Looking back on some KQ topics at the quarter-century mark | By Martha Vickery (Spring 2022)

Today, a little over 25 years since Korean Quarterly’s founding, there are no actual statistics to show how many words were published, how many pages were read, how many copies of the newspaper were distributed through mail, at special events, and by volunteers. But for a small community group, with one paid staff, a circle of regular volunteer contributors, and other volunteer help, KQ is a textbook case of how much can be accomplished with time and perseverance — the classic example of eating the elephant one bite at a time. Undoubtedly, it could also go down in history as a newspaper business plan that was the least likely to succeed. Yet, here we are.

With some not-so-good math skills, we figured out that we have published 99 issues, including this one. Fall 1997 was the first issue of KQ, and there have been no breaks in the quarterly schedule up to now. This issue, volume 25, number two, is appearing in our 25th anniversary year.

KQ now has the capacity to be a robust online newspaper; easily updatable, more news-sensitive, global, and more budget-friendly than a paper newspaper. It won’t, however, be quite the same.

To this day, every time I open a brand new newspaper or magazine, I like the smell and texture, and the feeling I get of opening a present. For all fans of holding paper while they read, all of you browsers of bookstores, libraries and magazine racks, I feel you. We are yielding (kicking and screaming, perhaps) to the long-time trend of most readers getting their news online. We are in line with current norms, and most importantly, we will be able to keep publishing and bringing important stories, reporting, information and content to our readers.

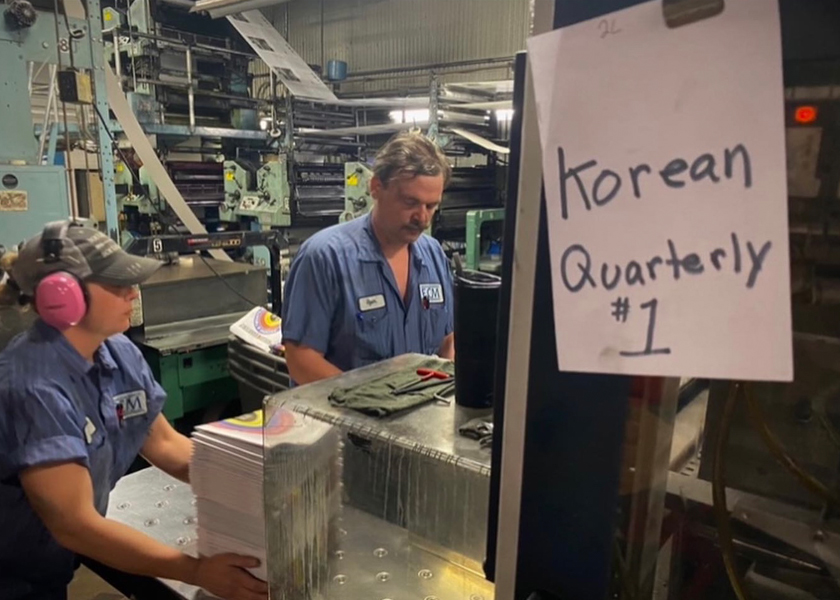

We always look forward to the weeks prior to publication — production time. This issue’s production weeks at KQ have been bittersweet. We are, however celebrating KQ’s longevity by reinventing this project in a new way, and that is a cause for celebration.

Archive at 25

Along with the online publication of KQ, which has been produced in parallel with the print edition since the fall of 2020, we have also promoted the planned KQ digital archive and fundraised to pay its design and launch (Thanks donors!) Keeping records of every story as reported is the responsibility of every news organization. It literally represents history in the making.

We at KQ feel we have an additional responsibility to the Korean American community of the Twin Cities, which helped launch our organization and has supported us. This community’s Korean American history has never been formally recorded in any archive or museum, although its history is a fascinating one. With its digital archive, KQ can make a contribution to that history.

I was very heartened to read recently that the Minnesota Historical Society (MHS) collaborated with the Twin Cities African American newspaper, the Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder to put that newspaper’s digital archives on the MHS website (the issues from 2000 on are accessible only from the Minnesota History Center). This newspaper began in 1934, and is headed up today by founder Cecil Williams’ granddaughter Tracey Williams-Dillard.

