Author Eugene Cho’s book on engaging in politics precedes his leap into the politics of hunger | Author Interview by Martha Vickery (Spring 2020 issue)

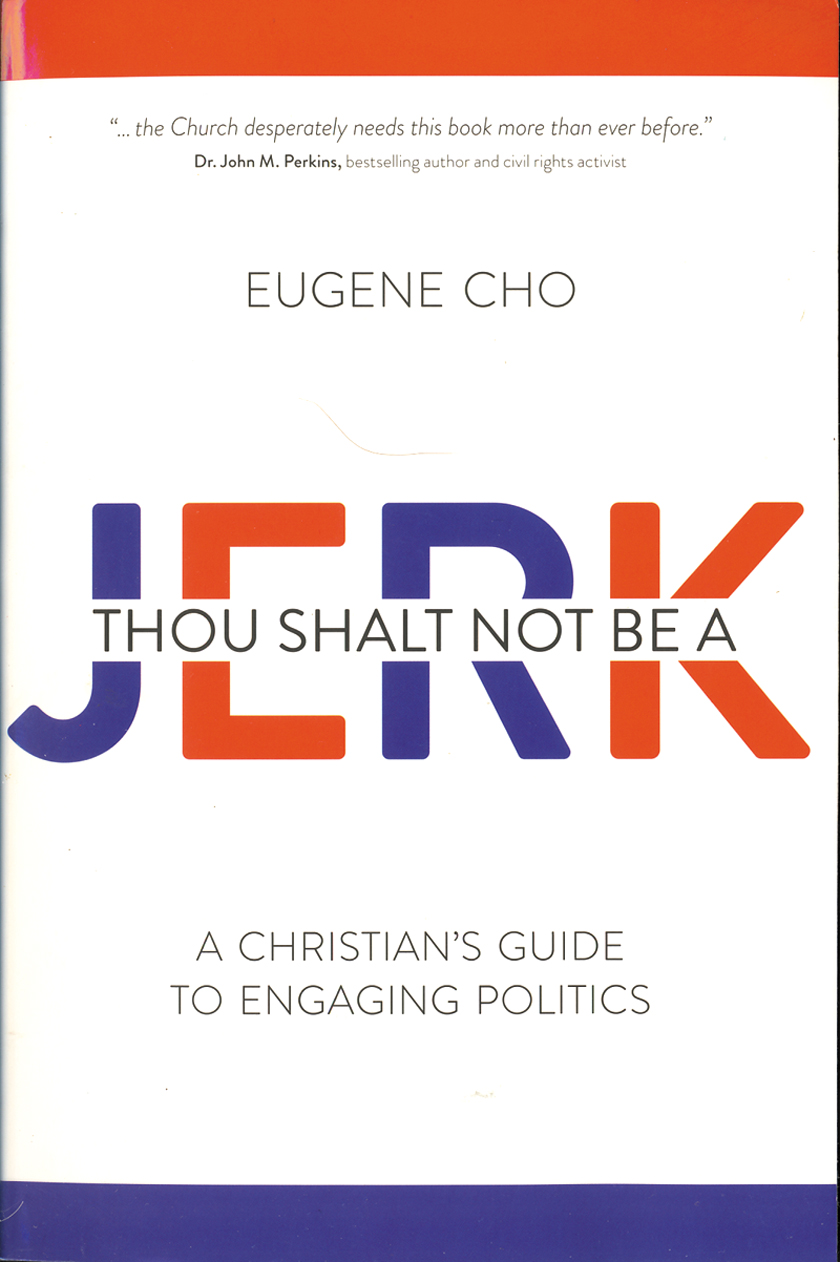

There is an interesting juxtaposition of three events in the life of pastor/author/ thought leader Eugene Cho in 2019 and early 2020. One was that he published his second book Thou Shalt Not Be a Jerk: A Christian’s Guide to Engaging Politics designed as a guide for people of faith to be able to use politics as a tool to positively impact their communities. The second was his acceptance of the presidency of Bread for the World, an advocacy organization that lobbies and influences lawmakers to craft law and policy to benefit the hungriest and most marginalized people.

The third event was the COVID-19 pandemic, which has profoundly impacted all of our lives. However, for Cho, it means that he is joining one of the largest hunger advocacy organizations at a time when the number of critically hungry people is projected to double in the months after he takes office in July.

Before this big step, Cho and his wife Minhee founded two organizations: Quest Church, a Seattle church that birthed various on-the-ground humanitarian programs, including Bridge Center, a respite and referral organization and drop-in center for the homeless; and, in 2009, One Day’s Wages, an organization that sponsors hunger relief, education and community development programs in several countries. He was senior pastor at Quest church from its founding in 2001 until 2018.

