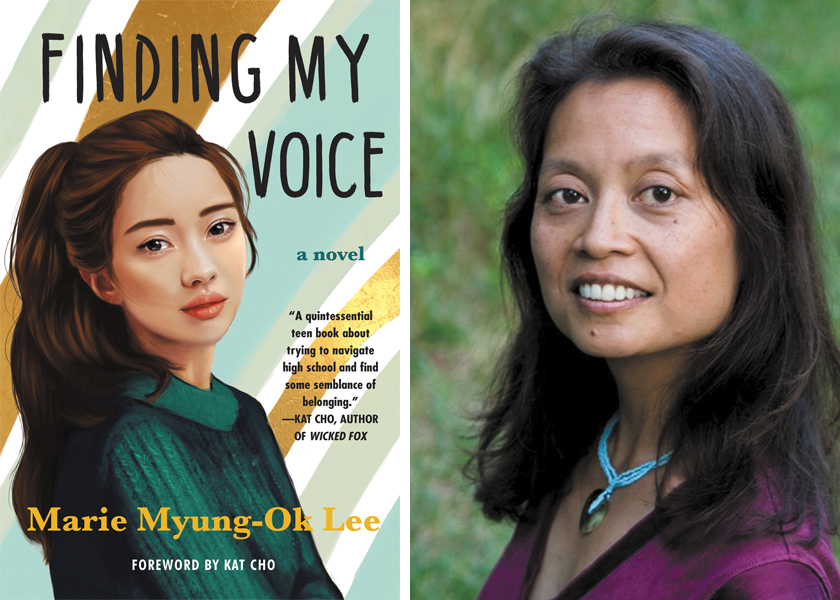

It is partly because of author and native Minnesotan Marie Myong-Ok Lee’s description of this experience that her first novel, Finding My Voice, has stood the test of time since its publication 28 years ago. It was recently reprinted (2020, Soho Press) for a new audience of young adult novel readers.

As a result, the author, now a university professor and writer-in-residence at Columbia University in New York, has been lately writing and talking about her first novel. She has written several young adult (YA) novels, including Saying Goodbye, a sequel to Finding My Voice. She has also published adult-level novels, including Somebody’s Daughter, on the topic of Korean adoptees searching for their roots.

She is launching a new (adult-level) novel in 2021, Evening Hero, which tells a story of an Korean American obstetrician in Minnesota, and his doctor son, who works at the Mall of America, and explores the timely topic of rural hospital closures. Another new novel, to be published in 2021 will be a new YA novel.

Finding My Voice, a slim and simply-worded story, packs in many key themes such as racism, anti-immigration sentiment, the culture gap between immigrant parents and children, the feeling of alienation from one’s high school peers, and the freedom and responsibility of finding one’s voice as a young adult.

Lee left her original novel untouched in the reprint, except for the addition of an Afterword by the author, in which she wrote she was surprised last year when the online news service Buzzfeed cited Finding My Voice as one of its 15 YA Novels That Have Stood the Test of Time. That prompted her agent to try marketing the book again. She was surprised again when Soho Press told her they would like to reprint the book. There was a low-key launch of the reprint, and recently NBC News interviewed her about how the book came to be in the days before speaking out against racism was even in the public consciousness.

In a recent essay in Zora, a website for writing by women of color (I Wrote About Anti-Asian Violence in 1992; Now It’s Come Full Circle), Lee wrote that she felt “conflicted” that her unchanged novel could be seen as so “relevant again.” Relevance is not necessarily positive, she writes. “Is it the overt anti-Asian racism of the Trump administration and its adherents that is driving Finding My Voice’s relevance as well?” And in a post-Trump world, “will a less overtly racist landscape make stories of anti-Asian and anti-immigrant violence irrelevant —- i.e., dismissible —- as well?”