In the first editorial of what was then two newspapers, the Spokesman and the Recorder, Williams wrote that his duty was “to speak out fearlessly and unceasingly against injustice, discrimination and all imposed inequalities.” According to the Historical Society’s introduction of the archive, the two newspapers that eventually became today’s Spokesman-Recorder did a lot in addition to being the only African American news organization of its time:

The papers covered national news and issues related to race and racial discrimination and the struggle for civil rights, including the trial of the Scottsboro boys in the 1930s, Paul Robeson’s controversial statements on Communism, and the 1954 Brown v. Board U.S. Supreme Court decision. During World War II the Spokesman and the Recorder covered the actions and deaths of local Black servicemen overseas, while also reporting on racism in the military.

Seeing this archive come to life must be very meaningful for its community of readers, as a piece of Black history and identity of a people in a place, not to mention the fearless journalistic legacy of its first editor. This is just one example of what the history of a community newspaper can do, and what it can teach us about the local angle in the sweep of history.

All politics is local

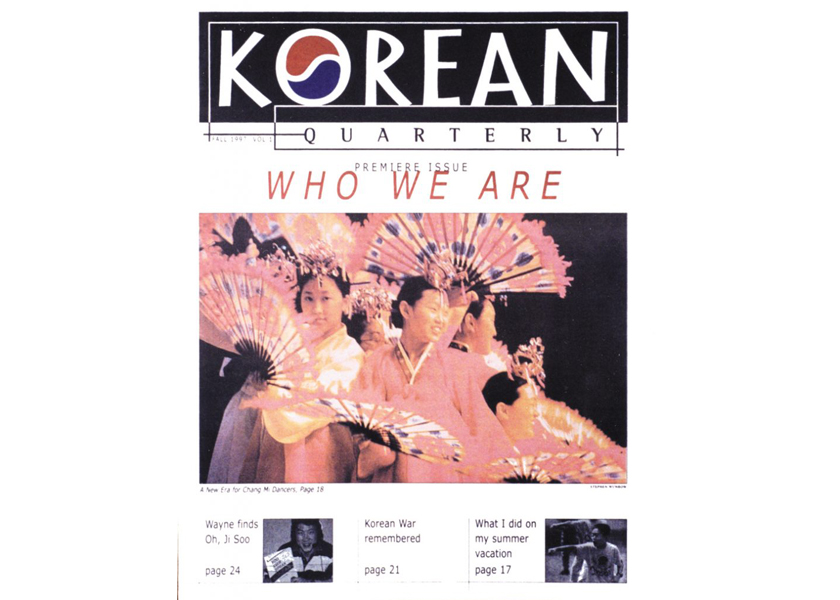

KQ’s first issue had a cover photo of dancers from the Jang-Mi dance group, what is now Jangmi Arts, in the last posture of the traditional fan dance, looking like a page from a history book, at once comfortably Korean American but also otherworldly in the ornate beauty of their traditional dress. Rereading that issue, I find all uber-local stories; we really had not collected any national/international contributors like those that wrote in KQ’s later issues. But since, as they say, all politics is local, there were a lot of local things happening that showed how national and international events reverberate locally.

For example, the fall 1997 issue detailed a story about two pastors, one local and one national denomination leader, who collaborated in a relief effort to get hundreds of tons of food aid to North Korea. It was one of many aid efforts launched by humanitarian organization during the famine that dragged on in the mid- to late-‘90s in North Korea, later referred to by North Koreans as “the Arduous March.”