In his 2014 book Overrated (subtitled Are We More in Love with Changing the World Than Actually Changing the World?) Cho, a Korean American who immigrated at age six, describes the bumpy spiritual and financial journey of he and his wife Minhee as they pledged a whole year’s wages to launch the organization; donors are asked to pledge a day’s wages as a symbol of their commitment to the mission. He describes it as a “confessional” of his own path to how to organize for justice, even if such efforts are imperfect, or the way is unclear, or if best intentions miserably fail.

The 2020 Thou Shalt Not Be A Jerk offers 10 commandments for Christians to engage in politics with commitment to a greater good, and offers guidance, cautions, and models of how to do it. The lessons of the books are those Cho has gained from his long experience as a pastor and non-profit founder and developer. In it, he preaches that politics is necessary; moreover, for those who want to change society, it is inescapable.

“I feel like we are at a point where politics is just pervasive,” Cho said. “It is the water cooler conversation, as we live in a 24/7 news culture.” We are in a confusing time, he observed, in which there has been “a rise in vitriolic demonizing rhetoric that has consumed our culture, and has also consumed the church, and for that reason, I wrote it.”

Some people obsess about politics, and others have abandoned it altogether. In his book, Cho writes about finding a middle ground where politics can be useful. “I try to convey to people not to abandon that conversation or engagement, because politics, even though it is a scary word, it’s a very simple word that speaks about governance, and about what a healthy society should be doing.” He tells fellow Christians that the reason politics matters is “because it informs policies that ultimately impact people, and it’s a way for us to love our neighbors.”

The book is also a challenge to Christians to “be more thoughtful, to not go to bed with political parties, to rise above tribalism, and …I want to make sure I am not engaged in what I label in the book as “cultural Christianity.” His term refers to a brand of hypocrisy through which some use the label of Christianity to describe themselves while they are, in fact “depending on our power and privilege, but not following the light of Jesus Christ.”

Cho is equanimous in his assessment of the U.S.’s two political parties, and walks a careful line in saying that Christianity is not relegated to any one political party. However, he also explains that it doesn’t mean that having strong political or moral opinions is to be avoided. We should be able to give our opinion, and at the same time “not dehumanize those we disagree with,” he explained.

Cho uses some famous and not-so-famous examples of people changing history by voicing and acting on their strong convictions, including Gwan-Sun Yun, a Korean independence movement leader, who as a teenager in 1919 led other teen leaders, mostly girls, to rise up against the brutal Japanese military colonizers in Korea; her career was short and was an inspiring symbol to activists of the time. She eventually died in prison.

He also discusses Mamie Till-Mobley, the mother of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old from Chicago, who while visiting Mississippi, was falsely accused of flirting with a white woman, and was kidnapped, beaten, then shot in the head by white men, and his body thrown into a river. At his funeral, Mobley-Till insisted that her son’s body be displayed in an open casket, and hundreds came to view Till’s body; the event helped to plant the seeds of the U.S. Civil Rights movement. Mobley-Till was an outspoken activist for civil rights after that, always expressing her determination that her son’s brutal death should not be in vain.

It is a challenging place to be, speaking out your truth when it is much easier to shut up. Cho replied to a tweet by Donald Trump with the following on March 16:

Mr. President: This is not acceptable. Calling it the “Chinese virus” only instigates blame, racism, and hatred against Asians —- here and abroad. We need leadership that speaks clearly against racism; Leadership that brings the nation and world together. Not further divides.

In a follow-up interview with the Washington Post, Cho said that he knows three Asian American people in Seattle who have been victimized in incidents in recent weeks that he thinks were racist scapegoating tied to the coronavirus. “The response I got online was just incredible,” Cho said, and critics included people familiar with his book telling him “Well you’re being a jerk now,” he added.

“Just because we want to be civil and respectful and empathetic, doesn’t mean we need to be timid about calling down what we believe to be unjust. It is important for us to still be able to speak truth to power,” he said. He knows some readers will view him as “being soft by being in the middle,” he said. “But just because I am speaking from the middle does not mean I am not encouraging people to have strong convictions and views. But simultaneously, I am not going to vilify and demonize other people in that process.”

The instant communication technology of today presents a moral hazard in that “we can all be armchair pundits,” he said. While stating one’s opinion on line can be important, “if we reduce our civic engagement to just what we type, or to just reduce it to one vote every two or four years, then I would say that we’re part of the problem. That there’s something about loving our neighbors that goes beyond our one vote.”

There are also hazards in discerning what’s true and what’s false. Cho discusses discernment as a key skill for political engagement in the section on his seventh new commandment “Thou shalt not lie, get played, or be manipulated.” He explains the tendency of some political messages, especially through the filter of social media, to mislead, lie to, and manipulate people, and persuade them to distribute the untrue messages. Political messages intended to mislead depend on the reader’s sense of outrage in wanting to share the information immediately.