The “normal thing,” Lee said, for a book that does OK, is to go out of print “and that’s it.” Finding My Voice has had an unusual life compared with other novels. After having a lot of trouble getting the book published originally, Lee explained,the novel did “pretty well” but went out of print due to a merger of two publishing companies. “Then an editor at Harper-Collins liked it, they picked it up and it came out again. Then, when that editor left publishing, the book went out of print again. “I would occasionally get a call, sometimes from [Korean] adoptee camps, and I would have to tell them that the book was out of print,” she recalled.

“My dream was always for it to come out again,” she said. The Buzzfeed article was the needed push; at the same time, she heard of a Twitter movement, labelled “hashtag own voices” (#ownvoices), she said, created to organize and encourage writers of color to write about their own experiences. Lee was told Finding My Voice would be an appropriate title for that collection.

Lee grew up in Hibbing, (2020 population about 16,300) in northern Minnesota, a region known as the Iron Range. It is also the hometown of Bob Dylan and the location of the world’s biggest open-pit iron mine. Like her fellow Hibbingite, who grew up Jewish in the majority white and non-Jewish town, Lee also struggled with the alienation of being in minority —- in fact, the only Asian at her high school. As an adult, she internalized it, and as an author, her experiences of growing up at that place and time have informed her writing.

The author’s isolation from other ethnically Korean and Asian people was even more complete than the characters she writes about. Beyond the ruralness and whiteness of Hibbing, there were other reasons why there were no Asian Americans around during that time.

During a period from 1924 until the Hart-Celler Act of 1965, she said, it was illegal for Asians to immigrate. “My parents were actually undocumented,” she said. “They almost got deported.” For years, she said, she did not understand why her parents chose Hibbing as a place to live, but more recently the historical context of their family story has become clearer to her. Her dad, a physician, was offered the job, and “was trying to make himself indispensable,” she said. He calculated that, if he was needed in the community, his chances were good to be allowed to stay in a town like Hibbing, where every doctor counted.

“They did get their deportation notice, actually, the day I was born,” she said. “I found it the other day. My father had hidden a lot of that stuff.” They were able to stay because a Congressman from the local district advocated for them. Her father’s strategy worked.

The environment of the story reflects a snapshot in time. Lee considered briefly, prior to the reprint, whether to update the book to a more modern time, as some younger editors recommended. She decided not to. “It is a representation of a certain time period, …and a generation of immigrants whose parents are the Korean War generation.” In a YA novel of the current time period “I would be the parent. That’s a totally different generation. I don’t want to dilute it. So, it was a very deliberate decision.” The Soho Press editor loved it as is, she added, which made the decision easier to republish without any changes.

The character Ellen’s alienation from her parents, classmates, and the culture of her small home town is the central emotional truth of the story, and relevant to all teens, particularly teens of color. From her vantage point as a university professor, Lee observes that her students are more sophisticated about racial issues than she was at that age, in part, due to social media. However, that brand of alienation “is just part of being an adolescent,” she said.

Returning to the book 28 years later, Lee noticed themes in her story related to Asian studies and history that, back when she wrote the book, were just her life. At the very beginning of the book, Ellen is dismayed that her mother adds litchi nuts to her lunch; Ellen then tosses them into the trash on the way to school. “I never even ate litchi nuts,” the author said, “and I thought to myself ‘why did I even choose that?’”

In another scene, Ellen’s boyfriend discovers kimchi in the fridge when the two are in the house alone. He tries it, likes it, and finally Ellen, who says she has never eaten any, reluctantly tries a small bite at his urging.

When Lee wrote her first novel, she was a college student in the 1980s, finding her own voice while formulating her story of identity and self. Now she realizes that her point of reference, identical to the character Ellen’s, is a reflection of her own vague ideas of Korean identity at that time. There were no other Koreans in her home town; in Minneapolis-St. Paul, there were only a few. Lee explained that the character Ellen got her last name from one other Korean American family — the Sungs — that her family would drive five hours to visit once a year in Minneapolis.