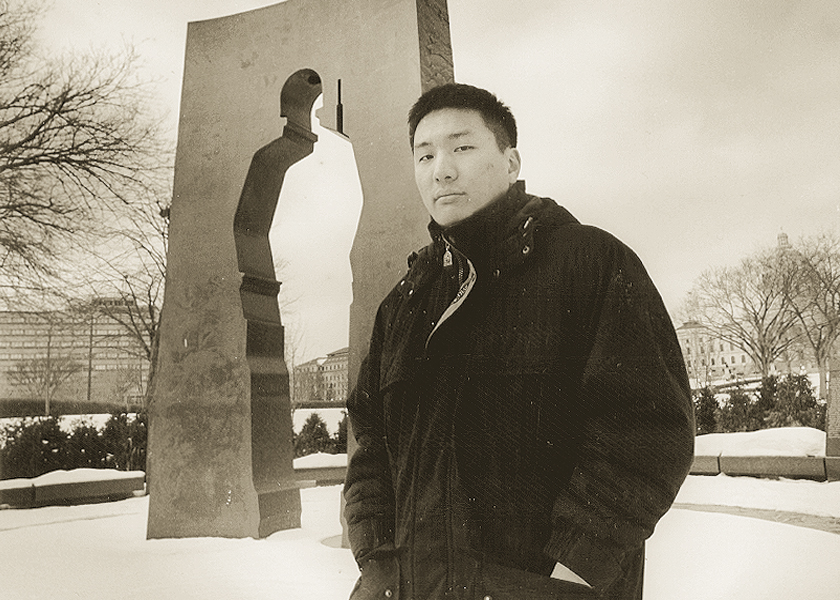

In mid- to late-1997, we were also struggling in our state’s capital city with the politics of constructing a Korean war memorial on the Capitol Mall. The Mall is where all the war memorials are located, but the idea of a memorial for the Korean War veterans was, for many reasons, a controversial one.

One of the reasons that seems the most absurd, in light of more recent advocacy for a peace treaty to formally end the Korean War, was that it was never a declared war in the U.S. for political/technical reasons, and instead was classified as a “police action.” This non-naming of wars as what they are sounds vaguely familiar, in light of Vladimir Putin’s recent prohibition of the Russian media to refer to anything going on in Ukraine as a war. Instead, it needs to be called something like a “special military operation.”

Eventually, a dedication ceremony for the yet-unfunded war memorial took place in 1997, at which Korean and American veterans told gripping eyewitness accounts of their experiences. The memorial finally came to life when a legislative appropriation paid for the rest of the costs. It is one of the most artistic memorials on the Capitol Mall today, with its lonely marching soldier who faces a ghostly soldier’s outline — a reminder of the bleakness of war, and those left behind but not forgotten.

The work-in-process

The KQ archive is not just theoretical any more, it is underway. But what will a digital archive look like, what will it be useful for, and why would readers want to look up anything in the first place?

In general, the aim is for it to be readable and accessible for both casual readers and expert researchers. Archives are good for topic and key word retrieval. Looking at all the stories written under one topic is a useful way to learn about a topic and how it was treated at a point in time. Names of anything from people to recipes, authors or even your kid’s name in a photo caption can be found through keyword searching. What KQ reported on in a specific year would also be accessible by starting at one point in time and reading on.

Specifics on how the archive will look and how it will work will be available later in 2022. The project has been years in the making, and the launch of the archive will be previewed in the online edition later this year.

The archive will be a body of work that the community will hopefully add to for years to come. It will contain the Korean American take on many books, many films, many trips to Korea, much work of many organizations, many in-depth and sometimes difficult interviews, heartfelt personal essays, poetry, photos, art.

So many thousands of pages later, are we farther along in this long and complex conversation about who Korean Americans are? We hope the archive will provide some ideas.

Seeing history as we live it, and later

We cannot know how current events will look in the context of history unless we look back on those events from a distance. A recent example of that phenomenon is how, from the perspective of 2022, the last Winter Olympics, held in Korea in 2018, takes on greater meaning.

The history of that time is more interesting in light of the Beijing Olympics of this year, at which a rigid policy of not discussing politics blew up in the host country’s face. There was so much politics not to talk about at that event, from China’s treatment of human rights to the controversial inclusion of a Russian teen skater who had a recent positive test for an illegal drug — it was all too much to shut up about and, as expected, it backfired. The games ended on a tense and uncertain note.