He tells a story of seeing the video of students from Covington High School wearing “Make America Great Again” hats smiling in a seemingly mocking way as a Native American elder drums in front of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC. There was more to the story than what the video offered, and Cho relates how he later apologized to the students, and to his more than 50,000 followers for misleading them.

“A temptation in our culture is the need to debate and comment on every single event,” Cho writes, about that unfortunate sharing of the video. “Sometimes wisdom is evident in silence. Sometimes, silence is necessary for sanity. It’s OK. Let someone else win the internet.”

He calls his own attempts at founding Quest Church in 2001, and the aid organization One Day’s Wages, and, starting in July, leading Bread for the World as “imperfect attempts by one human being trying to live out my values, my convictions, ultimately to live out my faith as a follower of Jesus.”

His first book Overrated talks about the idea of not being more in love with the idea of changing the world than in actually changing the world, in other words, that sincere but imperfect attempts are not a bad thing. In fact, they may be the only thing we humans can do to move the needle a bit toward justice.

Cho will be working remotely from Seattle as the president of Bread for the World. He has asked for an additional year to transition to living in Washington, DC. For the last five weeks, he has been doing preliminary training, meetings with staff, and other “onboarding and orientation” activities from home, he said. “It was never in my imagination to be working in DC,” he admitted.

Cho is transitioning into a high-profile leadership role at a time of crisis. Because of the organization’s size and complexity, and due to the United Nations World Food Programme predictions that COVID-19 related causes will cause extreme hunger to double during 2020, there has been a huge amount to absorb, Cho said. “It has probably been the five most intense weeks that I can recall. I feel like I’m drinking from a fire hydrant, and it just hasn’t stopped.”

Because of coronavirus effects on many national economies, he said, “the issues of hunger and poverty and vulnerability have been deeply, deeply exposed, in our neighborhoods and our nation, and certainly around the world.”

Recent images of supply and demand failures in the U.S. have been disturbing, he said. “You know there is something wrong when there are lines and lines of cars waiting to get one or two bags of groceries, in what is supposed to be the richest country in the world. And then you see these images of farmers draining their milk. There is something wrong with the system,” he said, but it is also a problem that defies a quick fix.

To fix hunger in the U.S. and abroad, there is a complicated mesh of interrelated issues at play. More funding could go to direct relief organizations and food banks, higher wages would help, as would sustaining people’s jobs during the downturn, and providing health care. In subsequent phases of the stimulus bill, Cho said, Bread for the World has been pushing for an increase in SNAP benefits [the Supplemental Nutritional Aid Program, formerly food stamps], as a source of immediate relief. It is basic that knowing where one’s food is coming from relieves a lot of anxiety for families on the margins.

Cho said he has made 80 percent of his income in the recent past as a speaker. That revenue stream is gone now. “Once that initial phase of complaining and whining had faded away, I kind of realized ‘I don’t have to worry about my next meal,’” he said. “I don’t even have to worry about a few months of mortgage payments because I have a safety net. The reality is that even in our country, there are those who have no safety net. There are stories of people at risk of dying because they don’t have access to food, with so many nations in lockdown right now.”

The idea of leading this complex organization at this moment of global crisis “is overwhelming,” he said. “The task will be enormous. It was enormous to begin with two months ago when I made the decision to accept their offer. I feel incredibly overwhelmed and disoriented, but what I have to realize is that I’m not the first and won’t be the last person who is engaged in this. And that it’s not solely my responsibility.”

Bread for the World has a practice of making members into activists, which for Cho is like having companions for a difficult journey. There is also an experienced staff, and regional coordinators around the country. Individual members “give to support our work, write letters to our lawmakers and local leaders, and join us during summits where we host people around the country,” he said. This year the summit will be replaced by virtual events, he added.

There’s a tension and juxtaposition on how humans react to crisis, Cho said. There are a range of reactions, from shoppers hoarding toilet paper to health care workers working brutally long shifts in conditions that could expose them to the virus. “As human beings, we have to give ourselves room to wrestle with our fear, our grief, our lament, our inclination to think of ourselves, and I think the best of humanity is not the superhero complex, where we jump off the building,” he said. Rather, it’s the wrestling itself that draws us out of crisis. Getting to a point of equilibrium requires that “we realize that fear is not something we desire to be a permanent resident in our lives,” he said.

Bread for the World’s leadership expected donations to fall off when the coronavirus hit, but instead, interestingly, the opposite happened. It was an encouraging development that emerged from recent dark weeks. “I think it is just evidence of people wrestling with moral, ethical and spiritual decisions,” Cho said, “about how they want to be a part of the solution, knowing that there are so many people who are deeply impacted.”

Korean Quarterly is dedicated to producing quality non-profit independent journalism rooted in the Korean American community. Please support us by subscribing, donating, or making a purchase through our store.