These days in the Twin Cities, there are at least four Korean-owned grocery stores specializing in Korean products, plus assorted large Asian supermarkets that sell Korean products. In Lee’s memory, there was no Korean grocery store until the late ‘70s, some years after Asians were again allowed to immigrate due to the (1965) Hart-Celler Act. The isolation from Korean American culture was almost total. The litchi nuts are symbolic of that. “That’s why, for my parents, everything that was Asian was pan-Asian,” she said.

Ellen hears her parents speaking Korean once in awhile, and longs to understand. When Lee was a child, her parents spoke to each other in English, even at home, because they did not imagine their children needing Korean or ever going back to their homeland. “The people who came after 1965, they knew that they could go back and forth, and be super-Korean,” Lee said. “For my parents, there were 20,000 Koreans total in the U.S. at the time they came here. They knew they could not go back, because they were undocumented.”

The author had to purposefully learn how to speak Korean as an adult, and eventually lived in Korea for a year with a Fulbright writing grant from which Somebody’s Daughter emerged. In 2009, almost a decade after her father died, she visited North Korea with a group of teachers and students from her university, and was able to bring her mother for a first-time visit since her immigration.

In a New York Times essay (Please Cancel Your Vacation to North Korea, March 26, 2016), after American tourist Otto Warmbier was sentenced to 15 years of hard labor for stealing a poster, Lee wrote how significant it was that they were allowed to North Korea. It happened partly because hers and her mother’s Korean American backgrounds were “obscured by our group visa.” She thought of her father, who had tried several times to return to his homeland with a medical group bringing in supplies. As the lone Korean American, he was denied entry every time.

Evening Hero has been under contract with Simon and Schuster since 2012, but the story took on a new direction after Trump was elected in 2016. After the election, the satire of the novel seemed less funny than the truth. “Satire depends on excess,” she said, and suddenly reality seemed so excessive that the idea didn’t seem to work.

Then there was the bumper sticker. Lee, who still keeps up with a Facebook group from Hibbing, saw one post that brought home to her how Trump’s elevated presence made racist talk more blatant. “It was at the time after the election when Trump says ‘we are going to nuke North Korea, and blah, blah, blah..” The bumper sticker was something to the effect of ‘Every day, 152 species go extinct, and North Koreans should be next.’”

It was like being a Korean teen in Hibbing all over again — only worse. “Imagine how that made me feel. I just felt, ‘hey, my father probably operated on you, dumbass.’ The undocumented North Korean doctor!’

After that, the novel became much more about the father character, and about what happened to him during the war. “It was the immigration novel that I did not want to write, but that is what this novel became. It became much more about rural hospital closures. The dad loses his job. He is older, and has worked at a small hospital for a really long time until the closure. And the son is working at the Mall of America at a start-up. So it goes on from there.”

The launch of the book has been delayed because of some hesitation about whether and how to do a book launch during a pandemic, but it is now going ahead.

Also going ahead, with an (at present) unknown publisher, is a new YA novel also due to be published in 2021. A quarantine year project, the new novel is still in process, and Lee is still reluctant to discuss it. It’s a big project, since the last YA novel she published was in the late ‘90s.

Theoretically, a quarantine should be a good time for a writer to create. In practice, it is difficult to summon up the energy with little outside stimulation. Enter technology. Her creative writers’ group, an informal colleagues’ get-together of people writing young adult-level novels, has been meeting on Zoom once a week. “It is the one opportunity to shut the door, not be a parent, and just be silly jerks,” she said. A recent example —- writing prompts about the Seven Deadly Sins where one writer’s creative solution was a description of the seven castaways (one for each sin) on the ‘60s TV show Gilligan’s Island.

The YA writers tend to have vivid memories of high school years. Lee confesses to not knowing much about teens “these days,” but holds on to her ability to remember what it is like to be a teen. It gets her through.

The secret? “You have to just be really immature.”

Check out Joanne Rhim Lee’s review of Finding My Voice here.