This is in contrast to the February 2018 Winter Olympic Games in Pyeongchang, South Korea, at which it seemed the host country front-loaded the event with politics on purpose. It was a hopeful, if short-lived thaw in the relations of the two Koreas that, in just weeks prior to the games, the two governments decided to field a joint team of North and South Korean athletes that marched under the blue banner of “One Korea” and competed together.

KQ was there, and witnessing the extraordinary events in person was an amazing thing. There was a tension in the air as news reports hinted that the two Korean leaders were actually agreeing to meet about real steps toward peace, which gave the whole event new meaning. There was an ongoing “charm offensive” as the press called it, of (truly charming) North Korean cheering squads of hundreds of young women in red-and-white outfits, in jaunty knitted hats. They sang some traditional Korean songs beautifully, and performed some fun cheer routines from their seats, to the delight of the audience.

Outside the event — well outside, on the public streets, barricaded from the Olympic venue — there were protests of supporters of the Korea joint team, flapping their blue flags. They were separated by an (unarmed) police line from the anti-North Korean camp, waving U.S. flags and South Korean flags, and bearing signs like “Pyongyang Olympics Out.” The two groups did their respective things as busses of North Korean athletes and other entourage rolled in.

This Olympics also saw the premiere Olympic appearance of Korean American Chloe Kim, who won gold in the women’s half-pipe snowboarding competition (which she followed this year with a second Olympic gold for the same event). Another exciting first was the Team Korea North-South combined Olympic women’s hockey team, with its two Korean American members, including Twin Citian (and Korean adoptee) Marissa Brandt. The men’s curling Team USA, an overwhelmingly Minnesotan group, got the gold, which also scored with Minnesotans.

Back in Minnesota, after the Olympics, Marissa Brandt and her non-Korean adoptive sister Hannah Brandt got a heroes’ welcome in Vadnais Heights, a small suburb of St. Paul. While Marissa joined Team Korea’s joint North-South team, Brandt played for Team USA which won the gold medal. Their parents Greg and Robin Brandt, every teacher and coach of the two sisters, and seemingly every family member and every kid who ever played hockey for Vadnais Heights turned out, and the rink at the recreation center next door was permanently named for the two sister Olympians.

At the time, it seemed that peace between the two Koreas might break out. In the context of the modern history of the two Koreas, the Pyeongchang Olympics, followed by the Peace Summit between North Korean leader Jong-un Kim and South Korean President Jae-In Moon in April 2018, were a brief but important thaw in the frozen relationship between the two Koreas. It showed the world what peace could look like, and that games, talks, symbolic actions, and even charm offensives can set the stage for real action toward reconciliation.

Korean Americans in pandemic times

Time is a tricky thing. History often slips away from us in our anxiety to get on to what’s next. As we emerge from the pandemic, we all want to thank the gods that this long, often boring and sometimes scary nightmare is over and we can get back to normal again. But there is a caution to this back-to-normal trend. The new normal is quite different from the old; the pandemic has scarred our collective psyche and brought about permanent change.

We need to archive this time too; Asian Americans experienced an identity moment and a time of collective grieving that grew the community locally. We, in Minnesota, were geographically and psychically in the center of a global reckoning. We are so grateful for the those who made their voices heard in KQ’s pages at this time. Some snapshots in time from issues in the immediate past give us a sense of how this time will be preserved.

It was a no-brainer to call the year 2020 “the weird year that was” in the winter 2021 issue; it was a year that started with toilet paper mania, and proceeded to the shutdown of nearly every public-facing service, from schools to restaurants, to live concerts, plays and other events. Huge swaths of working people lost their jobs. Everyone who could started working at home. It took time for society to re-tool to a pandemic economy. In the short term, Americans were shut in and scared, and Trump was referring to “the China virus” in an attempt to duck blame for his own botched response to the pandemic.

On May 25, 2020, George Floyd was murdered in Minneapolis and parts of Minneapolis went up in flames in the outbursts of grief, anger and rioting that followed

In spring 2021, when former police officer Derek Chauvin was on trial in Minneapolis, Black teenager Daunte Wright was shot to death by a white Brooklyn Center police officer during at traffic stop. KQ writer Sarah Han and her partner Kat Porter took the time to write a joint essay of how they, a Korean American woman and an African American woman, were rounded up and put in the Hennepin County lockup overnight for being Black/Asian at a night demonstration outside the Brooklyn Center police station to decry Wright’s police shooting.

Columnist Christine Heimann, who works with children through the service and mentoring organization Adoptee Bridge, wrote of how she saw Asian kids being subject to racist remarks related to COVID-19, and how throughout history there have been racist and homophobic blame for the origin of pandemics.

Before vaccines, and just when Twin Citians were dug into the loneliest quarantine days in early 2021, local Asian Americans masked up and took to the streets to speak out for and demonstrate under the banners of “Stop Asian Hate” and “Asians for Black Lives.” Thousands turned out at the Capitol and other places for demonstrations and vigils, and for numerous virtual events, following the hate crime mass shootings of eight Asian Americans, including four Korean American women, in Atlanta. There was a special demonstration in St. Paul with offerings of flowers and songs.

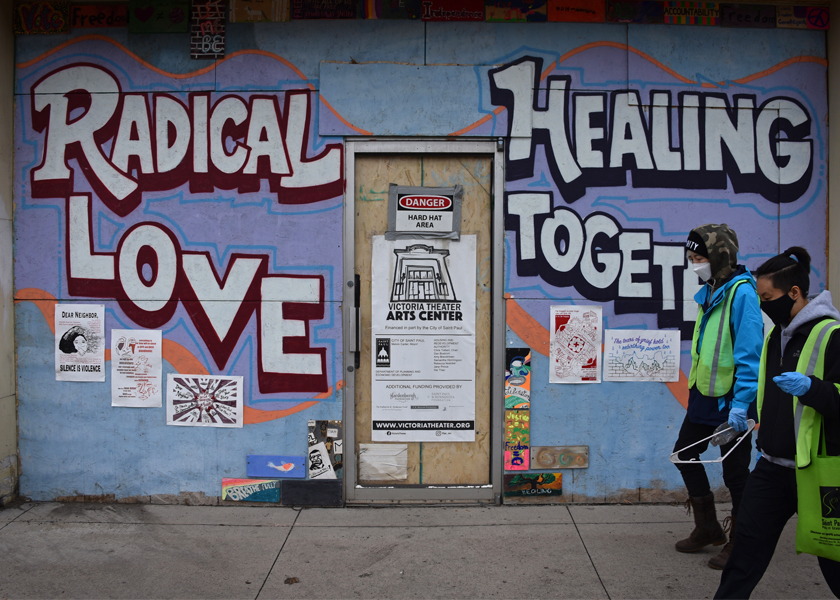

In St. Paul, a group of Asian Americans, co-led by Jennifer Amatya and Jonathan Sry, organized safety patrols to provide senior citizen escorts and other safety outreach in a group they called the Minnesota Asian Safety Squad, after there were reports of attacks nationwide on Asian people, particularly the elderly. They patrolled in the Frogtown neighborhood after the Black Lives Matter demonstrations were over, which looked very different from the old University Ave. retail area — storefronts were boarded up and decorated with BLM-related graffiti in the wake of the demonstrations and violence.

Whether we have seen a watershed reckoning in Asian American history, a step in a long battle, or just a blip on the racial justice radar screen will be decided by those who look back on it. We know intellectually that records of history are important, but in the moment, we often fail to reflect on how our moment will be seen by those who look back. An archive is a way to recognize that historical role.

In KQ’s archive from this time and other significant times when the community unified and rallied for important issues, these snapshots of history will live on through community members who committed their opinions, reportage, photos and creative work to our pages. The KQ archive, a community archive, is created and supported by a community that recognizes history and cares about the future.

The KQ Archive is made possible through a major gift from the T and W Foundation, which contributes to many causes benefitting Korean adoptees. (Thanks Thomas Park Clement and Wonsook Kim!) And to all those who contributed to KQ with their money, time and talents, you are too many to be named here, but you know who you are. Next quarter, please read on at www.koreanquarterly.org for more history in the making online!